You WOULD THINK THAT PEOPLE LIKE THIS GUY DIDN'T GET ELECTED LAST FALL: a career politician from a political family, with deep Washington connections. But experts say look again: In CHARLIE BASS '74 you may be seeing the future of the Republican Party.

IN January 1955, AS Perkins Bass '34 began the first of four terms as Dartmouth's Republican Congressman, the GOP began a 40 year exile as the minority party of the U.S.House of Representatives. From January 3 of that year until January 4 of this year, not one Republican had chaired a House committee or had been elected Speaker.

Then the son of Perkins, Charlie Bass '74, took New Hampshire's Second Congressional District and helped end the party's long, cold winter. The Dartmouth government major retook his father's seat, replacing a Democrat, and cast one of the 228 historic votes that made Georgia Representative Newt Gingrich Speaker.

Bass and the 72 other freshmen Republicans correctly call themselves the "Majority Makers." While the new Representative seems to fit comfortably into this overwhelmingly conservative group like many of them, he is opposed to the automaticweapons ban and in favor of most of the provisions in Gingrich's Contract with America Bass isn't in lock-step. For one thing, Bass puts himself on the pro-choice side of abortion, while most other Republican freshmen oppose abortion. And Bass is one of the few successful candidates with close ties inside the Beltway.

It is a good idea nonetheless to get to know Bass better. A self-described conservative on budget and defense issues, and a moderate on social issues, Bass (who's serving with Republican Representatives Rick White '75 of Seattle, who's also a freshman, and second-term Republican Rob Portman '78 of Cincinnati) seems to be floating on a rising tide of politics and demographics.

Harlie Bass Was Preciselythe Kind OF Insider who might have had trouble in another Congressional district. It was an election in which 21-termer Jack Brooks lost in Texas and Speaker Tom Foley got beat in Spokane, Washington, the first sitting Speaker to lose at home since 1860. But they were Democrats who had spent too much time in D.C. for the voters' taste. Bass was a Republican with such a solid New Hampshire image that he wasn't hurt by the chic Washington school he attended through the fifth grade (St.Alban's), or the business he ran in suburban Beltsville,l Maryland, or the downtown Washington real estate he still owns with his brothers, or his experience as an aide to two Congressmen.

Still, his election did not come easily. This was Bass's eighth political campaign and his second House bid. The first time he ran for the Second District seat, in 1980, he lost to Judd Gregg, who is now a U.S. Senator. Among the other primary losers was Susan McLane, a state senator and the daughter of former College Dean Lloyd "Pudge" Neidlinger.

Bass is now accustomed to competing with Dartmouth people. In the 1994 primary he beat JimBassett '78. Supporting Bassett was classmate Rob Portman, who has since won a prized seat on the House Ways and Means Committee. (Portman recently was the point man on legislation banning unfunded federal mandates.) But Bass had help of his own, including a deep reservoir of family reputation and experience. There is Perkins, who spent eight years in Washington representing the district that contains Dartmouth. (Perkins left the House for a 1962 Senate bid that he lost to Democrat Thomas McIntyre '37) There is Perkins's father, Robert, who was governor of New Hampshire from 1910 to 1912.There is Robert's grandfather, Perkins, who ran Abraham Lincoln's Presidential campaign in Shelby County, Illinois, after which Lincoln appointed him U.S. Attorney for Chicago. And the Dartmouth opponents are balanced by Dartmouth family, including Charlie's maternal grandfather, brothers Alex '73 and Bill '72, and nephew Marshal '94.

Charlie is close to his father and doesn't hide the fact. "When he's around, and before I ran for Congress, we walked every day," Charlie says. He used a photo of the two of them in all of his campaigns. "There's reasons for that," he says. "He's a former Member of Congress, he cuts a pretty good figure. He's a senior citizen. Not to mention he's my father." But Charlie also had his own political experience and he ran on it, despite the current unpopularity of politicians. He had won seats in the state house and senate, eventually losing a senate re-election bid in 1992.

That was the year Bill Clinton got elected, and Republicans nationally got bowled over. In New Hampshire, the nation's most Republican state, a Democrat, Dick Swett, was even solidly re-elected as Dartmouth's Congressman. Swett had won the seat for the Democrats in 1990 for the first time in 70 years. Bass blamed the debacle on an especially nasty Republican primary battle. So, during the 1994 primary race, the Bass strategy featured adherence to his party's Eleventh Commandment, attributed to Ronald Reagan: Thou shalt not speak ill of another Republican. Bass generally avoided first strike personal attacks on his party opponents; the harshest kind of statement came in his repeated insistence that he was the most qualified for the job of Congressman. In August of last year, for example, when there were still some ten Republicans running, Bass told a reporter, "I have more experience than all of them put together, and you can throw Dick Swett in there, too."

Bass spent about $ 180,000 to defeat his opponents in the primary and made campaign spending a major issue in the election. While in the state legislature, Bass had written a law limiting campaign spending and agreed to abide by it himself. By signing a state form, he promised not to spend more than $250,000 each on his primary and general election campaigns. Though Swett aides said at the time that he would also be guided by this limit, Swett never signed the form required by Bass's law and went on to spend some $800,000 for his campaign. Swett aides said the incumbent Congressman declined to commit to the limit in case it became necessary to counter independent expenditures from groups like the National Rifle Association, which favored Bass. The NRA was outraged that Swett had switched positions and voted for the automatic weapons ban.

Ultimately, Bass broke his pledge in the general election by spending some $268,000, and he paid a $6,400 fine. But this came in December, long after he had irrevocably vanquished Swett, 51 to 46 percent. (Bass's overall spending still amounted to just $448,000.)

Throughout the campaign, Bass frequently blasted the significant amounts of money Swett got from outside of New Hampshire. Ironically, this gave Bass the opportunity to hammer Swett for the kind of advantage that helped Bass himself family connections. Swett's connection was his out of state father in law, influential California Representative Tom Lantos, a senior Democrat. In Swett's successful maiden 1990 campaign, Lantos not only gave Swett money from his own campaign but also helped his son in law raise money elsewhere. The Boston Globe reported that 90 percent of Swett's money came from out of state. His 68 individual big contributors in one 1994 filing period included 30 from California, nine from Oregon, and only six from New Hampshire addresses. Bass hit those facts hard."Dick Swett thinks this is a game," he said right after the primary. "He and his California and New York powerful special interests think this race will be easy.... Well, Dick Swett has a surprise coming."

Swett also tried to play the family card. "You have to understand the office of Congressman isn't an entitlement," he said at a Democratic rally. "It isn't brought to you by lineage or birth. You certainly cannot buy it." Swett, a Yale grad, claimed that Bass was a "spoiled rich kid" and a "silk-stockinged Republican."

Bass's family card worked. And, this time, Swett's failed.

While voters did not fall for the spoiled rich kid line, Basswho loaned his campaign some $90,000 of his own moneycouldn't exactly be called impoverished. He flies his own airplane, a four-seater Maule M-5. During the mid 1980s he commuted in it between his hometown of Peterborough, New Hampshire, and the architectural-panel business he and his brothers own in suburban Washington, a flight of two and a half hours. He recalls with a chuckle that, as an undergraduate, he managed to persuade the Dartmouth Athletic Department that flying lessons were an athletic exercise. He learned to fly out of the tiny Post Mills, Vermont, airport. When he came to the College he listed among his hobbies "antique auto restoration." These days he likes to restore reproducer pianos, a kind of player piano that automates the intensity of sound as well as the notes. "I also have a collection of antique gas engines," he notes.

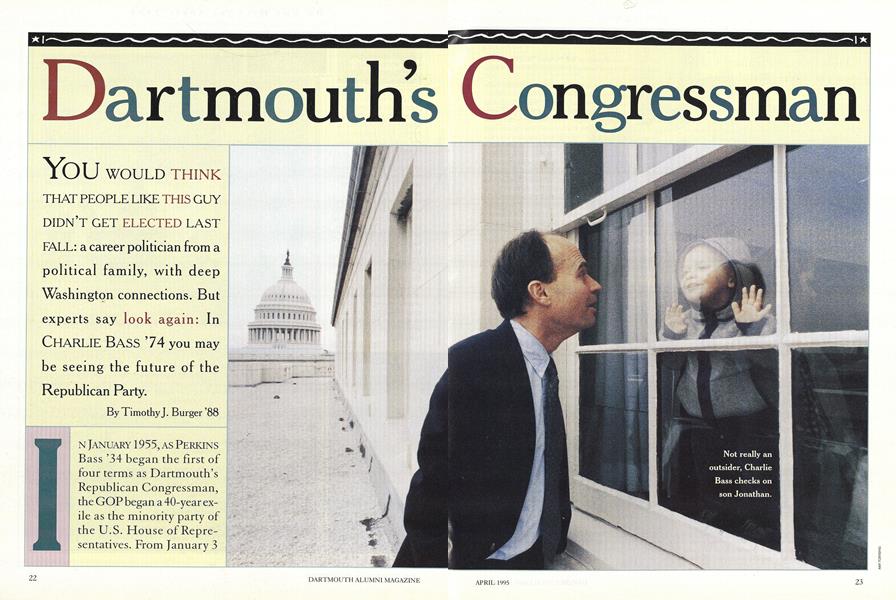

He has little time for these hobbies today. Like other freshmen Representatives who are pointedly avoiding setting roots in Washington many are sharing apartments or even sleeping in their offices Bass plans to get back to New Hampshire virtually every weekend. While in D.C. he is living in one of the two apartment buildings he bought with his brothers during the mid-1970s. He occupies a one-bedroom apartment on 17th and R Strees,a short subway ride from Capitol Hill. His wife, Lisa, and two young children, Lucy and Jonathan, come for an occasional visit. One of his chief issues is finance reform; he wants to free states to impose more of their own restrictions, like those he helped impose on New Hampshire. Bass also supports term limits, and he is one of the few unreserved supporters of Presidential hopeful Lamar Alexander's "cut their pay and send them home" proposal to convert Congress into a part-time legislature. And he is a deficit hawk, eager to cut federal spending dramatically. His business experience should help. As a partner with his brothers in High Standard Inc., a manufacturer of exterior coverings for shopping malls and other buildings, he helped downscale the company during the recession of the early 19905. Gross sales went up to some $6 million in the mid-eighties and are about $3 million today. Bass says he has seen situations in which "the owners would just contort themselves to save key employees. And then the owners would go bust and the employees would have new and better jobs in three days and the owners would be up to their ears in debt." He adds that "it's hard to fire people," but he makes it clear he can do it. In Congress, he says, "I think what we're in the process of doing now is making equally difficult decisions."

These days, you can work on slashing the budget and still be considered a moderate. But Bass doesn't like the label. "I think the going word now is a fiscal conservative and a social moderate. How does that sound ? " It sounds good, says Warren Rudman, the former U.S. Senator from New Hampshire who co-authored the Gramm Rudman deficit-reduction act. Rudman says Bass is "quite conservative on traditional Republican issues of defense and foreign policy, fiscal policy. And he'll tend to be more moderate on social issues involving individual liberty and individual right of action."

This is exactly the direction in which the entire Republican Party should head, according to Democrat Paul Tsongas '62, who is Rudman's partner in the Concord Coalition, a group that works for deficit reduction. "I think the movement that the Republican Party has to go through is toward the mainstream on social issues if it wants to be the majority party," says Tsongas.

If Rudman and Tsongas are right, the party's future lies with Charlie Bass and his kind. kind

Not really an outsider, Charlie Bass checks on son Jonathan.

TIMOTHY J. BURGER is a reporter for Roll Call, a newspaper covering Capitol Hill. He is a former Whitney Campbell Undergraduate Intern for this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

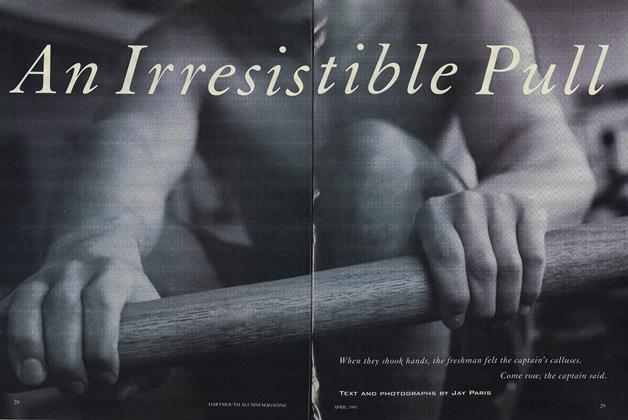

FeatureAn Irresistible Pull

April 1995 By Jay Paris -

Feature

FeatureFathoming the Practical Universe Dan and Whit's

April 1995 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe World's a Game

April 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

April 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1992

April 1995 By Jessie W. Levine -

Class Notes

Class Notes1991

April 1995 By Sue Shankman

Timothy J. Burger '88

-

Article

ArticleMilk and Cookies

OCTOBER • 1987 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIf I Could Do It Over

December 1987 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Article

ArticleA Sun-Powered Race Between Two Very Different Schools

December 1988 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Article

ArticleThe Jungle's Front Man

APRIL 1990 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Article

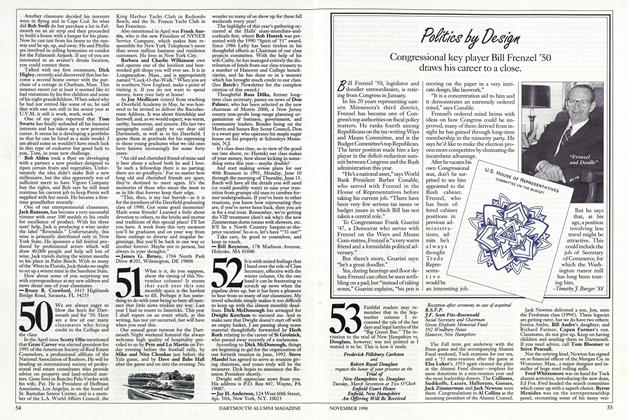

ArticlePolitics by Design

NOVEMBER 1990 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Feature

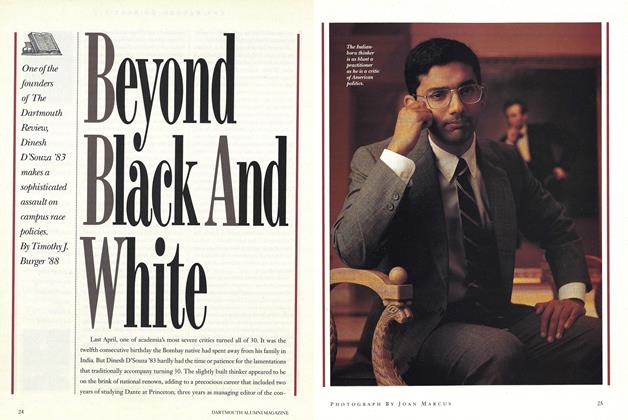

FeatureBeyond Black And White

JUNE 1991 By Timothy J. Burger '88

Features

-

Feature

FeatureArtists

March 1977 -

Feature

Feature"The Greatest Problem in American Biology

November 1983 -

Feature

FeatureWe Were Soldiers

Mar/Apr 2003 By CASEY NOGA '00 -

Feature

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Cover Story

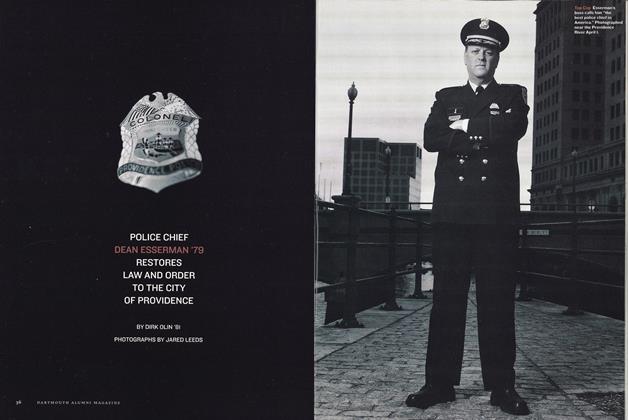

Cover StoryPolice Chief Dean Esserman ’79 Restores Law and Order to the City of Providence

July/August 2005 By DIRK OLIN ’81