Notes on travelers who tread the paths that angels fear, and the road signs they post along the way.

June 1979 R. H. RNotes on travelers who tread the paths that angels fear, and the road signs they post along the way. R. H. R June 1979

PROFESSIONAL writers who write books telling other writers how to write must surely have a great deal of Don Quixote in them. They dream the impossible dream. For each of them is bound to know in the heart's core that the ancient principle still holds: no one can teach anyone else how to write. Not, that is, in any meaningful sense. To be sure, grammatical correctness the right and the wrong way of say- ing something - that can be taught. But the real problem is not how to write correctly; it is how to write cleanly, effectively, with precision, economy, power. In a word, style. That's what can't be taught.

Yet the Quixotes keep trying. And long may they prosper! Mutilated by the writer of advertising copy, despoiled by the bureaucrat, smothered beneath the creeping ooze of business and scientific jargon, starved by the benign neglect of almost everyone, our language has fallen on parlous times. It needs all the physicians it can attract, especially those willing to tack up a few quarantine signs around some of the more obvious pest holes. Contagious horrors abound. Here's one of them: "It is believed that with the parameters that have been imposed by your management, a viable solution may be hard to find. If we are to impact the consumer to the optimum, further interface with your management may be the most meaningful step we can take." If that lump of sodden jargon reads intelligibly to you, you're in trouble.

A particularly flagrant example of how not to write, it comes from a new manual by Ken Roman '52 and Joel Raphaelson: How to WriteBetter (New York, Ogilvy & Mather, 1979. 52 pp. Softcover. $5.00). It is a wise little book, full of common sense and wit, pithy, short on generalized exhortation but long on instructive example. It is not meant to compete with Strunk and White; it is not a book for all writers nor for all seasons. Rather it is aimed at those business executives who, though they retain the will, may not quite know the way to communicate effectively in writing with their colleagues and clients. The subtitle reads: "The Ogilvy & Mather guide to effective memos, letters, reports, plans and strategies."

Clearly, Roman knows his subject. He had better. As managing, director of Ogilvy & Mather, a New York advertising firm, he must make his living by his skill with language. On the face of it one could surmise that the book began perhaps as an in-house manual aimed at eliciting more effective writing from the company's own executives; perhaps it was intended for general distribution from the start. It matters very little, for now that the light is out from under Ogilvy & Mather's bushel, it is quite capable of illuminating the murky corners of many another corporate headquarters piled high with ill-organized reports, prolix interoffice memoranda, and slushy letters.

For instance, take a simple little thing like Roman's "secret" no. 5 (one of his "20 secrets of good writing"): "Make your writing vigorous and direct. Whenever possible use active verbs, and avoid the passive voice." Now there's a first principle if ever there was one! It isn't for nothing that the passive voice is the favorite locution of bureaucrats: it's a convenient device for avoiding responsibility for one's own statement. "It is recommended that. ..." Recast that one in the active voice and the writer can no longer hide behind that impersonal "it"; willy nilly, he must supply a personal subject for his verb. "I recommend that ... The Managing Director recommends that. ..." The passive voice has its uses, but the active avoids weaseling, it is direct, it is vigorous. It is recommended that all memo writers fasten secret no. 5 to their hearts. Hopefully, it will save them from perdition.

So there's another one! Consider secret no. 15: "Be brief, simple and natural. ... Don't write 'hopefully' when you mean 'I hope that.' 'Hopefully' means 'in a hopeful manner.' Its common use annoys a great many literate people."

Brevity, simplicity, naturalness: such easy nouns to write, such hard conditions to achieve when pencil actually comes to paper. Hard but not impossible, because they can be achieved if the writer is willing to work at his job. Nowhere is the work harder than at the beginning and the end of the writing process. Thus Roman's secret no. 2: "Know where you're going. ... Start with an outline to organize your argument." That's the work at the beginning. And then secret no. 19: "Never be content with your first draft. Rewrite, with an eye toward simplifying and clarifying. Rearrange. Revise. Above all, cut." That's the work at the end.

Beginning, middle, or end, writing well requires the hardest work of all: it requires us to think. Roman says so himself, but for emphasis I will take it upon myself to add a secret of my own to Roman's list of 20. It's an open secret: Before you can write effectively you must first have thought well. If you haven't thought it through, the chances are you won't write it clearly. And perhaps I'll risk a second one — though I set it down ruefully. Open secret no. 2: In spite of the rigor of your thought, your outlines, revisions, cutting, all too often that idea you had in your head will escape those words you write on the paper. There is no such thing as perfect writing; there is only better or worse. E. B. White says it best: "When you say something, make sure you have said it. The changes of your having said it are only fair."

On the subject of writing, indeed, E. B. White says most things best. The famous Strunk and White, The Elements of Style, now in a newly revised third edition (New York, Macmillan, 1979. Softcover. $1.95), is quite simply the finest book on writing in our century. Close — very close — to it is The Golden Book onWriting by the late David Lambuth of Dartmouth's English Department, the most recent edition of which (New York, Viking, 1963) contains a foreword by Budd Schulberg '36. But it is the influence of Strunk and White which seems imprinted on nearly every page of Roman and Raphaelson.

Ironically, E. B. White directs some of his keenest barbs at those who, like Roman and Raphaelson, ply the craft of advertising. The language of advertising, he writes, "with its infractions of grammatical rules and its crossbreeding of the parts of speech ... profoundly influences the tongues and pens of children and adults. ... Your cigarette tastes good like a cigarette should. And, like the mansays, you will want to try one. You will also, in all probability, want to try writing that way, using that language. You do so at your peril, for it is the language of mutilation."

Such language has no place "in ordinary composition, whose purpose is to engage, not paralyze, the reader's senses. Buy the goldplated faucets if you will, but do not accessorize your prose. To use language well, do not begin by hacking it to bits; accept the whole body of it, cherish its classic form, its variety, and its richness."

In their own book Roman and Raphaelson choose to overlook such strictures. And rightly so, for they do not, after all, set out to tell us how to write ad copy (which is what White excoriates); that art is reserved to professionals of quite a different order. They set out only to show us how to write straightforward business prose, and in the end their advice precisely coordinates with White's: simplify, write naturally, be clear, revise, rewrite.

Nevertheless, just the faintest whiff of irony persists. From the very epicenter of the temple of Mammon the Mutilator, two advertising men launch their quest for the grail of the pellucid inter-office memo. (White's rule no. 18: "Use figures of speech sparingly. ... When you use a metaphor, do not mix it up.")

Fairness demands one further observation. White applies his lash even more vigorously to us who write for college alumni magazines than to those who write ad copy. Archetypal practitioners of "the breezy style," he calls us. "Open any alumni magazine, turn to the class notes," he claims, "and you are quite likely to encounter old Spontaneous Me at work — an aging collegian who writes something like this: "Well, chums, here I am again with my bagful of dirt about your disorderly classmates, after spending a helluva weekend in N'Yawk trying to view the Columbia game from behind two bumbershoots and a glazed cornea. And speaking of news, howzabout tossing a few chirce nuggets my way?"

That writer can claim a record of sorts. In a mere two sentences he has managed, White says, "to commit most of the unpardonable sins: he obviously has nothing to say, he is showing off and directing the attention of the reader to himself, he is using slang with neither provocation nor ingenuity, he adopts a patronizing air ..., he is tasteless, humorless (though full of fun), dull, and empty. He has not done his work."

Surely no writer for this alumni magazine could be guilty of such abominations! Quick, let's all turn back to our class notes and find out. Or need we turn only as far as The College section — or the Reviews section?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature'We will all make whoopee'

June 1979 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

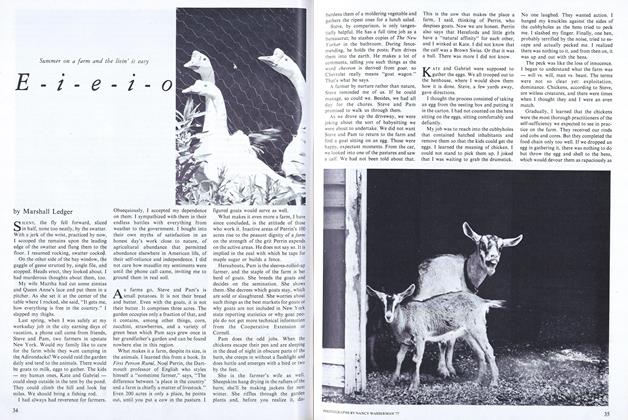

FeatureE – i – e – i – o

June 1979 By Marshall Ledger -

Feature

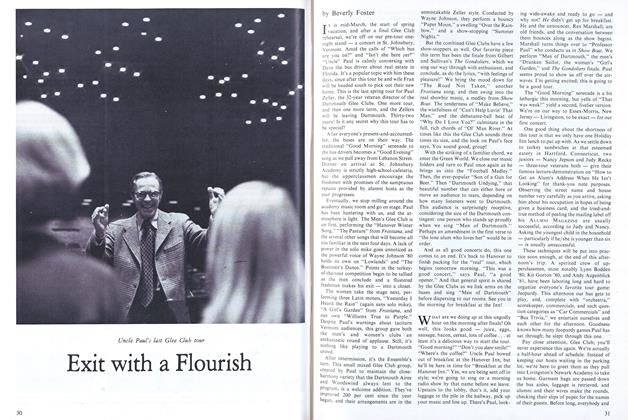

FeatureExit with a Flourish

June 1979 By Beverly Foster -

Feature

FeatureEncouraging growth, affirming the educational process

June 1979 By Robert Kilmarx -

Article

ArticleCommencement

June 1979 By James L. Farley -

Article

Article'Radical' with a Cause

June 1979 By Tim Taylor

Books

-

Books

BooksA DARTMOUTH NOTABLE

NOVEMBER 1931 -

Books

BooksAT DADDY'S OFFICE

November 1946 By Alene P. Widmayer -

Books

BooksWILLIAM E. CHANDLER, REPUBLICAN

February 1941 By CLAUDE N. FUESS -

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

December 1934 By Harold G. Rugg -

Books

BooksTHEODORE SEDGWICK, FEDERALIST: A POLITICAL PORTRAIT.

JULY 1965 By JERE R. DANIELL II '55 -

Books

BooksLA VIERGE AUX YEUX DE FEU

June 1933 By William A. Eddy