Summer on a farm and the livin' is easy

SILENT, the fly fell forward, sliced in half, none too neatly, by the swatter. With a jerk of the wrist, practiced by now, I scooped the remains upon the leading edge of the swatter and flung them to the floor. I resumed rocking, swatter cocked.

On the other side of the bay window, the gaggle of geese strutted by, single file, and stopped. Heads erect, they looked about, I had murderous thoughts about them, too.

My wife Martha had cut some zinnias and Queen Anne's lace and put them in a pitcher. As she set it at the center of the table where I rocked, she said, "It gets me, how everything is free in the country." I slapped my thighs.

Last spring, when I was safely at my workaday job in the city earning days of vacation, a phone call came from friends, Steve and Pam, two farmers in upstate New York. Would my family like to care for the farm while they went camping in the Adirondacks? We could raid the garden daily and tend to the animals. There would be goats to milk, eggs to gather. The kids — my human ones, Kate and Gabriel — could sleep outside in the tent by the pond. They could climb the hill and look for miles. We should bring a fishing rod.

I had always had reverence for farmers. Obsequiously, I accepted my dependence on them. I sympathized with them in their endless battles with everything from weather to the government. I bought into their own myths of satisfaction in an honest day's work close to nature, of agricultural abundance that permitted abundance elsewhere in American life, of their self-reliance and independence. I did not care how maudlin my sentiments were until the phone call came, inviting me to ground them in real soil.

As farms go, Steve and Pam's is small potatoes. It is not their bread and butter. Even with the goats, it is not their butter. It comprises three acres. The garden occupies only a fraction of that, and it contains, among other things, corn, zucchini, strawberries, and a variety of green bean which Pam says grew once in her grandfather's garden and can be found nowhere else in this region.

What makes it a farm, despite its size, is the animals. I learned this from a book. In First Person Rural, Noel Perrin, the Dartmouth professor of English who styles himself a "sometime farmer," says, "The difference between 'a place in the country' and a farm is chiefly a matter of livestock." Even 200 acres is only a place, he points out, until you put a cow in the pasture. I figured goats would serve as well.

What makes it even more a farm, I have since concluded, is the attitude of those who work it. Inactive areas of Perrin's 100 acres rise to the peasant dignity of a farm on the strength of the grit Perrin expends on the active areas. He does not say so. It is implied in the zeal with which he taps for maple sugar or builds a fence.

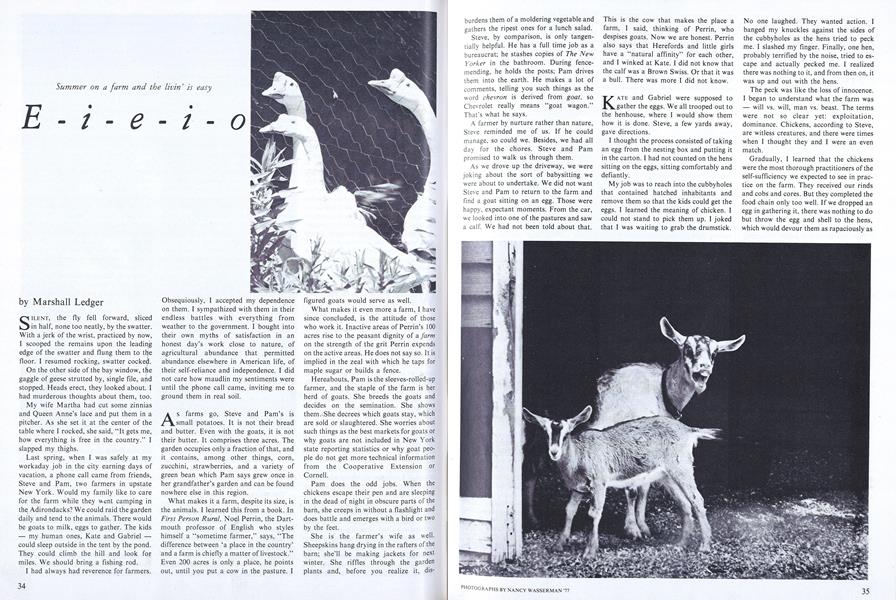

Hereabouts, Pam is the sleeves-rolled-up farmer, and the staple of the farm is her herd of goats. She breeds the goats and decides on the semination. She shows them.'She decrees which goats stay, which are sold or slaughtered. She worries about such things as the best markets for goats or why goats are not included in New York state reporting statistics or why goat people do not get more technical information from the Cooperative Extension or Cornell.

Pam does the odd jobs. When the chickens escape their pen and are sleeping in the dead of night in obscure parts of the barn, she creeps in without a flashlight and does battle and emerges with a bird or two by the feet.

She is the farmer's wife as well. Sheepskins hang drying in the rafters of the barn; she'll be making jackets for next winter. She riffles through the garden plants and, before you realize it, disburdens them of a moldering vegetable and gathers the ripest ones for a lunch salad.

Steve, by comparison, is only tangentially helpful. He has a full time job as a bureaucrat; he stashes copies of The NewYorker in the bathroom. During fencemending, he holds the posts; Pam drives them into the earth. He makes a lot of comments, telling you such things as the word chevron is derived from goat, so Chevrolet really means "goat wagon." That's what he says.

A farmer by nurture rather than nature, Steve reminded me of us. If he could manage, so could we. Besides, we had all day for the chores. Steve and Pam promised to walk us through them.

As we drove up the driveway, we were joking about the sort of babysitting we were about to undertake. We did not want Steve and Pam to return to the farm and find a goat sitting on an egg. Those were happy, expectant moments. From the car, we looked into one of the pastures and saw a calf. We had not been told about that. This is the cow that makes the place a farm, I said, thinking of Perrin, who despises goats. Now we are honest. Perrin also says that Herefords and little girls have a "natural affinity" for each other, and 1 winked at Kate. I did not know that the calf was a Brown Swiss. Or that it was a bull. There was more I did not know.

KATE and Gabriel were supposed to gather the eggs. We all trooped out to the henhouse, where I would show them how it is done. Steve, a few yards away, gave directions.

I thought the process consisted of taking an egg from the nesting box and putting it in the carton. I had not counted on the hens sitting on the eggs, sitting comfortably and defiantly.

My job was to reach into the cubbyholes that contained hatched inhabitants and remove them so that the kids could get the eggs. I learned the meaning of chicken. I could not stand to pick them up. I joked that I was waiting to grab the drumstick. No one laughed. They wanted action. I banged my knuckles against the sides of the cubbyholes as the hens tried to peck me. I slashed my finger. Finally, one hen, probably terrified by the noise, tried to escape and actually pecked me. I realized there was nothing to it, and from then on, it was up and out with the hens.

The peck was like the loss of innocence. I began to understand what the farm was - will vs. will, man vs. beast. The terms were not so clear yet: exploitation, dominance. Chickens, according to Steve, are witless creatures, and there were times when I thought they and I were an even match.

Gradually, I learned that the chickens were the most thorough practitioners of the self-sufficiency we expected to see in practice on the farm. They received our rinds and cobs and cores. But they completed the food chain only too well. If we dropped an egg in gathering it, there was nothing to do but throw the egg and shell to the hens, which would devour them as rapaciously as anything from our table. If this happened often, we were warned, they would develop a taste for their own creations and cannibalize the whole eggs before we came along with our cartons.

" Are you sure you don't want to back out?" yelled Steve as he backed their car down the driveway. They actually left the farm to us. We went exploring.

The farm had a pasture in front of the barn for the calf, named Marty, destined to be veal cutlets, and two sheep, one which was suspected to be pregnant. Martha and I watched almost hourly for a lamb, but none was forthcoming. The pregnancy turned out to be false, we learned later, and the ewe died. There were two other pastures, one in back of the barn for the goats and one beyond the goats' fence. Each area was defined by a welded wire fence, four feet high, topped by a hot wire. This apparatus did a good job of keeping predators - dogs mostly - out.

Pam told us what to expect to happen, sooner or later, on the wire. Even she had stumbled once and fallen against it, grounding it and sizzling her upper lip. Area teenagers like to grab it and see how long they can hold on. Kate did not find this amusing. She was the first one of us to touch it. It felt as if someone had hit her in the back, she reported. She was so surprised, she did not cry — until the second time. One of the goats had once gotten her horns caught in the fence and was shocked repeatedly, we learned. After being released, she showed the effects of it for' a few days, once tearing after a goose and killing it.

THE romance of it all was being discharged. Only the goats and the zinnias kept alive our original goal of getting to feel like "woodchuck farmers" — the interloper's name for the indigenous and real hill folk. The goats were especially helpful. We got close to them. To milk them, we had to lean in against them, persuade them cannily to cooperate, and have our arms just right so their hind legs would not step into the bucket.

The goat, some say, is a poor man's cow. The goat, I learned, is much maligned. It does not eat all the tins and junk that stereotype serves it, although one did nibble for taste at the Woolrich tag on Martha's bush pants. Pam has a book that says goats are more efficient than cows for underdeveloped countries, and urban folk claim that goat milk builds up immunity to poison ivy. Goats laugh at extravagant claims on their behalf; I have heard them. Milking goats is not easy. They demand that you outwit them. Milking occurs twice a day (thus the farmer on the difference between the farm and jail: "In jail, I don't have to milk every 12 hours"). The goats gathered outside the barn and watched. Inside, there are stanchions, keyhole-shaped cutouts in a solid-board fence with a feeding tray on the other side. We put an appetizer on the tray. If a goat had a mind to, she ran over, stuck her head through the larger part of the opening, and began to eat. We hooked her in place by a chain and snap that prevented her from lifting her head out.

When all were stationed, we led them, one at a time, to a platform and gave them their entree — the same food, but more of it. Not more than a designated amount, however, because they cannot digest it. While they ate, we milked. We encircled the top of the teat with a thumb and forefinger, squeezed, and enclosed the remainder of the teat with the other fingers.

Sometimes we were masterful - solid, audible squirts, one after another. We weighed our take before filling Marty's bottle; at three months, the calf could have drunk 20 pounds if we could have gotten it. And we took our own. Drinking the milk was sensually satisfying. It perfectly complemented the corn, which we waited to pick until the water was boiling.

When we were still milking under Steve and Pam's tutelage, Kate made a comment which briefly suggested we had done well to come out here. "I'd rather have this milk," she began.

David, who is Steve and Pam's son, said, "Is it better than cow's milk?" He, of course, did not know.

"I never had cow's milk," said Kate. "I just get regular polluted city milk."

You cannot finish milking a goat before it completes its meal unless your forearms are in shape. Ours were not, and often a goat grew impatient and kicked and tipped the bucket. We were further worried because we had been told that when the quantity decreases, you cannot work it up again until the goat gets pregnant the next spring. We saw our quantity drop off gradually. Our fingers ached. We would brush off a fly (the flypaper all around was teeming with victims), and a goat would seize the instant to kick over the bucket. Then it would gloat.

The goats gave us social and personal esteem. After cleaning the barn one morning, I went to a nearby shopping mall. Standing still at one point, I smelled goats and the barn on me and said, shucks, I'll call myself a woodchuck farmer. Martha and I confirmed our new status that evening as we undressed for bed. It was not yet 9:00 p.m., and we were tired — one mark of a farmer. And there were other marks. Martha had hay in her navel. I had dead sticky flies in my shirt.

THE nine goats and kids we tended made us feel a bit more human about the farm. The half of goat in the freezer made us feel a bit less. We never saw it, but knowing about it only enhanced the dramatic irony of everything around here chewing on something else for survival. Our throats tightened.

In an abstract way, Martha and I sometimes talk about becoming vegetarians. We talk about it neither deeply nor long — just when meat prices come to mind, or warm anecdotes about George Bernard Shaw. But the absolute slaughter on this vacation appalled us. We took a break from the wars to visit a stream just off a nearby highway. The big find was a sun-starched skin of a frog, long picked clean. We returned to our grim little island.

The more efficient the farm was, the worse it seemed. The Japanese beetle tray was a diabolical model of efficiency. It consists of a jar with a few inches of water. Instead of a lid, it supports a funnel with a cylinder containing the sexual parts of thousands of beetles. The live ones are attracted and fall through the funnel into the water, where they drown. The beetles actually do devastate plants, but their greed was exceeded by their lust, judging from the bottle. Even this, however, was exceeded by the glee of the chickens when we periodically threw them the contents of the jar.

The white-faced hornets, on the other hand, were not efficient, or did not seem so. They lived in a hive by the outdoor tent. Steve told us they eat flies. "That's why we're not too upset about them," he said. I watched them a while. They did not seem to catch any. "The flies are almost always quicker," Steve agreed. "We don't know how the hornets live. They're stupid."

But I was not seeing much virtue in being smart. Steve and Pam speak articulately and infectiously about homesteading. "More self-sufficiency, or less dependency," is the way Steve puts it, as he alludes to the breakdown of so many of our normal systems — social, economic, ecological. Steve and Pam use an electric pump for their deep well, and they have to buy grain from Agway, but they look on themselves as reasonably self-sufficient, considering their space.

And the rewards? I understood the pleasure in practical work and the concrete, problem-solving sort of creativity it demands. But my independence seemed a sham. Being conscious of the food cycle, I became more beholden to it than any other creature on the farm. My freedoms were lessened, not increased. There is no harmony with nature, if harmony implies peace. I would have cried out that nature was red in tooth and claw if I had not already pictured some woodchuck codgers slapping their thighs. In a book on homesteading, I had read that a successful homesteader either would have been or had been successful in the city. I can imagine why. To succeed anywhere, you have to be a shark.

In my despair, I picked up the fly swatter, which had "Holiday Inn" written on the handle, and wasted a few flies. Then I browsed through an evangelical homesteading magazine, in which the editor wrote of "a certain spiritual link" between himself and animals he raised and slaughtered; in an editorial elsewhere in the magazine, he criticized non-homesteaders for living out of sync with nature because they can go to a market for strawberries or lobster "whenever it pleases them."

At about this time, the geese went trooping by. Geese, I observed, have an objectionable carriage, which makes them appear misanthropic. Many people have this reaction, and long acquaintance with geese does not lessen it. Even such humanists as E. B. White and John McPhee show no prejudice so quickly as a prejudice against the way they take geese to perceive them. Sometimes on the farm, it was fun to confirm a cliche - crying over spilt milk, for instance, just after you have given the goat enough room to kick the full bucket into your lap. But it was not fun to be irrationally anti-goose. And you want to blame the geese for that.

The daily program of these geese was also repugnant. They strutted by, the same one always in the lead; his name, I think, was Boris. He stopped, and the others bumped to a halt like freight cars on the old Boston and Maine. He assessed the way. He strode out after it. The others followed. There was no independent gleam in their eyes, and harmony with nature was the last phrase you would apply to their relationships with any creature crossing their path.

I felt the geese were calling me an imposter of a homesteader and urging me to pack up and get out. They were like a parody of an animal that had detected a parody of a farmer. Their droppings were clogging our footpaths, which, Martha pointed out, had been clean when we arrived. The geese themselves, it turned out, did not belong loose. They had escaped from the upper pasture. I was convinced they were my Doppelganger and, like a man forced to foreknowledge of his own nightmare, I waited for them to turn the farm upside down.

One day, the geese were parading by the calf s pasture when the last goose somehow became separated from the others; it retreated while the others circled the top of the pasture, until they could see each other across the distance. From each side arose complaints, railings, and cries of distress that drew every cat in the county.

The isolated goose was not wise enough to take a few steps toward the barn and come across the top of the pasture to meet the others. This was a path we had seen them trace out at least 25 times daily; the least amount of intelligence would have served well. Instead, the ruckus increased. The lone goose jumped up and down, waving her wings. She scared the calf, who began a gallop across the pasture and, tucking his legs under him, cleared the fence, hot wire and all.

A dog, says an old tale, laughed at such sport. I could not. I raised my own cry. Martha appeared from the house, sized up the situation, and led Marty back to the pasture by his bottle. I began explaining the whole thing, laying proper blame on the geese, when I realized I was shouting over a din that had already subsided. The geese were gone, somehow reunited and strutting off in the distance.

Marshall Ledger previously wrote abouthis Dartmouth class (1961) and theattempt, at its 15th reunion, to cope withmid-life "passages." He is staff writer for The Pennsylvania Gazette, the alumnimagazine of the University of Pennsylvania.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature'We will all make whoopee'

June 1979 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

FeatureExit with a Flourish

June 1979 By Beverly Foster -

Feature

FeatureEncouraging growth, affirming the educational process

June 1979 By Robert Kilmarx -

Article

ArticleCommencement

June 1979 By James L. Farley -

Article

Article'Radical' with a Cause

June 1979 By Tim Taylor -

Article

ArticleThe Bottom Line

June 1979

Marshall Ledger

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

JULY 1959 -

Feature

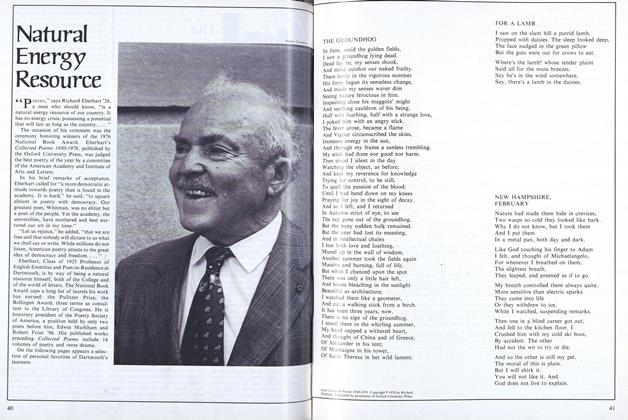

FeatureNatural Energy Resource

May 1977 -

Feature

FeaturePsychology at Dartmouth

February 1958 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Feature

FeatureLate Afternoon Thoughts On the Twentieth Century

September 1986 By LEWIS THOMAS -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO PACK LIKE A PRO

Sept/Oct 2001 By NELSON ARMSTRONG '71 -

Feature

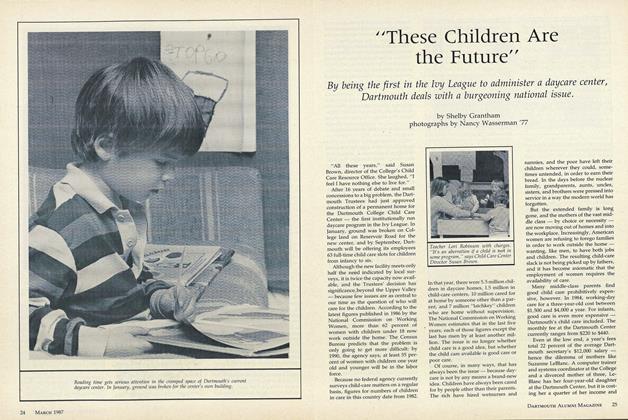

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham