THE PAPERS OF ADLAI E. STEVENSON. VOL. 4. LETS TALK SENSE TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE." 1952-1955

July 1974 CHARLES M. WILTSETHE PAPERS OF ADLAI E. STEVENSON. VOL. 4. LETS TALK SENSE TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE." 1952-1955 CHARLES M. WILTSE July 1974

WalterJohnson '37, editor. Boston: Little, Brownand Company, 974. 628 pp. $17.50.

In retrospect, prosaic events sometimes stand out as turning points that shape the course of history. Reading today this fourth volume of the papers of Adlai Stevenson, one cannot avoid the eerie feeling that 1952 was such a watershed - and that we were somehow beguiled into making the wrong choice. To reread now the speeches and correspondence of Stevenson's first campaing for the presidency is a chilling and disheartening experience. We were then so near to realizing in 20th-century idiom the best hopes and finest aspirations of the practical idealists who founded this nation; yet we opted for letting I ke do it with no questions asked. Through sheer inertia we sowed the wind, and the whirlwind is at hand.

The volume begins with Governor Stevenson's welcoming address to the Democratic National Convention which opened in Chicago on July 21. He had so far resisted all pressures - even from President Truman himself - to avow his candidacy. He wanted, he still insisted, only to succeed himself as Governor of Illinois. But a National Committee for Stevenson for President (co-chaired by the editor of these papers) was hard at work against the non-candidate's wishes, and a genuine draft, with or without his cooperation, became almost a certainty after his brief welcoming remarks. For what Democrat could resist the magnetism of a man who rested the party's claim to primacy upon its understanding of "a world in torment of transition from an age that has died to an age struggling to be born?" He was nominated on the third ballot.

The campaign thus launched is the theme of the first third of this volume, and a most extraordinary performance it was. The speeches, though drafted by many hands, all bore the inimitable Stevenson touch, both for content and for style. They were deft, light-hearted or profound as the subject dictated, always apt for the particular audience, always informed, leavening with humor the Sledgehammer blows and overlying irony and ridicule with hope and faith. For clarity, lucidity, and courage few speeches In our political history equal them. Here was a candidate who insisted on "speaking sense to the American people," who ducked no issue to avoid taking a controversial position, who was Capable of sharply reproving old and valued friends for suggesting it. Here was a man who had immense pride in his country, faith in its essential honesty, affection for its people. The temptation to quote at large is great but the reader may select almost at random for himself. Let one passage suffice here: "Win or lose," he said in September, "I will not accept the proposition that party regularity is more important than political ethics. Victory can be bought too dearly."

In defeat, Stevenson's stature rose. Praise for his campaign poured in, from those who voted against him as well as from those who gave him their support. Reluctantly he retained the mantle of party leadership and set himself, over the next four years, to revitalize the organization; to identify the issues and to outline policies. For his own education and enlightenment, he toured Asia, the Middle East, and Europe in the spring and summer of 1953, which will constitute the subject matter of the next volume. He was back in late August, working quietly and diligently with a core group that included many of his former aides. He kept in close touch with leading Democratic politicians, seeking their views, soliciting their judgments, but promising nothing - not even that he would run again. He made that announcement only in November 1955 after he had convinced himself that no viable alternative was at hand.

He continued during this period to speak out on national and international issues. Time and again, by his clear reasonableness, he forced the Eisenhower administration to follow his lead. To cite only one instance, in his radio braodcast of April 11, 1955, he gently ridiculed the thought of risking a third world war to deny to Red China hegemony over two tiny islands as near her coast as Staten Island to New York. "With the invention of the hydrogen bomb and all the frightful spawn of fission and fusion, the human race has crossed one of the great watersheds of history, and mankind stands on new territory, in uncharted lands."

As we have come to expect from its predecessors, the volume is skillfully edited, with headnotes couched in lean but illuminating prose carrying the continuity. Even more than in the earlier years, the Adlai Stevenson of 1952-1955 is required reading for all Americans, regardless of party, who believe with Stevenson that "We can chart our future clearly and wisely only when we know the path which has led to the present."

Dartmouth Professor of History, Emeritus, Mr.Wiltse is occupied in the Dartmouth CollegeLibrary as editor of the Daniel Webster Paperswith the first volume of this major scholarlywork soon to be published.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degrees

July 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureTruckin' from the Meat Bar

July 1974 By JOHN GANTZ -

Feature

FeatureThe Valedictories

July 1974 By LAN R. LAW '74, John G. Kemeny -

Feature

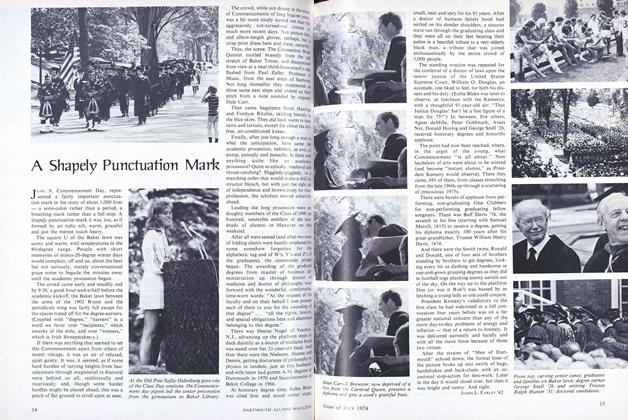

FeatureA Shapely Punctuation Mark

July 1974 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

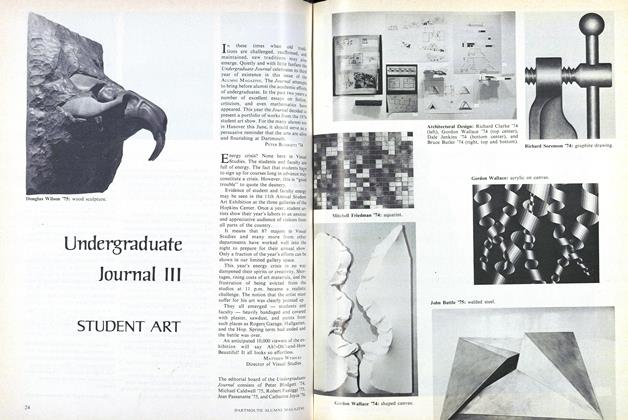

FeatureUndergraduate Journal III

July 1974 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

July 1974 By JACK DEGANGE

CHARLES M. WILTSE

-

Books

BooksJOSHUA R. GIDDINGS AND THE TACTICS OF RADICAL POLITICS.

OCTOBER 1970 By Charles M. Wiltse -

Books

BooksTHE HEALING OF A NATION.

OCTOBER 1971 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksTHE PAPERS OF ADLAI E. STEVENSON: WASHINGTON TO SPRINGFIELD. 1941- 1948.

APRIL 1973 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Article

ArticleWebster and a Small College

April 1974 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksA Strong and Hungry Spirit

June 1975 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksThe President's Secret

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Charles M. Wiltse

Books

-

Books

BooksEFFECTIVE USE OF BUSINESS CONSULTANTS.

JANUARY 1964 By ALVAR O. ELBING JR. -

Books

BooksSHAKESPEARE'S POETICS IN RELATION TO KING LEAR.

MARCH 1963 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Books

BooksHoarding or Sharing

May 1975 By DENIS G. SULLIVAN -

Books

BooksSplendor

MARCH, 1928 By H. B. Preston '05 -

Books

BooksDREAM AND THOUGHT IN THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY, 1860-1900.

January 1957 By JAMES F. CUSICK -

Books

BooksAMERICAN LABOR TODAY (Reference Shelf, Vol. 37, Number 5).

JULY 1966 By ROBERT M. MACDONALD