James Thurber, with Harold Ross and E. B. White, set the tone of The New Yorker, a "humorous" magazine whose reputation is matched only by Punch, if by that. He himself caused more hilarity in the Republic, if not in the Western World, than anyone since Mark Twain. Yet this biography is a sad one, raising such questions as: what is the thin line between genius and insanity and who of us is normal?

He came from a family of eccentrics: his mother was one and another female relative really did believe the electricity was leaking all over the house; they suffered from "nerves"; his father was lovable but fearless. His younger brother shot out James's left eye with a bow and arrow when he was seven; the other eye gradually became affected so that eventually, after five operations, he became blind. He drank too enthusiastically; in his last years he was practically paranoid if not manic-depressive. In his cups he insulted people, was often violent. To cap it all, he suffered acutely from logorrhea and logomachy, along with Shakespeare, Lewis Carroll, and James Joyce. This affliction accounted for much of his wit as his uniquely zany drawings accounted for much of his humor. And somewhere in his genes lurked the demon of a mad fantasy.

This demon inhabited in its youth a middle class, middle-western environment. At Ohio State he wrote an "epic poem" to a football hero (who later landed in a mental hospital); wrote musical shows (or the librettos for them); edited the Sundial; made Phi Kappa Psi, and at the same time developed a passion for Henry James's The Ambassadors. He had a strong Puritan streak and so was a tepid and un- satisfactory womanizer. In spite of his fear and dislike of women, they fell for him. He was married twice; his second wife - his "seeing-eye wife" - cared for him with heroic devotion in his last tempestuous years.

He disliked Freud and would baffle any Freudian: one of the virtues of this biography is that Bernstein happily refrains from any attempt at psychoanalysis. Another virtue is that by its division into three parts - Innocence, Sophistication, and Angst - and its deft and pithy comments the author epitomizes the first 75 years of this American century. A trivial example of this: at one point I said to myself, this Thurber family reminds me of the origins of our recent President; a few pages later, commenting on one of Thurber's priggish letters, the author says: "It could have been a letter written by the young Richard M. Nixon."

Bernstein closes his biography, with E. B. White's moving New Yorker obituary in which he cites as his favorite "The Last Flower," that minor American classic with a universal significance in this atomic age; and he says "he wrote the way a child skips rope, the way a mouse waltzes." This is the artist, the "quintessentially human Thurber," Bernstein captures in a biography worthy to be set beside Wallace Stegner's biography of Bernard De Voto and Lawrance Thompson's life of Robert Frost.

THURBER: A BIOGRAPHY. ByBurton Bernstein '53. Dodd, Mead,1975. 505 pp. Illustrated. $l5.

Mr. Morse is Professor of English Emeritus, Dartmouth College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

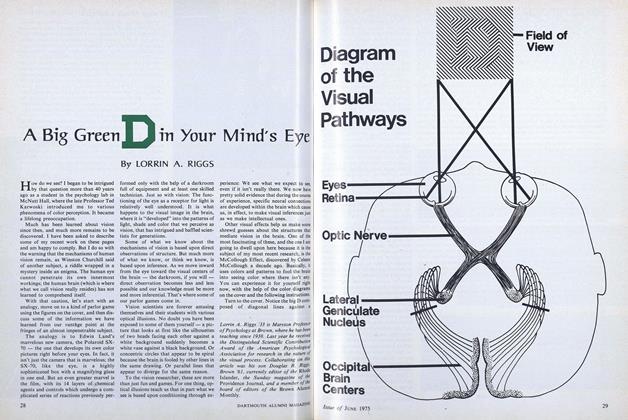

FeatureA Big Green D in Your Mind's Eye

June 1975 By LORRIN A. RIGGS -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

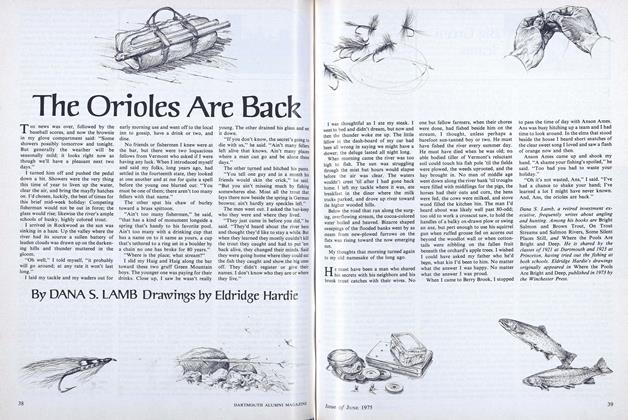

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Article

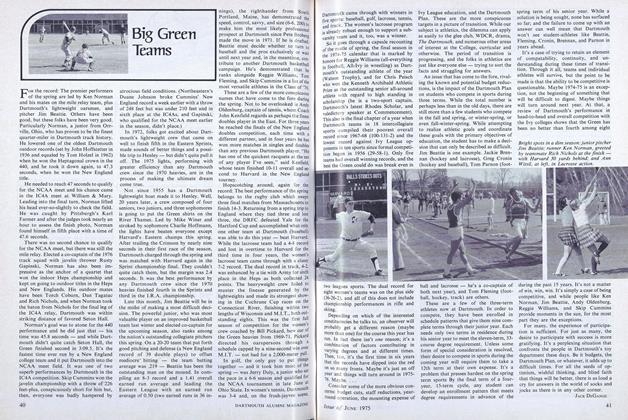

ArticleBig Green Teams

June 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1975

Books

-

Books

BooksSaints Legend

March 1917 -

Books

BooksFRONTIER OHIO

May 1936 By Allen R. Foley '20 -

Books

BooksROSANJIN: 20th CENTURY MASTER POTTER OF JAPAN.

JUNE 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksPHYSICAL CHEMISTRY FOR STUDENTS OF BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE

June 1933 By John P. Amsden -

Books

BooksStories With Purpose

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2020 By JOSEPH BABCOCK '08 -

Books

BooksON THE TEACHING OF LAW IN THE LIBERAL ARTS CURRICULUM.

June 1957 By ROBERT K. CARR '29