ByJames Brewer Stewart ’62. Cleveland andLondon: The Press of Case Western ReserveUniversity, 1970. 318 pp. $8.50.

The moral revolution that culminated in the abolition of slavery entered its political phase in the 1830’s. The “gag rale” and the proposed annexation of Texas united the anti-slavery forces in opposition. Critics of the slave trade sharpened their tone, the anti-slavery cause gained new recruits, and the South, on the defensive since the Missouri Compromise, sought salvation through internal unity. The election to Congress in 1838 of Joshua R. Giddings, militant antislavery Whig from the Western Reserve District of Ohio, did nothing to smooth the troubled waters of sectional cleavage.

Giddings allied himself with John Quincy Adams, eloquent anti-slavery leader of the House, and soon became Adams’ strong right arm. His first sight of the slave trade as it existed in the District of Columbia only con- firmed Giddings in the righteousness of his cause. His maiden speech, adroitly turned to avoid the gag, was a sharp attack on this nefarious trade, which earned for him the lasting enmity of the Southern contingent. Scarcely two years later he upheld the Creole mutineers, was censured by the House, and resigned his seat. Standing immediately for reelection, he was returned to the House by a vote approaching 20 to 1.

In this admirable biography Mr. Stewart shares with us the spiritual agony of a dedicated man, seeking always to destroy the institution he hated without also rending the Union he loved. He believed in a political rather than a revolutionary solution. He hoped beyond the limits of hope to reform the Whigs, then reluctantly joined the Free Soil movement, only to see that party too disintegrate as suddenly as it had come into existence. Opposition to the exten- sion of slavery was not enough without the cement of patronage that comes only from political victory. Although most Free Soilers returned to their original party allegiances, Giddings held firm until the new Republican party absorbed all dissident elements.

For Giddings, although he towered above most of his contemporaries in courage and singleminded devotion to a cause, his politic- al pilgrimage was marked by failure. The gag rule was repealed, but he could not block the annexation of Texas, the War with Mex- ico, the Compromise of 1850, or the Kansas- Nebraska act. Yet his achievements were solid enough in his time to win wide acclaim and at last a public office from Lincoln. He lived to see the Emancipation Proclamation but not the final victory. He died in Montreal, where he was serving as United States Consul General, in 1964.

It is altogether fitting, in this day of renewed emphasis upon civil and human rights for the Black man as well as for the White, that Joshua Giddings should find at last a biographer of skill, insight, and sympathetic understanding.

Editor of the Daniel Webster Papers, Mr.Wiltse is Professor of History, DartmouthCollgee.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryLiberating the Ph.D.

October 1970 By Robert B. Graham ’40 -

Feature

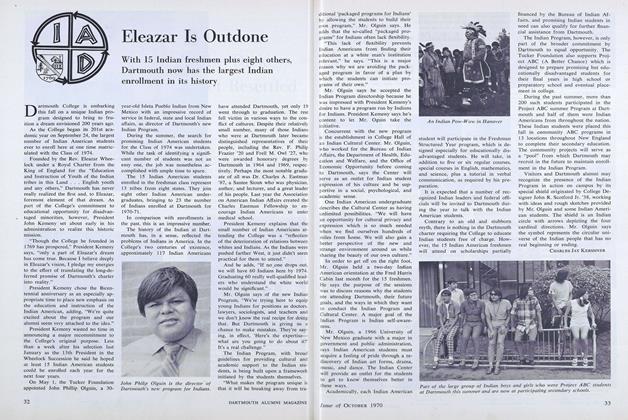

FeatureEleazar Is Outdone

October 1970 By Charles Jay Kershner -

Feature

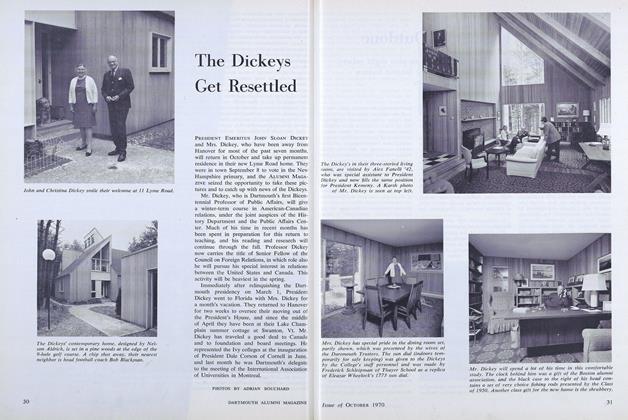

FeatureThe Dickeys Get Resettled

October 1970 -

Article

ArticleDear Mr. Cunningham . . .

October 1970 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

October 1970 By William R. Meyer -

Sports

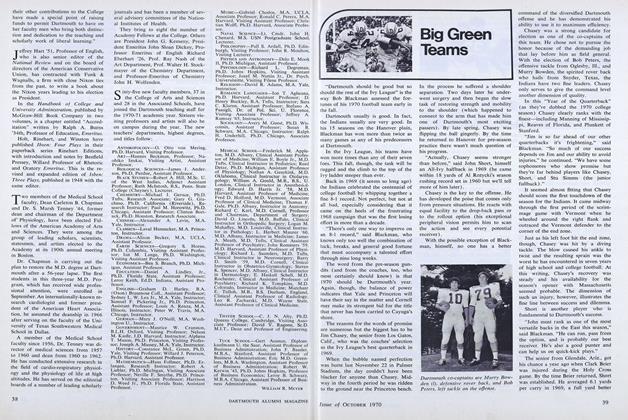

SportsBig Green Teams

October 1970 By Jack DeGange

Charles M. Wiltse

-

Books

BooksTHE HEALING OF A NATION.

OCTOBER 1971 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksTHE PAPERS OF ADLAI E. STEVENSON. VOL. 4. LETS TALK SENSE TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE." 1952-1955

July 1974 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksA Strong and Hungry Spirit

June 1975 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksTalking Sense

JAN./FEB. 1978 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksRecord Completed

March 1980 By Charles M. Wiltse -

Books

BooksThe President's Secret

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Charles M. Wiltse

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

December 1942 -

Books

BooksHANOVER, NEW HAMPSHIRE:

July 1961 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

BooksMaverick

May 1980 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Books

BooksStar-Studded Life

February 1976 By J.B. WATSON JR. -

Books

BooksTHE A. M. C. WHITE MOUNTAIN GUIDE

October 1936 By Nathaniel L. Goodrich -

Books

BooksBLACKS IN THE INDUSTRIAL WORLD: ISSUES FOR THE MANAGER.

February 1975 By ROBERT MUNRO MACDONALD