I would like to address the subjects treated in "A winter of discontent . . which appeared in the April issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. I write as a Dartmouth wife ('24), as a fouryear Dartmouth Alumni College "graduate," and as a professional woman who began her career in the mid-twenties when the going was rougher for women than it is today.

I would like to take aside those "Women at Dartmouth" (apparently a small minority of the women enrolled at the College) and ask them to take a second look at their behavior. Aren't they embarrassed to see how they allowed themselves to be "had" by Playboy magazine and by The Dartmouth? Had the women simply ignored the original Playboy offer, the whole thing would have fallen like a lead balloon and it is Playboy which would have looked foolish.

The women would have exhibited their moral and intellectual superiority and would, as the old saying goes, have come out smelling like roses.

While we are at it, did these women have anything to do with drafting that statement proclaiming a goal as "sex-blind admissions with adequate recruiting to bring up the number of female applicants ...?"

Yes, Virginias, you do seem to want it both ways.

What's wrong with the word "coed"? Webster's dictionary lists it as an acceptable word, defining it as a female student. No matter how these women feel about it, they are females as well as students. Is it so bad to wear a female body? Is there a hint of dissatisfaction with having to face life as a female? Do these "Women at Dartmouth" unknowingly for a unisex society? A sexless society, then a classless one?

Leaving what appear to be the women's self-inflicted wounds, let's turn to the problems of the blacks. Having been white and female for nearly 75 years, I recognize that I can't fully understand the problems of the black male; but doesn't he (as well as she) want the things everyone else wants — a good house, good food, good clothing, good education, career opportunity, plus dignity and respect from other human beings of whatever race?

Here I do have some personal experience. Working for some time for the federal government, which is perhaps more color blind than other employers, I have seen blacks in good jobs. I myself was deputy for several years to a black man, an officer in the U.S. foreign service, who, with his wife and daughter and sonin-law and grandchildren, became a close friend of ours. We frequently visited in each other's homes. At their house we met ambassadors, a college president, and the brother of a former president of the United States.

Through the news media I have seen evidence of other black Americans who have achieved financial, social, and political success. On the other hand, I have had personal contact with blacks whose abrasive personalities, whose "demands" for acceptance, often way beyond their abilities, have denied them the very things they sought. They couldn't remember that you don't catch flies with vinegar.

I didn't see at Dartmouth the ice sculpture graveyard or the black coffin which was a part of a demonstration against charged complicity with apartheid. Have any of the Dartmouth protestors been to South Africa? Or are they depending upon second-hand information as am I when I quote: "In the case of United States corporations, which have 350 subsidiaries in South Africa employing 250,000 blacks, the pressures have taken the form of the Sullivan code, a Washington-backed pledge prepared two years ago by the Rev. Leon H. Sullivan, a member of the General Motors board of directors, that commits signatories to accept representative black labor groups and to root out racial discrimination in all other aspects of employment" (New York Times, May 6, 1979).

If the president of the Afro-American Society found "Dartmouth a living hell for black students" (surely an exaggerated statement!), why did he remain there?

Possibly more incomprehensible to me is the protest of the Native Americans, but here I do admit that I may be guilty of harboring a romanticized, and loving, notion of the American Indian and I am willing to try to understand otherwise. Incidentally, my husband questions the statement that the Indian mascot symbol was created in the twenties. So far as he can remember, it was already a part of the institution when he and his brother enrolled at Dartmouth in 1920.

Has there, by the way, been any attempt by Native Americans to change the name of the Washington Redskins or of the Atlanta Braves?

With 42 Native Americans now at 'Dartmouth, they have the opportunity of increasing 200-fold the Indian (pardon my use of the word at this point) alumni from the 20 which was claimed between 1769 and 1971.

Considering the feelings of those Native Americans (would they object to just the word "Natives"?), the two students who dressed in feathers and skated onto the hockey rink showed poor judgment. But here, as with the women and Playboy magazine, the Indian students could have ignored, or laughed off, the event. The participating students may have deserved chastisement but not suspension. (By the way, whatever happened to "streakers"?)

The person who actually deserved suspension, I would suggest, was the one who said, and I quote from the ALUMNI MAGAZINE account, that President Kemeny's action reinstating the suspended students was a "slap in the face for the Native American community" and "the most heinous and racist act any president of Dartmouth college has ever committed."

Oh, come now! Such verbal abuse only incriminates the accuser, not the accused.

Throughout the ALUMNI MAGAZINE article are quotations so intemperate as to be simply juvenile and unbelievably attributable to evenminded students intent upon acquiring a higher education rather than seeking to remake the institution which they have chosen to attend.

President Kemeny must feel that at times his job is that of a baby sitter. Perhaps that is part of a college's responsibility teaching juveniles to become responsible adults.

We find ourselves pondering how much protest, how many demonstrations, how inciting the manifestos which a college administration must feel itself obligated to consider and give attention to as part of a healthy college experience before the point is reached where it becomes nothing less than a retreat before pre-meditated, well-planned, and timely triggered pressure tactics, and the college's ultimate submission to the tyranny of organized minorities?

Doris Bowers worked with the USIA in Washington.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature'We will all make whoopee'

June 1979 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

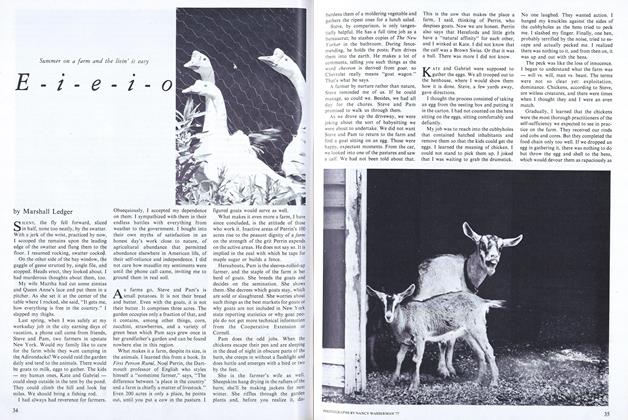

FeatureE – i – e – i – o

June 1979 By Marshall Ledger -

Feature

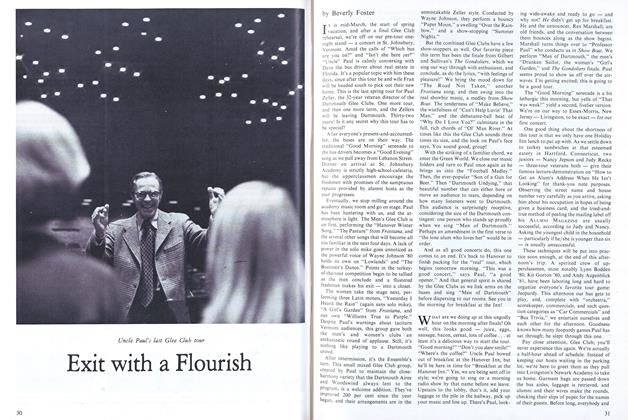

FeatureExit with a Flourish

June 1979 By Beverly Foster -

Feature

FeatureEncouraging growth, affirming the educational process

June 1979 By Robert Kilmarx -

Article

ArticleCommencement

June 1979 By James L. Farley -

Article

Article'Radical' with a Cause

June 1979 By Tim Taylor

Article

-

Article

ArticleTWO DARTMOUTH PHYSICIANS

November, 1916 -

Article

ArticleNOTED ARCTIC EXPLORER GIVES BOOKS TO THE OUTING CLUB

April 1921 -

Article

ArticleGeology Newsletter

February 1954 -

Article

ArticleJudd Scholarship Fund

MARCH 1973 -

Article

ArticleLurch and the Munchkins

October 1976 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleFREE HEALTH SERVICE

April 1937 By William B. Rotch ’37