HONOR: The Vanishing Principle

What is honour? a word. What is in that word honour; what is that honour? air. A trim reckoning! Who hath it? he that died o'Wednesday.

February 1975 JAMES A.W.HEFFERNANWhat is honour? a word. What is in that word honour; what is that honour? air. A trim reckoning! Who hath it? he that died o'Wednesday.

February 1975 JAMES A.W.HEFFERNANThe concept of honor seems to have become the property of

the archeologist. Looking back on the liquid sewage of

governmental corruption that has flowed out of Watergate, we

may well wonder whether it is possible to recover or reconstruct a

civilization in which honor actually existed. In what lost paradise

of unimpeachable integrity, in what Houynhym-land of inflexible

truth and faithfully kept promises, did it ever in fact prevail? The

question is not easily answered.

Periods of innocence have a way of receding into the infinite past — or disintegrating even as we try to touch them. Like the Golden Age of Greco-Roman mythology, the pre-lapsarian state of man remains an alluring but historically unsubstantiated myth. Plato's republic of perfect justice is a philosopher's ideal. The Pentelic marble of the Parthenon is real enough, but if it summons up the glory that was Greece and the exemplary statesmanship of Pericles, we should understand that Pericles plundered the treasury of the Aegean naval league in order to get it built. If we go to the English Middle Ages to find a specimen of probity in Chaucer's "verray, parfit, gentil knyght," we are dealing with a literary creation, and also with a vanishing breed: the lusty young son of this grand old crusader is clearly more bent on seducing "his lady" than on emulating his father. On our own ground, in America's age of innocence, George Washington is supposed to have told the truth about a cherry tree. But historical evidence for that story is not very substantial either, and recent events tend only to confirm the view of human nature enunciated by Robert Penn Warren's Willie Stark — the supremely unscrupulous governor in All the King's Men. Told about a man who cannot be bought or blackmailed because he has never done anything wrong, Willie declares: "Man is conceived in sin and born in corruption. He proceeds from the stink of the dy-dee to the stench of the shroud. There is always something."

And indeed there is. For Kennedy it was Chappaquidick; for McGovern it was Eagleton; for Humphrey it was (and is) illegal campaign contributions, and the men of that particular kind have lately been falling like so much presidential timber. Our new President seems the very embodiment of forthright candor, but he has not yet altogether buried the lingering suspicion that we have replaced a knave with a fool. Men of Dartmouth, of course, may give a rouse at the thought that the new Vice President is neither, and is one of our own besides; but even Rockefeller has prompted some uneasiness about the propriety of his campaign tactics and the size of his munificent gifts. Quite aside from his exceptional qualifications for the job, one is led to wonder whether he was finally confirmed because Congress at last concluded that it would never find a man who was precisely rich enough to spurn bribes but not quite rich enough to offer them.

Making the principle of honor a continuing reality at Dartmouth is scarcely less difficult than finding a politician with an unblemished record. In the fall of 1972, ten years after the honor principle replaced the proctor system, Dartmouth decided to see just how well the principle was working. The Executive Committee of the Faculty therefore established an ad hoc committee of students and faculty members (of which I was chairman), and in January 1973, we in turn sent questionnaires to all members of the faculty and to a 25 per cent random sample of students in all classes. The questionnaires were anonymously returned, and the results were not very pleasant. Of the 429 students who returned the questionnaire (out of the 798 who received it), 63 per cent admitted that they had violated the honor principle at least once. Some of them had simply taken library books without signing them out, but even if we discount those, 55 per cent admitted to clear-cut acts of cheating: breaking the rules of an examination, submitting work which was not their own, or helping others to do so. Further, nearly 42 per cent admitted to violating the honor principle more than once.

The celebrated cover-up of White House involvement in the Watergate break-in was hardly more extensive than the continuing process of cover-up which surrounds these violations. They multiply in an atmosphere of acquiescence. According to the honor principle, "a man who submits work which is not his own ... forfeits his right to continue at Dartmouth," and any student who discovers a violation is "bound by honor to take some action." Yet while 263 of our respondents said thay had known of one or more violations, 69 per cent of them took no action of any kind against the offender; the rest either remonstrated with the offender himself or reported that there had been cheating in a particular course, but with a single exception, no undergraduate has ever reported the name of an offender to the dean.

Even among faculty members, reporting is spotty. Of the 207 who answered our questionnaire, 102 told us that they had found one or more probable violations of the honor principle among their students, but 49 of these had never reported a violation to the Dean. To be sure, some departments have internal reporting procedures, and among faculty membetrs who both knew about such procedures and had detected violations, 78 per cent had reported one or more violations to their departments. But 41 per cent of our faculty respondents said that they did not know whether their departments had internal reporting procedures. What this figure probably means is that none of them had ever discussed the problem of academic honor with their departmental colleagues, and certainly not with their chairmen.

The failure of faculty members to report probable violations to the Dean helps to widen, of course, the gap between the number of violations committed and the number of cases presented to the College Committee on Standing and Conduct (CCSC). Made up of four elected students and four faculty members, and chaired by the Dean of Freshmen, this committee adjudicates every case involving the honor principle, but of course it can adjudicate only the cases brought to its attention. During a period of three and a half years, our 429 student respondents violated the honor principle well over 500 times, so it would be safe to say that the total number of violations committed by all students in this period must be well over 1,000. But during approximately the same period, from February 1968 to October 1972, only 34 cases involving the honor principle ever reached the CCSC.

To the great majority of students and faculty alike, the CCSC is an unknown quantity, for only a small number of our respondents in either category knew enough to say whether it was fair nor not. Among those who did know enough to say, most of the faculty thought the CCSC too lenient, while most of the students thought it fair. These, of course, are relative terms, and therefore not very informative. What the actual record of the CCSC shows is that this committee has been extremely flexible. The honor principle stipulates that a student who submits work which is not his own "forfeits his right to continue at Dartmouth." Strictly interpreted, this could mean that a student found guilty of cheating must be separated from the College; in practice, it has meant any number of things. Of the 34 students charged with violation of the honor principle from February 1968 to October 1972, 26 were found guilty. Of these 26, only one was separated from the College. Five were suspended indefinitely, which means that they may apply for readmission after two years; five were suspended for just one year; one was suspended for two terms; six were suspended for one term; one was suspended for a summer; one was suspended for less than one term; and six were allowed to remain at Dartmouth on probation or under College Discipline. (Suspension becomes part of a student's permanent record, whether or not he or she returns and graduates; the record of probation and College Discipline lasts only so long as the student remains at Dartmouth.

"... any kind of system run more efficiently would have to be based on implicit mistrust."

For the striking disparity in these penalties there is no simple explanation. Virtually all of the students penalized had been found guilty of either plagiarism or cheating on an examination. Nearly half of them were freshmen, and in some of these cases the CCSC seems to have made some allowances for their relative unfamiliarity with the honor principle. But two of the six guilty students who were not suspended were upperclassmen. On the whole, therefore, the record of the CCSC shows what happens when a judicial committee operates without strict "guidelines. Instead of establishing fixed penalties for specified violations, the committee has considered every case on its individual merits, and, in assigning penalties, it takes particular pains to recognize mitigating circumstances. Those who serve on the CCSC do develop a sense of precedents, and new cases are often considered in the light of old ones. But there is now no stated formula for the determination of penalties.

In any case, whatever may be said about its actual behavior, the CCSC is not generally reputed for harshness. Of the students who expressed an opinion on the committee, only 23 per cent thought it too harsh; of the faculty, only four per cent. The supposed harshness of the CCSC, then, cannot explain why so many faculty members do not report suspected violators of the honor principle to the Dean, and we must look for reasons elsewhere.

There appear to be three. The first is that teachers hesitate to take a step which might handicap a student's prospects for life. Regardless of how lenient the CCSC may be - and most faculty members have no idea how lenient it may be - a professor tends to feel that when he reports a student to the Dean, he is sending him to a kind of executioner, and that for one small offense, the student's whole future will be cut off. Few faculty members would go so far as the student who said that it was more dishonorable to report a student than to violate the honor code, but many would say that reporting a student to the Dean is not much kinder than reporting him to the police.

Secondly, a professor who reports a student to the Dean knows that he may have to be a witness against his student. Together with his evidence against the student, he must submit his testimony in writing to the Dean, and he may be called before the CCSC to testify against the student in person. Aside from the amount of time and work involved in presenting such testimony and evidence, it is at best unpleasant for the professor involved, and if the student is well known to him, it can be painful. In the face of the work, time, and unpleasantness involved, the temptation not to report a suspected violation is almost irresistible.

"... a game in which the faculty has the honor and the students have the system."

The third reason is a little ironic, since it almost contradicts the first and second. While some fear that a reported student will be treated too harshly, others believe that he will be treated too lightly, and they therefore conclude that reporting is not worth the time and trouble it takes. Both attitudes in fact may coexist in one teacher, for the whole process of reporting tends to breed ambivalence in those who put themselves through it. On the one hand, a teacher may be reluctant to harm a student whom he knows personally. On the other hand, if the same professor has taken the time and trouble to prepare a case against the student, he has a personal stake in seeing that the student is officially found guilty and sufficiently punished. But the professor may well find himself frustrated. Given the record of the CCSC, whose penalties for honor violations range all the way from separation to one term of College Discipline, he has no way of knowing what the results of his time and trouble will be. Further, the interpretation of evidence in honor cases can sometimes be highly complicated. Recently a professor charged that one student had copied from another on an examination, and to prove the charge, he presented to the CCSC evidence that seemed to him incontrovertible. The similarity between one student's work and the other's, however, was of a scientific nature, and could not be readily seen by anyone unfamiliar with the subject of the examination. The CCSC therefore disagreed with the professor's interpretation of the evidence, and the student involved was found not guilty. As a result, the professor has lost all confidence in the CCSC and will report no more violations of the honor principle to the Dean.

These, then, are the unpalatable facts: in large number, Dartmouth students are both cheating and conniving at cheating by others, and for a variety of reasons, many faculty members are choosing not to tell the Dean about the probable violations they detect. To these facts there are two kinds of reaction. One is to say that Dartmouth students are really no worse than the leaders they are being trained to succeed, that in the classroom as in the Oval Office, cheating is an inescapable fact of life, and that for all its looped and windowed raggedness, the honor principle might as well be left as it is. The other reaction is to say that something must be done, that the honor principle must be redefined and reinforced. This was the line taken by the honor principle committee.

Quixotically, we made a spate of recommendations. We urged - among other things - that every member of the faculty should every term explain the honor principle to his students; that teachers should head off cheating by avoiding such things as multiple choice examinations; and that every department should have its own honor committee to receive individual reports of violations and then share the responsibility for passing them on to the Dean. In the end, none of these recommendations was adopted, and the honor principle now stands exactly where it did when we started.

Is this situation cause for rage and dismay? It could be, but I think it rather a cause for reflection. Looking back on the resistance which greeted our recommendations in the spring of 1973,I cannot now indict my colleagues for moral flaccidity. The problem of honor is not so simple. In retrospect, it seems to me now that our recommendations sought to turn the honor principle into an honor system, and an honor system is a contradiction in terms. Honor is a principle of individual, internal self- regulation; system is a means of collective, external regulation. To oil the machinery of the second is to drain the life out of the first. As a thoughtful freshman indicated on his questionnaire, the existing honor principle is based on implicit trust, while any kind of "system" run more efficiently would have to be based on implicit mistrust. Indeed, whenever system begins to take Precedence over honor, the honor system becomes a game in which the faculty has the honor and the students have the system.

If we cannot strengthen the system without weakening the principle of honor itself, how then can we strengthen the principle? There is really no way but the way of individual resolution, and this can be elicited from students only by the suasion and example of the faculty — not by any legislative decree. Dartmouth must continue to assume that most (if not all) of its students bring a fundamental sense of honor with them, but it is part of a teacher's job, I think, to deepen that sense of honor, and to instill in his students a respect for individual initiative and genuine intellectual achievement. There is a world of difference between ac- tually knowing something and (for a moment) making someone else think you know it; between formulating a synthesis of your own and replicating someone else's; between the real eye of your own perception and the glass eye of a pilfered one. So long as grades are given, some of them will be dishonestly earned, but only a fool thinks a counterfeit grade means the same as a real one, or that any grade at all can measure precisely how much he has learned in a course.

The vast majority of those who cheat will be caught, if ever, only by themselves. But I do not think that anyone at Dartmouth can honorably abdicate his responsibility to take some action against cheating when he detects it. To connive at cheating is to pretend that appearance and reality are the same, and to encourage the pretense in others. If Watergate has taught us anything, it has shown how pestilential this pretense can be: how seductive, how corruptive, how pervasive. And if we pretend to condemn the Watergate cover-up while ourselves adopting the mentality that made it possible, we are indulging in hypocrisy and self-delusion. Academic honor at Dartmouth is not the students' problem, or the faculty's problem, or the Dean's problem. It is everybody's problem. For each of us, the quest for honor must begin with a long, hard, searching look in the mirror.

"... but with a single exception, no student has ever reported the name of an offender to the dean."

An associate professor of English, James A.W. Heffernan waschairman of the committee appointed to study the honor principle. He teaches courses in English Romantic poetry.

"... but only a fool thinks a counterfeit grade means the same as a real one."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStar Birth, Star Death, and Black Holes

February 1975 By DELO E. MOOK -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Rip-off

February 1975 -

Feature

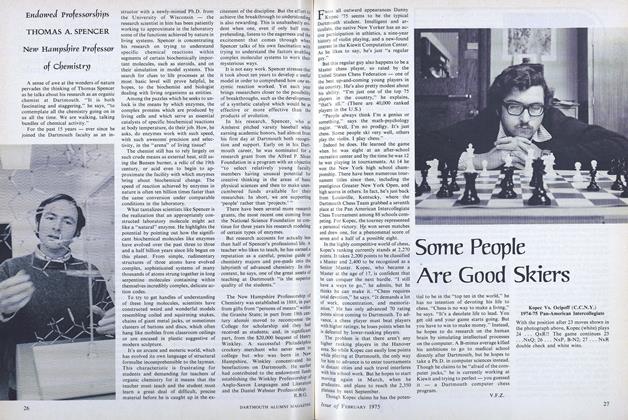

FeatureSome People Are Good Skiers

February 1975 By V.F.Z. -

Article

ArticleThe Gospel According to Marcus

February 1975 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

February 1975 By J.H. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

February 1975 By PAUL WOODBERRY, CHARLES S. KILNER

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Backward Glance at the Humanities

November 1954 -

Feature

FeatureWhere will your children go to college?

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureDinner for the Colonel

March 1977 By BRAVIG IMBS -

Feature

FeatureEducation for Management

June 1962 By CARLA A. SYKES -

FEATURE

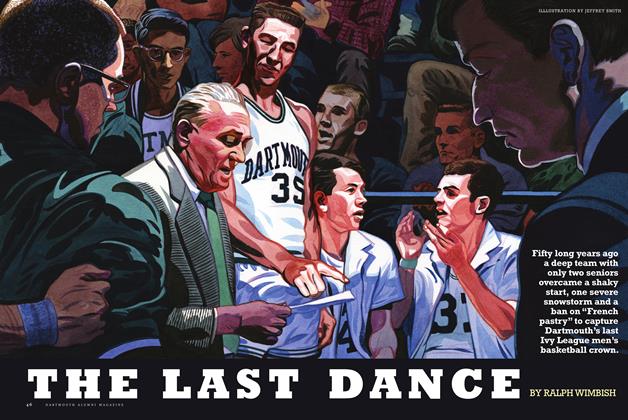

FEATUREThe Last Dance

Mar/Apr 2009 By RALPH WIMBISH -

Feature

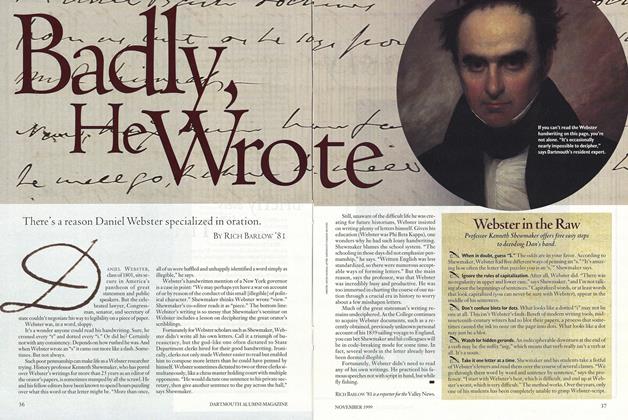

FeatureBadly, He Wrote

NOVEMBER 1999 By Rich Barlow ’81