With the assistance of a dictionary and some hazy recollections from Art II at Dartmouth, I was happily reintroduced to the work of Henri Matisse (1869-1954) by the new addition to the Abrams Library of Great Painters by John Jacobus. Professor Jacobus is a literate and perceptive writer, at times presuming upon the advanced knowledge of his readers, yet stimulating enough to send his novice audience scurrying off on indicated tangents in order not to miss his implications.

Henri Matisse working in the first half of this century created a very personal alternative to cubism and developed a unique iconography which he used to probe space and color, form and visual interaction. His avatar was the human figure, presented at rest and in motion, literally and abstractly, sympathetically and mysteriously. It is difficult indeed to summarize the career of Matisse, and Jacobus' book is most beneficial for the neophyte, the dilettante, and the well-versed alike because of its careful and methodical outline of Matisse's development. This is not to imply that the text is prosaic or even straightforward, for the evolution of Matisse as artist was a complex and many-faceted progression. But Jacobus manages admirably in keeping the reader's focus on the artist's major concerns, goals, and experiments.

Matisse began his artistic education in 1891 when he was 22 years old. He worked under academic artists in Paris and diligently copied the old masters in the Louvre. But beginning around 1908 he became increasingly involved with painting nude figures in a landscape and placing them sometimes in classical and sometimes in innovative groupings. He directed a large part of his efforts towards "a chromatic two-dimensional reduction of visual phenomena," and the figure became the favored tool with which he experimented. Professor Jacobus explores the entire range of Matisse's art, but he emphasizes the human figure as essential, especially in large-scale works.

Matisse has been called by some critics a "genius of omission," in much the same manner as Ernest Hemingway. Both artists fashioned their work so that everything that could possibly be left out was left out, or was stated by implication only, without sacrificing the completeness of the work. But the phrase is deceptive, as is the characterization "leader of the Fauves," the label which assures Matisse's historical position. Any single appellation is inadequate in pointing up the individuality and health of Matisse. He worked the whole gamut of artistic media: painting, sculpture, graphics, drawing, and book illustration. He even went beyond the conventional media, as evidenced by his late papier-découpé works and the paintings which formal frames cannot contain. Ultimately it is this diversity which makes Matisse so interesting.

Not only for scholars is this book important but also for readers with limited backgrounds. With Professor Jacobus as learned commentator, the 168 illustrations - 48 in full color - prove to be informative and challenging. Matisse is the painter in whose work the transition from French art of the 19th century into that of the 20th can be most clearly seen. Actively involved in the Fauve movement he merges as an independent modern master, and his use of color, light, perspective, and form reflects every significant development from Manet onward.

MATISSE. By John Jacobus,Professor of Art. Abrams, 1974.Illustrated. 184 pp. $22.50.

A graduate of George Washington UniversityLaw School. Mr. Yadley is now an attorneywith the Securities and Exchange Commissionin Washington.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

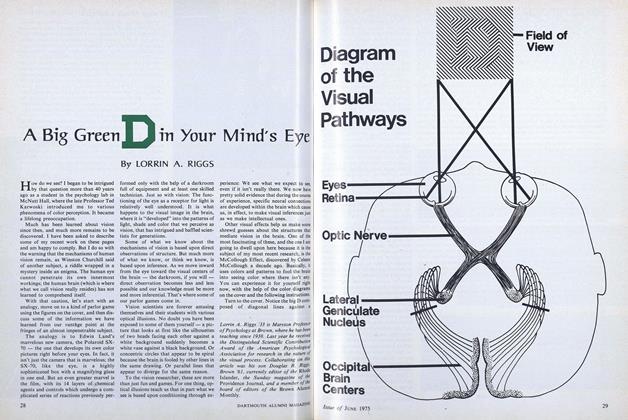

FeatureA Big Green D in Your Mind's Eye

June 1975 By LORRIN A. RIGGS -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

June 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1975

GREGORY C. YADLEY '72

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

February 1956 -

Books

BooksNORTHERN LIGHTS: WRITERS FROM THE UPPER VALLEY OF VERMONT AND NEW HAMPSHIRE.

June 1974 By CLAUDE G. LIMAN '65 -

Books

BooksON THE STAKED PLAIN

June 1940 By Mabel L. Seavey -

Books

BooksNotes on a common bond: the federal city, that summer in Philadelphia, Essex County in revolt, and disaster in Ohio

September 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksWholesome Marriage.

FEBRUARY, 1928 By Ralph P. Holben -

Books

BooksNative Wood-notes

JUNE 1983 By Wilfrid Mellers