The Class of '61 confronts itself—at a reunion of all places

"WHAT did our class contribute to me Dartmouth?" a classmate asks me, a puzzled look on his face. We are among hundreds having dinner at tables set up on the floor of the Thompson hockey arena. That in itself ought to puzzle us, but the ice has been removed, and this unlikely setting is surprisingly accommodating. The arena is clean and architecturally pleasing; and despite endless rows of banqueters, some warmth is emerging from this buffet.

This feeling urges him to repeat his reckless question. "Did we do anything?" He isn't referring to money. The Class of '62 has already set an Alumni Fund record for a 15th reunion class, and ours, Class of '61, accepts the news easily.

Contribute? I remember that we picketed President Dickey's house to protest having to wear ties at Great Issues. My friend recalls that members of the class. sat down on Wheelock Street, blocking vehicles trying to truck along Route 10. Unfortunately, he forgets why we did this.

Then he reminds me of the Thayer food riot. Details momentarily engulf us: how to throw mashed potatoes; how much damage the College assessed us; how students away for the weekend had lent their dining cards to others and, being traced through the cards collected at dinner, were trapped in their crime; how WDCR covered it live. We explain all this to our wives.

No contribution at all. We can't quite explain that to ourselves.

"Are you people asleep?" asked our class secretary seven years ago. Well supplied with notices of our marriages, children, and promotions, he realized that he had little information about the people who began the marriages, begat the children, earned the promotions. Not much contribution there, either.

Now it is our 15th reunion (in our 16th year after graduation), and it promises to bring the sleep-walkers together. The script is already written (by Robert Benchley):

"Well, how the hell are you?"

"Great! How are you?"

"Great! How are you?"

"Great! Couldn't be better. Everything going all right?"

"Great! All right with you?"

"Great! All right with you?"

"You bet."

"That's fine! Kind of quiet around here."

"That's right! Not much like the old days."

"That's right."

"Yes, sir! That's right!"

IT isn't easy to upstage the amiable chatter of classmates lined up at the registration table, gauging each others' hairlines, waistlines, age lines, but '61 is trying. From the northern end of the green and white tent, an occasional "Keep it down!" admonishes the registerees, who look up and see a circle of talkers. They see what seems to be a bull session and drift over to listen in. What they hear doesn't sound like bull.

These classmates, many of whom haven't seen each other since graduation, are talking about themselves from a strange perspective. They are talking about their periods of unemployment, their obsessive and sometimes debilitating hobbies, the tensions which accompanied their job changes, the women they had married and divorced, and the effect of the changes on them. Compared to the crass scenario traditionally acted out at reunions, this one surprises the onlookers. Their classmates are saying their lives have been a mess: jobs, wealth, youth, wives, all squandered. And those who talk willingly have a willing audience. As many as 70 men and their wives or friends are encircled here. And the reunion hasn't even officially begun.

The discussion is being led by Tom McDonough '61, who, asked a year ago by the reunion committee what he would like to come back to, replied, "More than a lot of people drinking. If I'm going to spend three days with people, why not say something?" The committee told him to organize what he had in mind. In a subsequent class newsletter, he sent a questionnaire which did a bit of personal probing. He received only five replies, "but everyone got a sense of what we were shooting at," he will say later.

He assigned reading - Gail Sheehy's Passages: Predictable Crises of Adult Life. Sheehy, through interviews and a vast amount of reading in current psychology and sociology, addresses the problems at certain stages of life from late adolescence to 50. Life rarely turns out to be smooth. Although that may not be news, it is news that everyone has similar problems; but few are accustomed to admitting to them. The implication is that people not in touch with each other for 16 years can come together, and even be drawn together, by talking about their real selves. Most people agree that the harsh periods of life are growing experiences. Why is it so novel to discuss those experiences? Is it because we grow only when our pretenses, our public images, have been punctured, and we can scarcely face ourselves, much less others, in those vulnerable moments?

Sheehy studied people who practically define a Dartmouth class: "America's 'pacesetter group' - healthy, motivated people who either began in or have entered the middle class." This group, she says, constitutes "the carriers of our social values," the people with "the greatest number of options and least number of obstacles to choosing their lives."

McDonough opens the session, which is called "Crisis in the Mid-30s," with a few words to show his engagement with the idea of crisis. He speaks of his own life - a hitch in the Navy, another in business, another in insurance, a marriage when he thought he had found himself, a divorce when he realized his misjudgment, now a career as a psychologist.

Another class member testifies to his own hardships. McDonough speaks again, then tries to recede into the background in order not to lecture. "I've been working on that technique for a long time," he will say later. "Then I turn it over to the group."

He does that here. There is a pause. "That's the point when it all goes down the drain, or it takes off," he will explain.

The discussion takes off. The men of '61 blow their cover. They have all felt instability at various times since graduation; it has been predictable only in retrospect, for no one warned them to expect it. It is widespread, if not universal (but not everyone testifies).

A veil lifts, the veil of the traditional success story. Life is struggle, tension, discovery, self-realization. Sharing the individual stories becomes the essential contribution of the reunion. The classmates aren't asleep, by God.

The session has a quality of déjà vu. The renegade secretary who dared stir us from slumber also dared to wonder if, so many years from graduation (then nine), the class notes were sufficient to keep us together as a class. He reasoned that, with all of our accomplishments to date, we could surely think, and what we thought would make more interesting reading than job titles. He signed the column with his name, he wrote, "because it's me as a person talking, not just an anonymous editor."

He harangued the class for half a year with challenges like "What are you doing that you're proud of?" (In the issue when this appeared, the '60 secretary in the neighboring column observed that one of his own class members returned his news inquiry form "with four words on it other than his address. They were: attorney, married, two daughters.")

The '61 secretary received a few responses. One was a long letter from a classmate who recalled the "artificial miseries" of Freshman Week as the Sophomore Orientation Committee, with the tacit approval of the College, hounded us with the aim of helping us cohere as a class. The writer questioned the rationality of that approach, as it imposed brotherhood upon us and engendered "false enthusiasm" for Dartmouth. As an alumnus, he continued, he objected to "the further assumption that collegiate personalities persist mostly unchanged in thirty-year-olds." He sounded like a neo-Benchley writing to an ur-Sheehy: "An alumnus is perpetually a freshman in the eyes of a typical class secretary."

Sixty-one's untypical secretary soon resigned his post, but his bland chickens came home to roost. They were ready to talk the columns they would not write for him.

UNDER the tent this morning, the classmates are not asleep. And what they are proud of is that they know they are awake. "I felt like a lightening rod," McDonough will say later. "Everyone had the same thing on the tip of his tongue."

After the session, a classmate comes up to him and says, "You know, I never really knew you in college."

"Maybe you did," replies McDonough, who thinks of himself as having been an anxious undergraduate. "But I've changed."

McDonough thinks about a pithy summary of reunions someone once told him: At the 5th, you sit around and talk about where you're going. At the 10th, you sit around and talk about how you never went. At the 15th, you make it or break it - either you become increasingly superficial, or you decide you'll talk about what's really happening.

And about what happened. Going back 16 years, the '61s revise their own history. They speak of bad things, chiefly wasted time, wasted opportunities, and exorcise the unreal, dreamy illusions of the undergraduate days. The exercise helps root them in the present more firmly. "It was like getting new friends," says McDonough, as he thinks of the people who have spoken up, "which means a lot because they knew me back then."

There are two other sessions, one on men's consciousness and one on occupations. Each brings forth its heroes. Classmates hear from the lawyer who moved from a high-pressure law firm in New York City to California, where he works four days a week in a drastically different but vastly more satisfying lifestyle. ("It's right for me, maybe not for you," he says.) His story is his litany, and from the way he repeats it, it is clear that he is still reacting to the enormity of the change. He seems to appreciate and use advantageously the sympathetic ears of his classmates.

The only formal aspect to any of the sessions (all run by classmates, the College standing aside) is a questionnaire on occupations, which had been inserted in the registration packet. Most like their jobs. But two-thirds of the respondents note that the greatest problem with their jobs is excessive pressure and tension. Asked how they have dealt or will deal with the problem, many reply that they intend "to assert my own interests more." But the striking replies are the ones which say "panic" or "you tell me."

These cries for help may have been written by the ones who stand up during the session and say of their jobs, "I want to get out."

Their feeling is not unique, and perhaps they are bolstered by others who rise and say, "I got out."

How genuine and thorough, rather than self-appeasing and self- justifying, are the testimonies which the classmates give? There are limits, which become obvious even as the stories are told. No one who changed vocations confesses to still being a failure. A classmate who testifies at the crisis session seems to have weathered his storms; he sounds healthy, positive. A few minutes later, his wife says, "He's still a male chauvinist." Some parts of him may still be dozing.

As the tales of personal catastrophe accumulate, a cartoon by Charles Addams perversely comes to mind. It shows a group of derelicts, wearing their class button, unshaven, uncombed, their eyes suspicious, withdrawn, glazed, or fixated, coats drawn up protectively, cigarettes dangling limply from their lips - undeniably down-and-outers. They are slumped on the portico of a college building under a large sign welcoming their class. One is saying, "I thought it was me, but maybe the school's no damn good."

Surely those who have chosen to attend the reunion are generally feeling good about themselves and, even though eager to tell their own stories, they in some deep way retain the self-confidence and, in some cases, arrogance of their undergraduate days. "What if life is giving you everything you want?" asks a Dartmouth wife at the crisis session. Everyone laughs. No one can tell whether she is able to look life straight in the eye or whether she has missed the point.

There are those who don't relate to what they hear because they have never had fa crisis. And there are those who don't like what they see. The three sessions make them angry. Some come up to McDonough and throw the word crisis back at him. "Why do you have to be so heavy?" they ask, and go off to play tennis.

But McDonough isn't done. He would like the class to hold a follow-up weekend and have the College arrange for a faculty member to guide the class by suggesting additional reading and helping to make personal evaluation systems. He also would like classmates to send in biographical and personal information to be collected in a class book, which would provide a base for expanding what the reunion began.

HE makes this suggestion unaware that the 25-year class, '52, did put out a book, Miles to go.... Each class member was invited to write his own "class notes" column, 250 words long, featuring himself. The Class of '52 ought to have been apathetic (according to the word for the fifties), lock-stepping its way through life, too late for the consciousness-raising of the 1970s but, in its affluence, smugly unworried about keeping troubles under wraps.

And because of one incident, this is how many '61s view the Class of 1952. In a question-and-answer session with President John Kemeny, a '52 asks why alumni don't have more say in formulating College policy. After all, the questioner asks, don't alumni have a lot of experience? He himself has been "moderately successful" in business, and many of his classmates have been even more successful, and those achievements ought to add up to some measure of wisdom, he says.

Kemeny, who startles many '61s with his peremptory reply, accuses the alumnus of not trusting in representative government. He mentions the Alumni Council, alumni polls, and other ways by which the College taps alumni wisdom. The alumnus appears as a fifties stereotype to some '61s - he is successful and he assumes that his success is a credential for commenting on education at Dartmouth. But what about the shocks of life that the '61s have been discussing? Here's a guy who doesn't seem to have suffered them. Can a life pattern of the fifties give advice to the undergraduates of the seventies?

The alumnus, however, is not fully representative, according to the class year-book. True, many class members succumb fully to the expected mode, treating their lives like balance sheets to stockholders. Many give the impression that job changes were, if not planned, always salubrious. Many sweep divorces and other unhappy recollections under the rug and say so. Many say that Dartmouth made a lasting, positive impression without particularly indicating how. Although a few Republicans are red-faced about Watergate, the national issues in their time - the Korean War (almost all were drafted), McCarthyism, Vietnam, assassinations, the 1960s, recessions - seem to have occurred on another planet.

Conversely, many feel that the little things that have made up their days are not worth commenting on (even though the poem from which the yearbook gets its title makes an apparently trivial event a significant juncture in the driver's life).

On the other hand, many '52s wrestle with the form and obviously want to say that some events had meant something to them, had changed them, had brought them close to life. Sometimes, doing so embarrasses them. They overwrite or write arcanely (curiously, several of this kind are from professional or experienced writers). They speak in the third person or put their words in quotations for distance. Some who surely know better try to hide: A chairman of an English department has his wife ghost his essay; a history professor tells us almost nothing of his own history; a psychoanalyst announces his occupation, and his entire entry is maybe ten per cent of his space allotment. (Yet they responded. Not everyone did.)

Others must have fascinating stories, some of which lie just beneath the telling of the events. One has recently closed his law practice and sailed a 42-foot boat up and down the California coast and then to Hawaii; another was lost in a snowstorm on a mountain; others suffered family deaths which clearly changed their direction. ("I need a new start," says one who is also unemployed.) One has a Dartmouth daughter who avoids him when he comes to campus because of the way he acts with his cronies. A few seem to hate Dartmouth and say they learned nothing here.

THOSE who might have enjoyed the '61 sessions seem to have imposed restraint on themselves. For one, a divorce is "best forgotten." One uses the word "struggle" three times, his main achievement being the financial growth of the company which employs him. Many state that their children are in turbulent growth stages, as if they themselves are now exempt from crises. Many admit, usually with surprise, that their life shows no plan. Another isn't sure his classmates care: "What was learned? Little of use to you."

The poet who contributed the title of the yearbook wrote another poem, "The Road Not Taken," which seems to stand behind many of the entries (it is mentioned at least twice). As Professor John Finch used to explain, the poem is not about taking a less common passage or path in life, but how, when a route leads the follower to a pleasurable destination, the follower looks back on the choice, made in blindness, and innocently deludes himself into thinking that he always had his wits about him.

An individual's biography, especially when written by himself, will usually affirm that insight. The times are urging us to break away from it. The Class of '61, sometimes viewed as a transition class between the so-called apathetic '50s and the self-reflective '6os, woke up at least once.

Marshall Ledger '61 is the staff writer forthe Pennsylvania Gazette. "When peopleat reunion asked me what I did and I toldthem I write for Penn's alumni magazine,"he says, "they stared as if they didn't comprehendme."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureScience and Technology Under Siege

September | October 1977 By Thomas Laaspere -

Feature

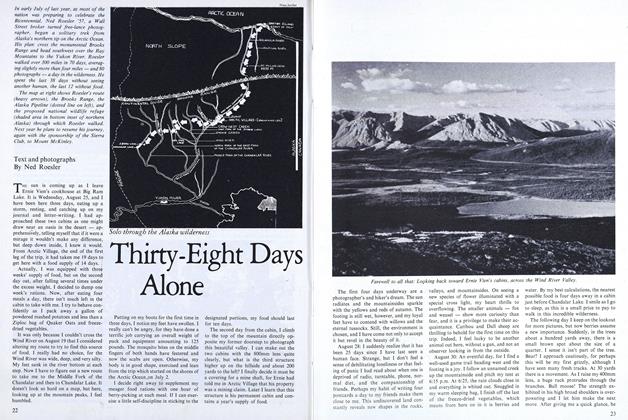

FeatureThirty-Eight Days Alone

September | October 1977 By Ned Roesler -

Feature

FeatureWorlds Together

September | October 1977 -

Article

ArticleFanciers

September | October 1977 By BRAD HILLS '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1927

September | October 1977 By ERWIN B. PADDOCK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

September | October 1977 By ROBERT W. HARVEY, STEVE WINSHIP

Marshall Ledger

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Friends' Best Friend

JANUARY 1964 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

JULY 1973 -

Feature

FeaturePursuing Sleep

February 1976 By B.K. THORNE, NANCY DECATO -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Defense on the Economy

May 1961 By GEORGE E. LENT, PROFESSOR -

Feature

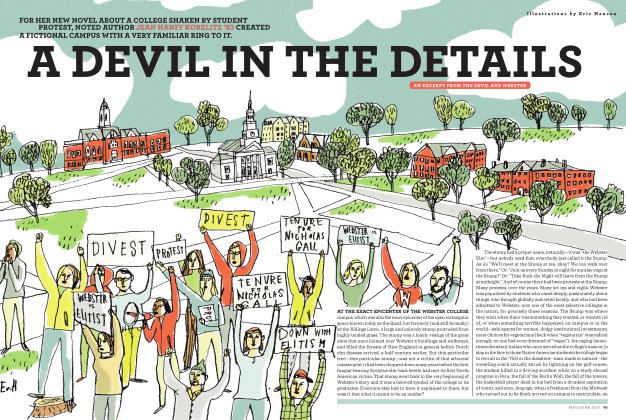

FeatureA Devil in the Details

MAY | JUNE 2017 By Jean Hanff Korelitz ’83 -

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1977 By MARY ROSS