IN the early months of 1775 Bunker Hill was very remote from Hanover. The town had been settled for ten years but the inhabitants were few in number and those living at Dartmouth, opened five years before, were equally few. They must all have been more concerned with struggles for survival and growth than with the clashes increasingly taking place between the colonists and the British far to the south. Yet the battle of Bunker Hill came home to them in a most unexpected way.

In 1767 Timothy Smith, with a large family, had come up the river from Connecticut to settle on a large tract of the primeval wilderness stretching back from the banks of the river about three miles north of the present town of Hanover. He and his sons and sons-in-law set to work to cut down the giant pine trees and clear the land for their farms and homes. It has been my good fortune to read some of the accounts of those times written by the Smiths and their descendants. Among their papers is a letter, written about a century later, by a great grandson of Timothy relating what he heard from his ancestors about their life. In it I read the following paragraph:

When the battle of Bunker Hill commenced my grandfather was plowing on his little farm in Hanover. The cannonading, he said, he heard very distinctly and the ground was jarred very perceptibly. The old veteran unyoked his oxen, left his plow and started for Boston.

It seemed an incredible story that these sounds could be heard from 140 miles away, and I wondered if there might be any verification of the report. I wrote to Kenneth Cramer, Archivist of Baker Library, to ask if there were other references to the phenomenon. He has told me of two other reports. In Chase's History of Dartmouth College andHanover, N. H. there is this footnote:

Wheelock records in his Diary as follows: "June 16 [Saturday] - The noise of cannon, supposed to be at Boston, was heard all day! 17th, - The same reports of cannon. We wait with impatience to hear the occasion and event." These sounds of cannon were heard that day in other towns, - in Hartford [Vermont] and Lebanon, and also in Plymouth. They were noticed first in Hanover by one of the Indians, Daniel Simons, a Narragansett, of the class of 1777, who chanced to be lying with his ear to the ground, and afterwards by others, whose attention he called to them. They were universally attributed to the battle of Bunker Hill, and were certainly contemporaneous with it, - they could, indeed, have come from no other source. Strange as the facts may appear, they are too well authenticated to be doubted."

The other reference is found in a book published in Concord, New Hampshire, in 1824, Collections, Historical andMiscellaneous," Vol. III, edited by J. Farmer and J. B. Moore: "June 17, 1775, the sound of the battle at Breed's Hill was distinctly heard at Plymouth by lying the ear to the ground. Col. Webster ordered the long roll to be beaten, collected the hardy emigrants, and held a council."

The statement by President Wheelock is inexplicable. The word "Saturday" was inserted by Mr. Chase, and it is possible that Wheelock may have been confused about his calendar, nor was there any fighting on two days, only on the 17th. I have tried to get from geologists some comment about the transmission of sound as reported by the Indian but have received none yet. Seismic devices today record earthquakes at great distance, so the report he gave" seems quite possible. Though these accounts are in part at second hand, they come from diverse and reliable sources and I think that we cannot disregard them but must recognize that something unusual happened.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

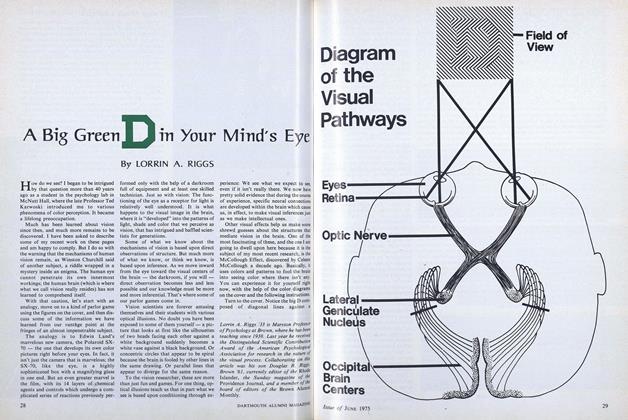

FeatureA Big Green D in Your Mind's Eye

June 1975 By LORRIN A. RIGGS -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

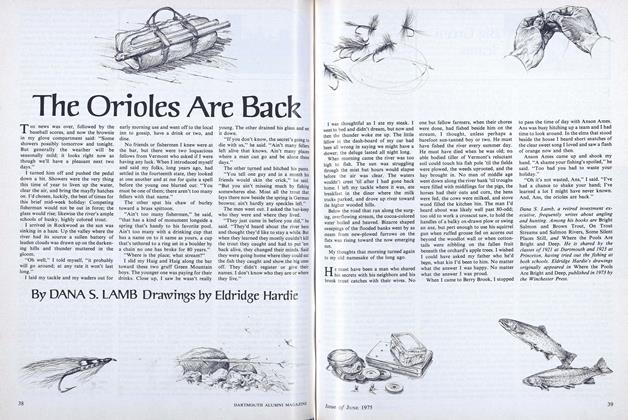

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Article

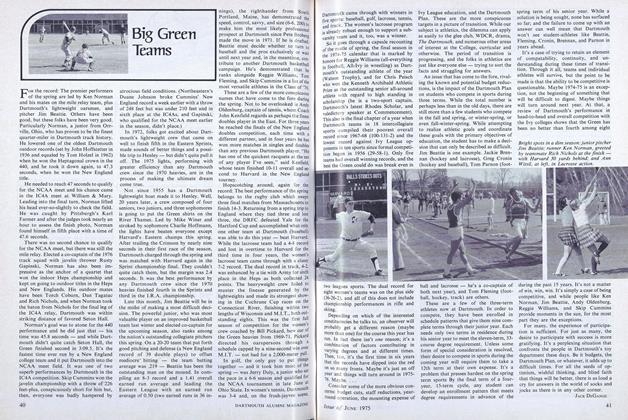

ArticleBig Green Teams

June 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1975

ARTHUR H. LORD '10

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

March 1960 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDIOR

JUNE 1964 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

SEPT. 1977 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

May 1981 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

NOVEMBER 1984 -

Feature

FeatureEVEN DISAGREEING WITH HIM WAS PLEASANT

May 1955 By ARTHUR H. LORD '10