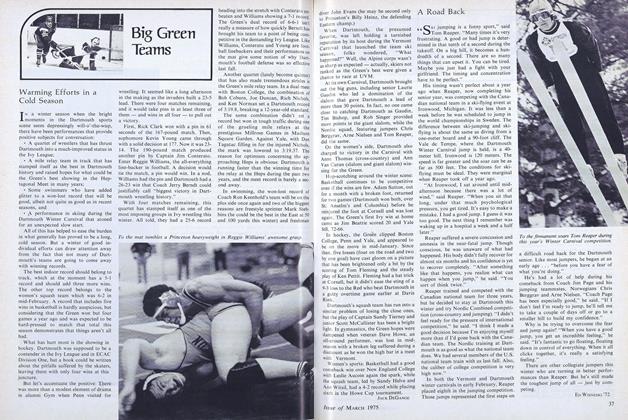

WHEN Bill Pickard spots a tall, well-built coed on the Dartmouth Green, he doesn't stare - he runs after her. Pickard is the women's crew coach, and a five-foot ten female means the same to him as a six-foot four 230-pound prospective tackle to Jake Crouthamel.

Pickard, who was co-captain on the 1971 Dartmouth heavyweight eight, is the type of guy who'd be great at a singles bar. Once he's cornered his target, he can be very persuasive: "Do you row? Why not? You could be good at it. Come to our meeting, and...."

His recruiting methods have been remarkably successful. Last fall, 200 women showed up for the first organizational meeting. Pickard lined them up by height. At one end stood Laurie Branch, 4 feet 10¼ inches, an 88pound freshman from Olean, New York, who had neither seen nor heard the word "coxswain" until a friend wrote it on a piece of paper and urged that she try to be one.

Near the other end of the line was Hope Stevens, who weighed 88 pounds in the second grade. Stevens, a six-foot, 170-pound senior from Concord, Massachusetts, had rowed at .Dartmouth for two years after transferring from Vassar as a sophomore. "When I saw Laurie, I thought she was somebody's little sister," Stevens recalls. Branch just gazed up in awe at the assemblage.

Stevens, Branch, and senior Martha Johnson from Manlius, New York, were all invited to the national camp in Boston at which Harvard coach Harry Parker will select a women's eight and four-with-coxswain to compete in the Olympics at Montreal in July. Stevens and Johnson row in the No. 5 and 6 seats respectively on the varsity eight. Branch, who has come to be known as "Twiglet," is cox of the novice shell that won the New England Open Regatta against six varsity crews and finished second in its class at the Eastern Sprints.

'Laurie Branch has been responsible for a great deal of our success," says Mike Winer, coach of the novice crew and captain of the Dartmouth lightweight eight last year. "She's picked it up amazingly fast and is extremely perceptive and creative. When she senses something wrong during a race, she has the knack of saying the right words to bring eight individuals in pain together as a team."

Stevens was overweight and out of shape before she turned to rowing. "I had no idea of the training involved when I began," she admits. "I'd never run a mile before in my life. I competed in high school, but you didn't have to be in great shape."

In the winter, all of Dartmouth's crews go through rigorous workouts involving running, cross-country skiing, weightlifting, and training on the ergometer, a torturous device that measures the strength and stamina of the "victim" pulling a simulated oar. Many women quit the winter training program, unwilling to work so hard for 30 or 40 minutes of racing in the spring.

"I've made some mistakes treating them like guys," Pickard admits. "The idea of training, winning and losing, putting on a uniform and performing is all new to most of the women because they don't come from an experienced athletic background. They're learning 15 years of athletics in six months.

Stevens often considered quitting when she started. "When I began," she says, "I used to say, 'I hate this, it hurts. What am I doing this for?' Rowing is a brutal sport. You have to push yourself past what you think you can do. There aren't many women who are used to it. You have to be tough mentally because of the way you beat your body to the point where it's almost not fun.

"But crew is fun in a different way. It's the ultimate team sport. There's a great sense of camaraderie. You row together, groan and complain together. You just can't beat that tremendous feeling of accomplishment when you're zooming across the water in harmony with eight other people who have put so much effort into it. When you row a really good race, it all seems worth it."

Laurie Branch (left) and Hope Stevens both stand tall for the Dartmouth crew.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA four-and -a-half-ounce magic totem pole

June 1976 By NORMAN MACLEAN -

Feature

FeatureTHE OLD ROMAN SPEAKS TO US STILL

June 1976 By DAVID SHRIBMAN -

Feature

Feature231 Years for Dartmouth

June 1976 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Article

ArticleCollege with an Upper-case "C"

June 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

June 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE