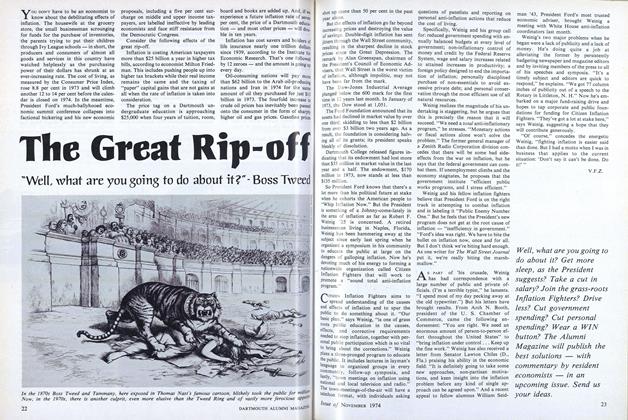

FROM all outward appearances Danny Kopec '75 seems to be the typical Dartmouth student. Intelligent and articulate, the native New Yorker has an active participation in athletics, a nine-year history of violin playing, and a new-found interest in the Kiewit Computation Center. As he likes to say, he's just "a regular guy."

But this regular guy also happens to be a Master chess player, so rated by the United States Chess Federation - one of the best up-and-coming young players in the country. He's also pretty modest about his ability. "I'm just one of the top 75 players in the country," he explains, "that's all." (There are 40,000 ranked players in the U.S.)

"People always think I'm a genius or something," says the math-psychology major. "Well, I'm no prodigy. It's just chess. Some people ski very well, others play the violin. I play chess."

Indeed he does. He learned the game when he was eight at an after-school recreation center and by the time he was 12 he was playing in tournaments. At 14 he won the New York high school cham- pionship. There have been numerous tournament titles since then, including the prestigious Greater New York Open, and high scores in others. In fact, he's just back from Louisville, Kentucky, where the Dartmouth Chess Team grabbed a seventh place at the Pan American Intercollegiate Chess Tournament among 88 schools competing. For Kopec, the tourney represented a personal victory. He won seven matches and drew one, for a phenomenal score of seven and a half of a possible eight.

In the highly competitive world of chess, Kopec's ranking currently stands at 2,270 points. It takes 2,200 points to be classified a Master and 2,400 to be recognized as a Senior Master. Kopec, who became a Master at the age of 17, is confident that he can conquer the next hurdle. "I still have a ways to go," he admits, but he thinks he can make it. "Chess requires total devotion," he says. "It demands a lot of work, concentration, and memorization." He has only advanced 70 rating points since coming to Dartmouth. To advance, a chess player must beat players with higher ratings; he loses points when he is defeated by lower-ranking players.

The problem is that there aren't any higher ranking players in the Hanover area. So while Kopec can easily lose points while playing at Dartmouth, the only way for him to advance is to enter tournaments in distant cities and such travel interferes with his school work. But he hopes to start moving again in March, when he graduates, and plans to reach the 2,350 plateau by next September.

Though Kopec claims he has the potential to be in the "top ten in the world," he has no intention of devoting his life to chess. "Chess is no way to make a living," he says. "It's a desolate life to lead. You get old and your game starts going. But you have to win to make money." Instead, he hopes to do research on the human brain by simulating intellectual processes on the computer. A B-minus average killed his ambitions to go to medical school directly after Dartmouth, but he hopes to take a Ph.D. in computer sciences instead. Though he claims to be "afraid of the computer jocks," he is currently working at Kiewit and trying to perfect - you guessed it - a Dartmouth computer chess program.

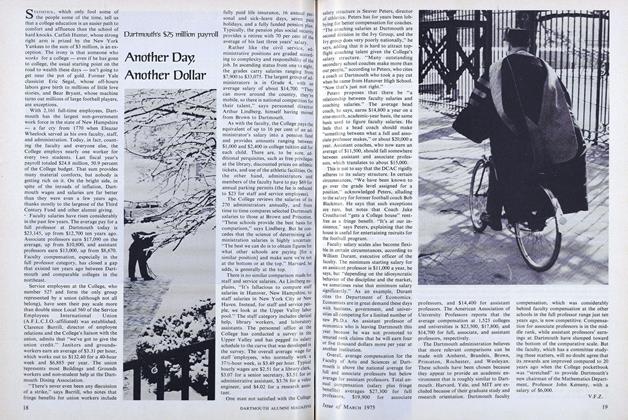

Kopec Vs. Ocipoff (C.C.N.Y.) 1974-75 Pan-American Intercollegiate With the position after 23 moves shown in the photograph above, Kopec (white) plays 24 ... QxR!! The game continues 25 ...NxQ; 26 ... NxP, B-N2; 27 ... NxR double check and white wins.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStar Birth, Star Death, and Black Holes

February 1975 By DELO E. MOOK -

Feature

FeatureHONOR: The Vanishing Principle

February 1975 By JAMES A.W.HEFFERNAN -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Rip-off

February 1975 -

Article

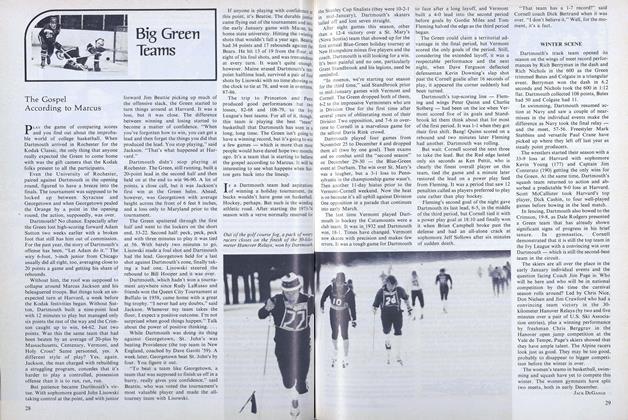

ArticleThe Gospel According to Marcus

February 1975 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

February 1975 By J.H. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

February 1975 By PAUL WOODBERRY, CHARLES S. KILNER

V.F.Z.

Features

-

Feature

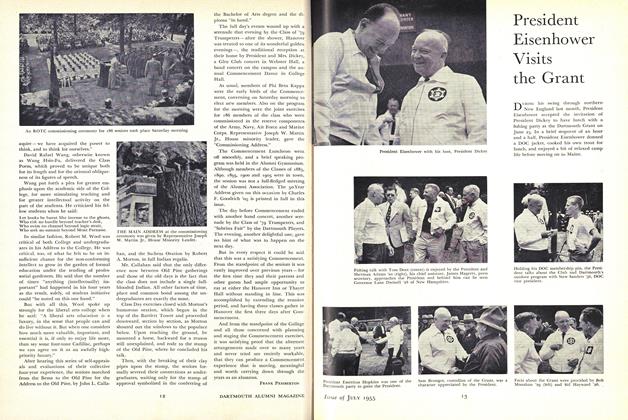

FeaturePresident Eisenhower Visits the Grant

July 1955 -

Feature

FeatureTHE COLLEGE TEACHER: 1959

APRIL 1959 -

Feature

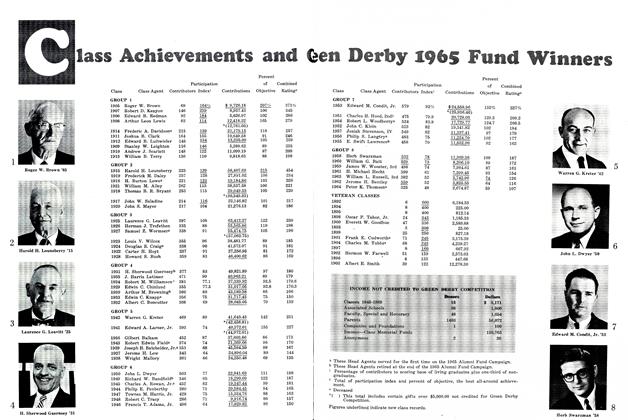

FeatureClass Achievements and Green Derby 1965 Fund Winners

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Feature

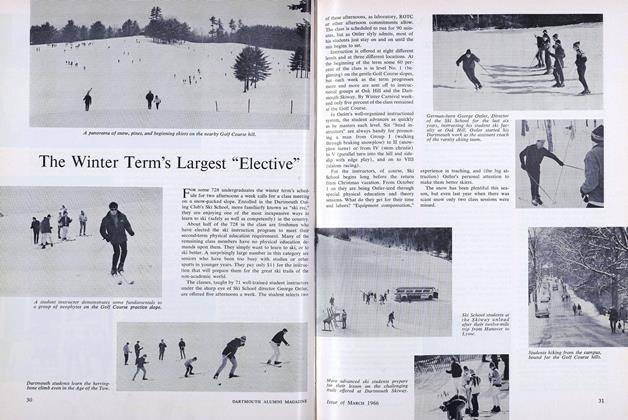

FeatureThe Winter Term's Largest "Elective"

MARCH 1966 -

FEATURE

FEATUREFly Boy

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By BROUGHTON COBURN -

Feature

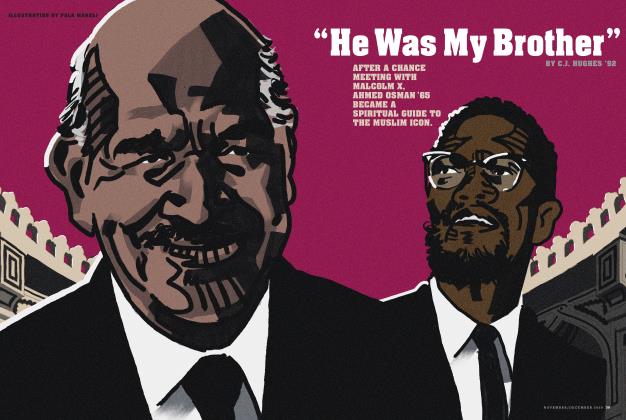

Feature“He Was My Brother”

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By C.J. Hughes ’92