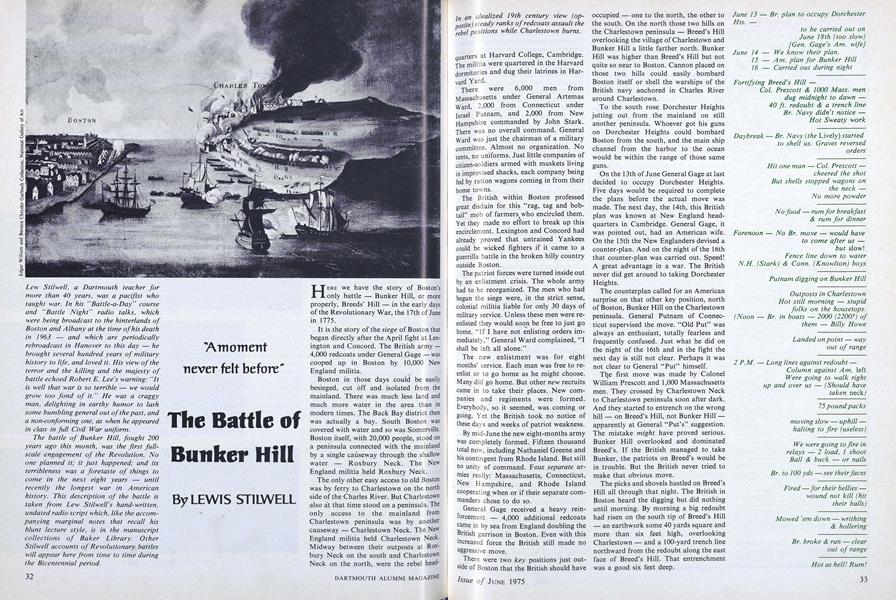

"A momentnever felt before"

Lew Stilwell, a Dartmouth teacher formore than 40 years, was a pacifist whotaught war. In his "Battle-a-Day" courseand "Battle Night" radio talks, whichwere being broadcast to the hinterlands ofBoston and Albany at the time of his deathin 1963 — and which are periodicallyrebroadcast in Hanover to this day - hebrought several hundred years of militaryhistory to life, and loved it. His view of theterror and the killing and the majesty ofbattle echoed Robert E. Lee's warning: "Itis well that war is so terrible - we wouldgrow too fond of it." He was a craggyman, delighting in earthy humor to lashsome bumbling general out of the past, anda non-conforming one, as when he appearedin class in full Civil War uniform.

The battle of Bunker Hill, fought 200years ago this month, was the first fullscale engagement of the Revolution. Noone planned it; it just happened; and itsterribleness was a foretaste of things tocome in the next eight years - untilrecently the longest war in Americanhistory. This description of the battle istaken from Lew Stilwell's hand-written,undated radio script which, like the accompanying marginal notes that recall hisblunt lecture style, is in the manuscriptcollections of Baker Library. OtherStilwell accounts of Revolutionary battleswill appear here from time to time duringthe Bicentennial period.

HERE we have the story of Boston's only battle - Bunker Hill, or more properly, Breeds' Hill - in the early days of the Revolutionary War, the 17th of June in 1775.

It is the story of the siege of Boston that began directly after the April fight at Lexington and Concord. The British army - 4,000 redcoats under General Gage - was cooped up in Boston by 10,000 New England militia.

Boston in those days could be easily besieged, cut off and isolated from the mainland. There was much less land and much more water in the area than in modern times. The Back Bay district then was actually a bay. South Boston was covered with water and so was Somerville. Boston itself, with 20,000 people, stood on a peninsula connected with the mainland by a single causeway through the shallow water - Roxbury Neck. The New England militia held Roxbury Neck.

The only other easy access to old Boston was by ferry to Charlestown on the north side of the Charles River. But Charlestown also at that time stood on a peninsula. The only access to the mainland from Charlestown peninsula was by another causeway - Charlestown Neck. The New England militia held Charlestown Neck. Midway between their outposts at Roxbury Neck on the south and Charlestown Neck on the north, were the rebel headquarters at Harvard College, Cambridge. The militia were quartered in the Harvard dormitories and dug their latrines in Harvard Yard.

There were 6,000 men from Massachusetts under General Artemas Ward, 2,000 from Connecticut under Israel Putnam, and 2,000 from New Hampshire commanded by John Stark. There was no overall command. General Ward was just the chairman of a military committee. Almost no organization. No tents, no uniforms. Just little companies of citizen-soldiers armed with muskets living in improvised shacks, each company being fed by ration wagons coming in from their home towns.

The British within Boston professed great disdain for this "rag, tag and bobtail" mob of farmers who encircled them. Yet they made no effort to break up this encirclement. Lexington and Concord had already proved that untrained Yankees could be wicked fighters if it came to a guerrilla battle in the broken hilly country outside Boston.

The patriot forces were turned inside out by an enlistment crisis. The whole army had to be reorganized. The men who had begun the siege were, in the strict sense, colonial militia liable for only 30 days of military service. Unless these men were re-enlisted they would soon be free to just go home. "If I have not enlisting orders immediately," General Ward complained, "I shall be left all alone."

The new enlistment was for eight months' service. Each man was free to re-enlist or to go home as he might choose. Many did go home. But other new recruits came in to take their places. New companies and regiments were formed. Everybody, so it seemed, was coming or going. Yet the British took no notice of these days and weeks of patriot weakness.

By mid-June the new eight-months army was completely formed. Fifteen thousand total now, including Nathaniel Greene and his contingent from Rhode Island. But still no unity of command. Four separate armies really: Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island cooperating when or if their separate commanders chose to do so.

General Gage received a heavy reinforcement - 4,000 additional redcoats came in by sea from England doubling the British garrison in Boston. Even with this increased force the British still made no aggressive move.

There were two key positions just outside of Boston that the British should have occupied - one to the north, the other to the south. On the north those two hills on the Charlestown peninsula - Breed's Hill overlooking the village of Charlestown and Bunker Hill a little farther north. Bunker Hill was higher than Breed's Hill but not quite so near to Boston. Cannon placed on those two hills could easily bombard Boston itself or shell the warships of the British navy anchored in Charles River around Charlestown.

To the south rose Dorchester Heights jutting out from the mainland on still another peninsula. Whoever got his guns on Dorchester Heights could bombard Boston from the south, and the main ship channel from the harbor to the ocean would be within the range of those same guns.

On the 13th of June General Gage at last decided to occupy Dorchester Heights. Five days would be required to complete the plans before the actual move was made. The next day, the 14th, this British plan was known at New England headquarters in Cambridge. General Gage, it was pointed out, had an American wife. On the 15th the New Englanders devised a counter-plan. And on the night of the 16th that counter-plan was carried out. Speed! A great advantage in a war. The British never did get around to taking Dorchester Heights.

The counterplan called for an American surprise on that other key position, north of Boston, Bunker Hill on the Charlestown peninsula. General Putnam of Connecticut supervised the move. "Old Put" was always an enthusiast, totally fearless and frequently confused. Just what he did on the night of the 16th and in the fight the next day is still not clear. Perhaps it was not clear to General "Put" himself.

The first move was made by Colonel William Prescott and 1,000 Massachusetts men. They crossed by Charlestown Neck to Charlestown peninsula soon after dark. And they started to entrench on the wrong hill - on Breed's Hill, not Bunker Hill - apparently at General "Put's" suggestion. The mistake might have proved serious. Bunker Hill overlooked and dominated Breed's. If the British managed to take Bunker, the patriots on Breed's would be in trouble. But the British never tried to make that obvious move.

The picks and shovels hustled on Breed's Hill all through that night. The British in Boston heard the digging but did nothing until morning. By morning a big redoubt had risen on the south tip of Breed's Hill - an earthwork some 40 yards square and more than six feet high, overlooking Charlestown - and a 100-yard trench line northward from the redoubt along the east face of Breed's Hill. That entrenchment was a good six feet deep.

It was just the right sort of position for the colonial type of soldiering. Fully protected by their earthworks, the boys could aim their muskets carefully and calmly at a close-packed line of redcoats puffing up the hill in front of them.

At daybreak the British naval vessels started to bombard the new redoubt. A cannon ball mangled to death one soldier in the redoubt, the only casualty that morning. Colonel Prescott walked up and down on top of the earthworks just to show the boys that British cannon balls were usually harmless.

One very special personage arrived at the redoubt that morning - Dr. Joseph Warren, head of the Massachusetts Committee of Safety, the civilian authority superior to Colonel Prescott and all the other military officers. Dr. Warren had decided that he himself must fight in a war for which he was responsible. So he took his place in the ranks and fought that day as a private in the army which he himself controlled.

The British warships also were bombarding Charlestown Neck, that causeway through the water that lay wide open to shellfire. The drivers of American supply wagons refused to risk their teams on that exposed roadway. This was serious, a breakdown in the supply line. No reserves of powder in the American earthworks. And those boys on Breed's Hill had nothing but rum for breakfast, and nothing but rum for dinner.

Another 1,000 reinforcements managed to cross the neck during the morning, all that General Ward in Cambridge felt that he could spare out of his total of 16,000. After all he did not yet know what the British were about to do. They might come out in force at Roxbury Neck; they might not attack Breed's Hill at all.

Some of those reinforcements were used by General Putnam to start earthworks on Bunker Hill according to the original plan This was a case of too little and too late Those earthworks were not finished and were never used.

Among the extra troops that morning came John Stark and 200 of his New Hampshire men. They joined with 200 from Connecticut under Colonel Knowlton to establish the fence line - the other feature of the American defense. That fence line ran at right angles to the main entrenchment along the east side of Breed's Hill, starting near the north end of Breed's Hill and extending eastward on low ground to water's edge on the far side of Charlestown peninsula. The fence itself was nothing much - a combination affair - a low stone wall with rails above the stones. The boys stuffed hay between the rails and prepared to fight behind this flimsy cover.

The fence line served as a protection for the American left flank - the north end - of the main earthworks along Breed's Hill. If the British tried some sort of end run around that flank between the hill and the waterside, they would first have to break through the fence line.

The British took care of the other American flank - the right flank toward the south where the big redoubt looked down on Charlestown village. British guns put hot shot into Charlestown village. The whole town caught fire. Two hundred blazing houses - flaming church steeples, smoke, cinders, ashes - were the backdrop of the battle when it began that afternoon.

Just about noon 2,000 British redcoats piled into small boats at Boston to row across the Charles River. They landed on the southeast tip of Charlestown peninsula - a half mile from Breed's Hill. Light artillery crossed with the infantry. But someone had blundered with the artillery ammunition. Six-pounder guns were provided with twelve-pound cannon balls.

General Sir William Howe was in direct command. A brave man - a veteran of previous furious battles - an able military leader when groused but often gloomily indifferent to what went on around him. Howe moved his troops to the attack in two divisions - one division under General Pigot to go up against the redoubt and the trench-line on Breed's Hill, the redcoats to advance in a long, double line, shoulder-to-shoulder up the hill. The other division, led by Howe himself, to move at the same time and in the same formation against the fence line held by Stark and Knowlton.

The British were all clad in full-dress uniforms and carrying full packs that weighed some 90 pounds. Howe's tactics were contemptuous. The Americans were to be treated as the armed rabble they appeared to be. The royal army was about to march right up to, through, and over the rebellious farmers and put them all to rout.

It was a gorgeous show. The house tops of Boston were crowded with spectators. In the bright June sunlight, the faultless ranks of scarlet moving through the deep green meadows. And not a single American in sight. But it was hot work for those regulars in their stiff uniforms under their heavy packs. Not a breath of air was stirring. There were fences to be climbed as they advanced.

Twice the two forces halted to fire volleys, unaimed volleys with heads held high as was the British custom. A shower of bullets hitting nothing and nobody for the Americans were all well hidden behind their earthworks on the hill and behind the hay-stuffed rails along this fence line. The Americans were waiting silent. "Don't fire till you see the whites of their eyes." They would aim their guns when that time came. And they would aim low - to wound the redcoats, make them suffer - rather than kill them.

The British double-lines - in both attacks - kept moving nearer. Any minute now they would close with the rebels and finish them with the bayonet. At about 50 yards the American fire burst. The British were mowed down in rows. The British officers were special targets. And the fire kept up. The Americans were shooting in relays, the best shots doing all the firing while the others loaded. Not a single British soldier reached the American line on either front. They fell back out of range leaving their comrades by the hundreds writhing in the grass.

This would never do. Howe ordered a second attack - full packs, close order in long lines on both fronts, exactly as before. The surviving officers rallied their men. The lines again were formed. Discipline was discipline, the redcoats were allowed to come a little nearer this time before the musket fire began - fast, precise, and deadly as before. More rows of wounded left behind by the retreating British. "Their fallen," John Stark said, "lay as thick as sheep in a fold."

General Howe was shaken. "There was a moment that I never felt before," he later wrote. Every one of the ten officers on his own staff had been shot down.

Howe woke up. This was no ordinary battle; it required thought. There would have to be a third assault, but it must be different. Those heavy packs were taken off the soldiers. The attack this time would be with bayonet only - no halting to fire useless volleys at invisible Americans. The attack was to be concentrated on the American strongpoint - the big redoubt. An assault in a long narrow column with only a few soldiers at its head exposed to rebel musket fire.

The British field guns had their proper ammunition now. They were well placed to enfilade the American breastworks. A few fresh troops had been brought in from Boston for this third attempt. That third attack went up the hill toward the redoubt - General Howe in the thick of it again.

The Americans were almost out of powder. Only enough for two shots per man, and they had no bayonets. Those two shots per man were fired. Not enough.

The redcoats came pouring over three sides of the redoubt - with their bayonets. The Americans could only use their muskets as clubs. Dr. Warren was killed in that close fight with many others. Colonel Prescott got out with his sword swinging. The redoubt was lost. So were the trench lines. The Americans retreated from Breed's Hill back toward Charlestown Neck.

It was an orderly withdrawal - the boys from the fence line bringing up the rear. By British testimony, "The retreat was no flight, was covered with bravery and even military skill." But it was a British victory.

The cost of victory had been too heavy in taking Breed's and Bunker Hills - 1,054 dead and wounded - 53 per cent of those engaged. It had been the bloodiest battle in the British army's entire history. General Howe had learned a bitter lesson. Always thereafter he avoided, if he could, direct assaults on American prepared positions.

General Gage was startled and embittered. He wrote to London: "These people ... are now spirited up by a rage and enthusiasm as great as ever people were possessed of. The loss we have sustained is greater than we can bear. I wish this cursed place was burned."

The American loss that day was heavy enough — over 400 - perhaps 25 per cent. There was deep chagrin at the defeat. Court martials were held to find out who had been responsible.

One great lesson had been learned - the need for a unified command - a single overall commander. That single commander was already on his way to Boston, chosen by the Continental Congress. A stranger - a proud aristocrat from Virginia - who regarded the informal Yankees, as he wrote, as "an exceeding dirty, nasty people."

New England would never have submitted to George Washington had it not been for the lesson learned at Bunker Hill.

In an idealized 19th century view (opposite)steady ranks of redcoats assault therebel positions while Charlestown burns.

"Old Put" of Connecticut - fearless butconfused - sketched by John Trumbull.

Scarcely three months after the battle aLondon engraver produced this plan of thefighting (top) and British-occupied Boston.

June 13 - Br. plan to occupy DorchesterHts.- to be carried out onJune 18th (too slow)[Gen. Gage's Am. wife]June 14 - We know their plan.15 - Am. plan for Bunker Hill16 - Carried out during nightFortifying Breed's Hill - Col. Prescott & 1000 Mass. mendug midnight to dawn - 40 ft. redoubt & a trench lineBr. Navy didn't notice - Hot Sweaty workDaybreak - Br. Navy (the Lively) startedto shell us. Graves reversedordersHit one man - Col. Prescott - cheered the shotBut shells stopped wagons onthe neck - No more powderNo food - rum for breakfast& rum for dinnerForenoon - No Br. move - would haveto come after us - but slow! Fence line down to waterN.H. (Stark) & Conn. (Knowlton) boysPutnam digging on Bunker HillOutposts in CharlestownHot still morning - stupidfolks on the housetops.(Noon - Br. in boats - 2000 (2200?) of them - Billy HoweLanded on point - wayout of range2 P.M. - Long lines against redoubt - Column against Am. left Were going to walk rightup and over us - (Should havetaken neck) 75 pound packsmoving slow - uphill - halting to fire (useless)We were going to fire inrelays - 2 load, I shoot Ball & buck - or nailsBr. to 100 yds - see their facesFired - for their bellies - wound not kill (hittheir balls)Mowed 'em down - writhing& holleringBr. broke & ran - clearout of rangeHot as hell! Rum!2nd A ttack - c. 2:30 - same as before - Up to 50 yds. this time.Hit their officers Billy Howe'sstaffBr. broke and ran againWe were safe - almost unhurtBurning of Charlestown - Hot shot fromBr. batteries onCopp's HillWhole town in flames - 300 houses Steeples toppling - Women & childrenHot ashes3rd A ttack - Br. fresh troops - took off packs - big column against theredoubt trenchline only!no stopping to firebayonet only - (knives)Came up faster —We waited —But only 2 rounds ofpowder left - NO CANNON Fired at 20 yds. butcouldn't stop them - Clubbed muskets - Br. coming in on 3 sides - Bayonets in bellies & backsWe got out - Fell back in sort of orderBoys from fence-linecovered our retreat (?)To Winter Hill - prepared to hold-Br. stoppedat Charlestown NeckWe Lost!But Br. 45 ofs. dead &wounded - Greatest killing inhistory.Dirty wounds in Br. hospital.Am. loss 25%Results - Am. entrenchments - WinterHillneed for unity of command (Washington)fortificationBr. loss - 45%Gage ready to give up - Plans to withdraw - lack ofships"The loss we have sustainedis greater than we can bear - I wish this cursed placewas burned" - Gage

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

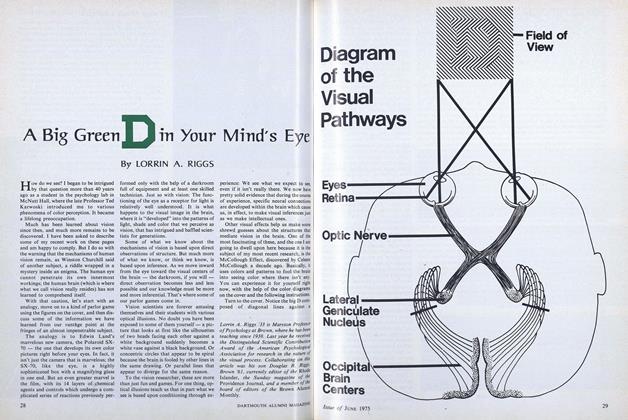

FeatureA Big Green D in Your Mind's Eye

June 1975 By LORRIN A. RIGGS -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

June 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1975 -

Article

ArticleRetiring Professors

June 1975

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTIME OUT ... REUNION

JUNE 1963 By Abnez Dean -

Feature

FeatureWhat Will Bring Me Back

MARCH 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92, Richard Hovey -

FEATURE

FEATUREMeanwhile, In Illinois

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryListening for the Silences

APRIL • 1985 By Laurence Davies -

Feature

FeatureIn Too Deep

July/Aug 2009 By PETER HELLER ’82 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Makes Nice People Nice?

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By TERESA WILTZ ’83