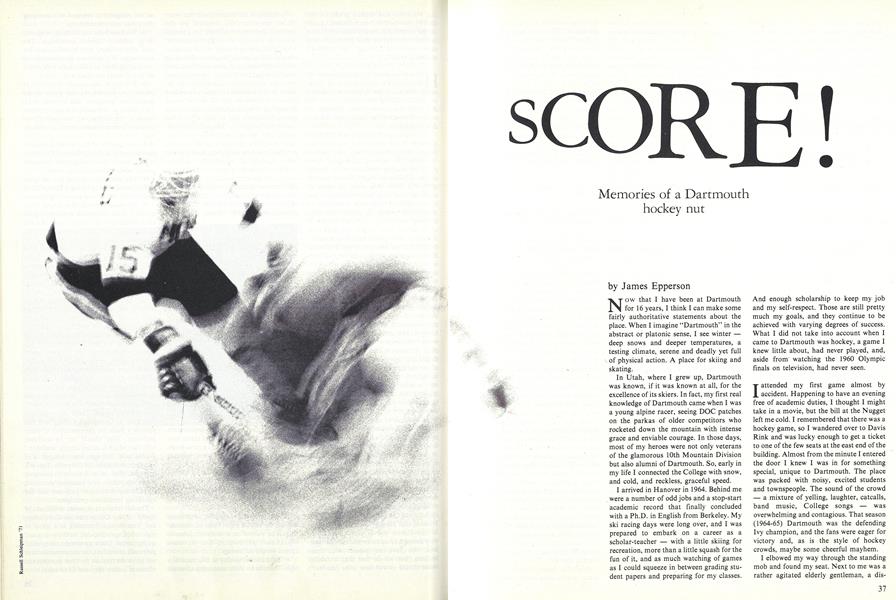

Memories of a Dartmouth hockey nut

Now that I have been at Dartmouth for 16 years, I think I can make some fairly authoritative statements about the place. When I imagine "Dartmouth" in the abstract or platonic sense, I see winter deep snows and deeper temperatures, a testing climate, serene and deadly yet full of physical action. A place for skiing and skating.

In Utah, where I grew up, Dartmouth was known, if it was known at all, for the excellence of its skiers. In fact, my first real knowledge of Dartmouth came when I was a young alpine racer, seeing DOC patches on the parkas of older competitors who rocketed down the mountain with intense grace and enviable courage. In those days, most of my heroes were not only veterans of the glamorous 10th Mountain Division but also alumni of Dartmouth. So, early in my life I connected the College with snow, and cold, and reckless, graceful speed.

I arrived in Hanover in 1964. Behind me were a number of odd jobs and a stop-start academic record that finally concluded with a Ph.D. in English from Berkeley. My ski racing days were long over, and I was prepared to embark on a career as a scholar-teacher with a little skiing for recreation, more than a little squash for the fun of it, and as much watching of games as I could squeeze in between grading student papers and preparing for my classes. And enough scholarship to keep my job and my self-respect. Those are still pretty much my goals, and they continue to be achieved with varying degrees of success. What I did not take into account when I came to Dartmouth was hockey, a game I knew little about, had never played, and, aside from watching the 1960 Olympic finals on television, had never seen.

1 attended my first game almost by accident. Happening to have an evening free of academic duties, I thought I might take in a movie, but the bill at the Nugget left me cold. I remembered that there was a hockey game, so I wandered over to Davis Rink and was lucky enough to get a ticket to one of the few seats at the east end of the building. Almost from the minute I entered the door I knew I was in for something special, unique to Dartmouth. The place was packed with noisy, excited students and townspeople. The sound of the crowd a mixture of yelling, laughter, catcalls, band music, College songs was overwhelming and contagious. That season (1964-65) Dartmouth was the defending Ivy champion, and the fans were eager for victory and, as is the style of hockey crowds, maybe some cheerful mayhem.

I elbowed my way through the standing mob and found my seat. Next to me was a rather agitated elderly gentleman, a distinguished dude dressed in a fur-collared coat and obviously an alumnus. He sang the College songs with lusty vigor, and shouted encouragement to the Dartmouth skaters who circled the rink in what I have since come to recognize as a standard pregame exercise. I will have more to say about this elegant old fellow in a minute.

I don't remember much about that first game. I am pretty sure that Dartmouth won, that our opponent was one of the Boston teams (Harvard, BU, BC, Northeastern), and that Chip Hayes, Chuck Zeh, and Dean Matthews played a helluva game. Despite my ignorance of the rules and the fine points of the game, not knowing a poke check from a back check or a slap shot from a wrist shot, that first taste of Dartmouth hockey had me hooked.

Aside from occasional illness and two seasons spent in London, I have not missed a home game since that contest in the winter of 1965. Over the years I have probably spent several hundred hours watching hockey and a few hundred more just thinking about it. What puzzles me is the hold, the death-grip really, that hockey seems to have on my mind and imagination. Why am I, an English professor, also a hockey nut? What makes me leave a warm house when it's well below zero and make my way across a frozen landscape to a hockey game? Why have I more than once driven alone to Boston and back inthe same night to see Dartmouth beat the bejezzus out of Harvard?

A solemn psychiatrist might answer these questions by referring to my sublimated desire for violence, my unfortunate male tendency to experience vicariously emotions of aggression and triumph, and so on. Well, the hell with that. I take some comfort in knowing that men and women are hockey nuts. My gentle and compassionate wife, a sturdy defender of endangered species, a mother now transformed into a liberated librarian, is an avid and very noisy rooter for the Big Green teams. She knows the names and numbers of all the players, and has more than once baked a ton of cookies and delivered them personally to the team office. Her spirits rise and fall with the team's fortunes; like me, she is a poor loser and an arrogant winner.

My passion for the game is, I am glad to say, shared by a number of my faculty colleagues. A very distinguished mathematician sits behind me at the games and yells to beat the band, his Dutch accent giving a nice cosmopolitan flavor to bellicose shouts of "Hit 'em! hit 'em!" Frank Smallwood '5l, the Orvil Dryfoos Professor of Public Affairs, has for many years sat next to me and is a close student of the game, a reader of statistics and an analyst of the team's successes and failures. Still, his dementia is not as acute as mine. He did not, for instance, make the trip to the Boston Garden last March to see the Big Green play so brilliantly against BU in the ECAC semi-finals. He did, however, listen to the radio broadcast, and made a tape of the finals against the University of New Hampshire, just so we could renew the memory of that stirring contest at some future date.

Hockey nuts really come in all shapes and sizes, male and female, young and old, gentle and rough, from the bookish scholar to the weather-toughened local carpenter. What attracts the loyalty and passion of these fans is the game itself and not necessarily its much publicized violence. Anyone who really knows will tell you that, of course, violence (more genteely, "body contact") is a part of the action, but a very small part. And the best games are usually the ones played with the fewest number of penalties. The other kind, and the least satisfying, are contemptuously termed "chippy" games, in which an inept or desperate team tries to win with elbows, blind-side checks, high sticks, and sheer thick-headed brutality. Such travesties of the art of hockey are quickly forgotten. But contests between skillful combatants, swift skaters and dazzling puck handlers, intelligent playmakers and rugged but elusive defensemen, deadly shotmakers and agile goalies these games live forever in the memory of the hockey nut, and can instantly be recalled in the middle of July. It is such memories, I believe, that keep me coming back for more, and then more, hockey.

THERE are certain characteristic patterns of a game of hockey; among my favorites are the rush, the flurry around the net, and the dramatic solo dash. Nothing lifts a hockey fan higher than the breakout and the subsequent rush, a maneuver performed with great skill by our 1978-79 Ivy championship team.

First, the breakout: With the puck in the Dartmouth zone and our opponents trying to score, one of our superb defensemen, either Bob Grant, Dennis Hughes, or Chris Sosnowski, would battle for the puck and then pass it out to one of the three skaters on the front line. Instantly the movement of the action is reversed. Simultaneously the center and the two wings, probably Ross Brownridge along with Dennis Murphy and Donny O'Brien, would start the rush, flying down the ice toward the enemy goal, spread out in a line across the rink, moving the puck between them with stunning accuracy and thrilling grace. Onthe attack! The crowd begins to roar. The players reach and cross the blue line, penetrating the opponents' zone. Brownridge, carrying the puck, skates out of the center, the wing heads for the goal, Brownridge passes in, the wing shoots, and ....

GOAL! (if everything works as it should). Whether or not Dartmouth scores, the excitment of the rush never diminishes. The grace, the speed, the determination of the players and the anticipation of the possibilities add up to a superb and, I would argue, aesthetic moment of intense pleasure.

What I call the flurry around the goal is almost too intense an experience.

Sometimes the elaborate patterns of the game break down, usually after the goalie has blocked a shot and the puck is loose in front of the net. Then the players from both teams converge around the goal mouth, sticks and elbows flying in a boiling mass of energy. The excitment of the moment is heart-stopping. Get that puck! clear it! (if defending) shoot it! (if attacking). The tension is unbearable.

The most memorable flurry for me occurred in the last home game of the 1976 season. Brown and Dartmouth had played a solid and splendid game, but with seconds to go, Brown led by a single goal. While the big timer over the ice ticked away, we managed to get the puck in the Brown end. There was a shot on goal, a flurry, another shot, another flurry the crowd was on its feet, howling, bellowing, crying. With one, one, second to go, Kevin Johnson found the puck and rammed it home to tie the game. Dartmouth won it in overtime, almost an anticlimax.

The solo dash is perhaps the most dramatic performance in hockey or any other game. It happens when a single player gets the puck in his own end, then miraculously weaves his way through his own and the defending teams, finally to face the goalie head on and, bringing the whole magnificent performance to perfection, fires the puck into the net. When these rare moments occur, the crowd,at first is silent, holding its collective breath, then murmuring as the skater nears the goal. If he scores, the shout that follows is explosive, unanimous, and deafening, a spontaneous release of joy and admiration that brings us all to .our feet, hollering. There is nothing like it.

Over the years, Dartmouth has had some memorable solo dashers: Dean Matthews, Ken Davidson, Mike Turner, and, currently, Ross Brownridge. I will never forget how could anyone forget? a dash that Brownridge tried last March in the ECAC finals against UNH in the Boston Garden. With the score tied, 2-2, near the end of a hard-fought, cleanly contested game, Roscoe stole the puck at midice, then started for the UNH goal. Through some magic of his own making, he eluded two converging Wildcat wings, faked out the scrambling defensemen, then all alone flew straight in on the crouching goalie. A score for Dartmouth at this stage of the game would almost certainly mean victory and the championship. What a chance! About ten feet out, milliseconds before he was set to shoot, the puck took a little hop off the soft Garden ice. Momentarily he lost control; the goalie lunged full stretch with his stick, deflected the puck ever so slightly, and Brownridge never really got the shot away. The game whirled on, with UNH winning it on a slap shot from the blue line, a dipping, wicked screamer that our goalie, Bob Gaudet, never had a chance at. Fate. Luck. Skill. Glory. Defeat. Our team later had sweet revenge at the NCAA championships in Detroit when they walloped UNH, 7-3, to place third in the nation.

THESE are fine memories, but at Dartmouth, the great tradition of hockey gives me almost as much pleasure as the game itself. I first understood the meaning and depth of this tradition when I attended the retirement festivities for that great Dartmouth coach, one of four Dartmouth players in the Hockey Hall of Fame, Eddie Jeremiah '3O. The event took place at the end of Jerry's last season as coach, the late winter of 1967. After only three years of watching hockey, I was so besotted with, the game that I got a ticket to the lunch to be given in Jerry's honor. It was some lunch.

The room, Alumni Hall, was packed with former players from the three decades of Jerry's career, mostly large, ruddy, and robust characters with loud voices and hearty manners. By the time we sat down, nearly everyone was slightly oiled, nicely convivial, and a good deal more boisterous than the faculty twitter I had grown used to. As far as I could tell, I was the only member of the faculty in the place, and when I identified myself as a professor in the English Department and a non-player of the game, I was viewed with polite suspicion until it became clear to my table that I was just another hockey nut, not quite as acceptable as an ex-player, but not contemptible either. The lunch was fun raucous, earthy, and anecdotal. But the speeches were the best part of the event. After the introductions and so on, Snooks Kelly, the coach at BC, himself close to retirement and Jerry's long-time mighty opposite in the New England hockey wars, got up to speak. Kelly was an impressive figure, large and jovial with a wonderful red face, fleshy and creased by the years. His talk, delivered in the pungent tones of Irish Boston, was proper to the occasion: sentimental, sometimes maudlin, and sometimes very funny. But it had a macabre effect. What no one said, but everyone in attendance knew, was that Jerry was dying of cancer. Snooks' speech reminded us of that unhappy and, considering the day, discordant fact.

So when Snooks ended and Jerry got up to talk, the mood was one of subdued melancholy, funereal and confused. We should have known better. Jerry's motto for the team was (and still is) "Heads Up and Keep Fighting." And that's just what he did. For the better part of an hour, with no text, he delivered one of the best farewell speeches I have ever heard.

First he told a few jokes, slightly blue and very, very funny. Then he said some good words for the College, the Athletic Council, and assembled dignitaries. With that out of the way, he gazed around the room, then stopped. He pointed to one of his former charges, called him by name, asked after the wife and kids whose names he also seemed to know and then told some outrageous story of how that player had bungled a play in a particular game or had failed to make the bus or train when the team was traveling. Glancing from table to table, he managed to recall something about nearly every hockey alumnus in the room. The crowd loved it. He was still the Coach, still cheerful, still full of rough good nature. As he spoke, we forgot that before us was a man terminally ill with cancer (Jerry would die before summer), but we were reminded of his courage, toughness, and spirit, those qualities he inspired in the dozens of Dartmouth players he had coached over the years. It was a moving experience for me. It made me think of time, mortality, and tradition, but it also made me think about my role and responsibility as a teacher (a kind of coach) and the relationships I hoped to have with my students, past, present, and future.

I know now that I caught some of the hockey tradition that is special to Dartmouth at that first game I watched by accident. You may recall the elderly fan who sat next to me. Before the game started, he turned and asked a favor. "If I get too excited," he told me, "make me sit and calm down. The doctor says I get too agitated at these games. It's bad for my ticker." A little nervously I promised to do as he asked. The action was hardly underway when my neighbor leaped to his feet, shouting and waving his arms and dancing rapidly in place on the tips of his toes, his face red with effort. I tugged at his coat. He ignored my tuggings. I pulled some more, harder, then he looked down and batted my hand away. I gave up and resigned myself, as my neighbor had, as we all must, to the inevitability of death. We both survived the game, but I have not seen that old fellow since. I understand now the intensity of his participation. He was, as I have become, a hockey nut. Maybe he took his doctor's advice and stayed away from such fatal pleasures as the rush, the flurry, and the solo dash. Frankly, I hope not. I like to think of that elegant gent, swathed in his fur-collared coat, springing once again to his feet as the Big Green breaks out and the wings fly gloriously down the ice toward the enemy net. One last, heart-stopping rush. For a hockey nut, that's not a bad way to go.

Professor Epperson teaches the modernAmerican novel, Shakespeare, and hasspecial interest in King Lear. He has beenacademic director of Alumni College andwas at the center of last year's debate onfraternities. In the spring he served as anadviser to the "Indian" skaters during disciplinaryhearings on that incident.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDrinking

January | February 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureLiberal Arts, yes 'Core of Knowledge,' no Changing the Calendar, maybe

January | February 1980 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureThey Don't Even Filch the Silver Here

January | February 1980 By Steve Taylor -

Article

ArticleA Matter of Directness

January | February 1980 By Beth Ann Baron '80 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

January | February 1980 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR. -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January | February 1980 By Beth Ann Baron '80, Michael Colacchio '80

Features

-

Feature

FeatureREUNION WEEK

JULY 1973 -

Feature

FeatureWhat keeps them going? A 'Mystic Glue' Perhaps

MAY 1982 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Feature

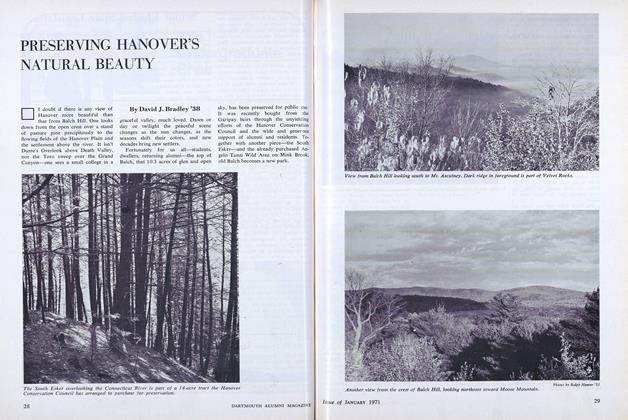

FeaturePRESERVING HANOVER'S NATURAL BEAUTY

JANUARY 1971 By David J. Bradley '38 -

Cover Story

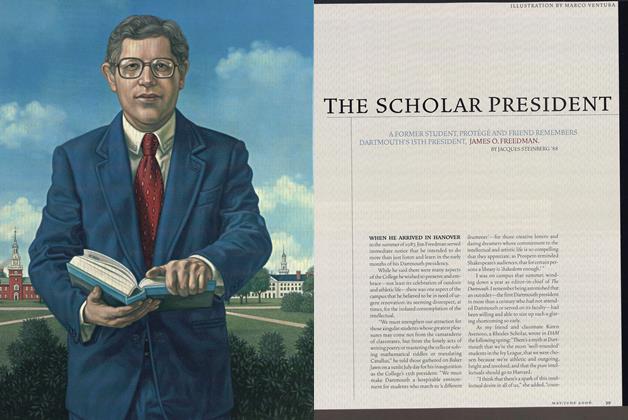

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

May/June 2006 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

JULY 1971 By JOHN L. SULLIVAN '21 -

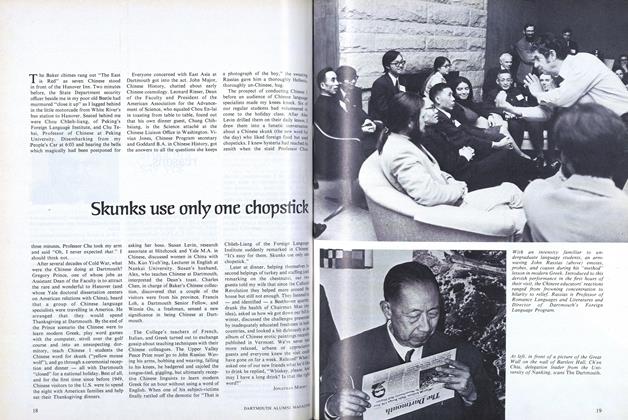

Feature

FeatureSkunks use only one chopstick

January 1974 By JONATHAN MIRSKY