HOW COURTS GOVERN AMERICA by Richard Neely '64 Yale University Press, 1981. 233 pp. $15

A graduate of Dartmouth and the Yale Law School and now chief justice of the West Virginia Supreme Court, Richard Neely has written an incisive, wide-ranging study of American governmental institutions. In his analysis of legislatures, courts, administrative agencies, and especially in his examination of the complementary political functions among them, Neely is remarkably discerning and compelling. "Remarkably" primarily because the book purposely and easily assumes a down-home tone, free of convoluted clutter. It is fun to read.

Neely is an inquisitive observer, and few topics relating to policy-making escape his attention. Not surprisingly, therefore, this book has many theses. Among the major ones is, first, that the court system in the United States is a political institution. It is so not because the men and women who serve as judges are politically ambitious (though this they may be; see, e.g., Neely himself), but rather because, particularly in the recent era of public law litigation, courts make policy.

Second, Neely believes that because of their unique structural features the courts are the least likely among governmental institutions to be manipulated for selfish purposes from within. Neely is an unabashed enthusiast of a strong and independent judiciary, which he views as both a check on and a catalyst for other governmental institutions.

Third, courts are especially competent in "general interest" lawmaking, while legislatures excel in "special interest" governance — a distinction, however, that Neely readily admits is not clear-cut. But he sees both forms of lawmaking as legitimate and is well aware of the dilemma, inherent in a pluralistic democracy, between carrying out the will of the majority and meanwhile protecting the interests of multiple and overlapping minorities.

Fourth, Neely concludes that it is possible to specify with some objectivity those areas in which judicial lawmaking is needed and thus appropriate. At this point, Neely's analysis comes close to the stuff of political science, though he would disclaim any such intention. As a prime example of appropriate judicial lawmaking Neely points to the reforms in criminal procedural law made during the 1960s and 19705. He readily concedes indeed, he heralds the proposition that the writers of the First and Sixth Amendments had no inkling that their words would be subject to the particular expansive interpretations of the past two decades. But Neely delights in revealing the important lawmaking function of constitutional interpretation and in seeking to dispel doubts about the legitimacy of such authority. Reform of pre-trial criminal procedures, he argues, was a legitimate area for judicial policymaking because the courts could successfully remove the disparity between the "myth" of evenhanded procedures and the actual operation of the system before the 1960s.

At the other end of the spectrum Neely analyzes the school finance cases, where courts are asked to alter the formulas for funding of public schools to compensate for the low revenue-producing capacities of property-poor school districts. In such cases, Neely believes, judicial intervention could put the courts in the improper position of being mere appropriators of money and hence explicit advocates of one specialinterest group (in this case, the education lobby). There is no consensus, moreover, that the judicially managed result is superior to the alternatives arrived at by other political institutions.

Clearly, not everyone will find Neely's arguments persuasive, but his focused and consistent attempt to define what he obviously believes to be a legitimate and a principled realm of judicial activism makes this an important book, especially to non-lawyers. As Neely says in introducing the principle of constitutional interpretation (overstating the case but nonetheless getting the point across): "The truth of the matter is that judges do not say these things with a straight face; they are talking in a code which most of the bar understands."

An assistant U.S. Attorney in New York.Kate Pressman held clerkships with both theU.S. Court of Appeals in Washington and theU.S. Supreme Court after finishing HarvardLaw and the Kennedy School.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat keeps them going? A 'Mystic Glue' Perhaps

May 1982 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Feature

FeatureTerrorism and the Niceties of Justice

May 1982 By Joseph W. Bishop Jr. -

Feature

FeatureImpacts simply positive

May 1982 -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

May 1982 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

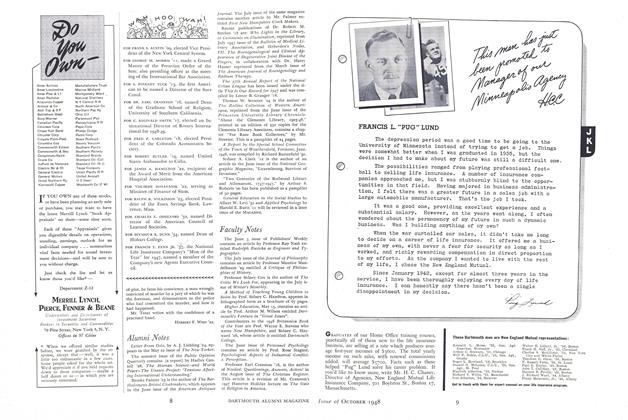

Class Notes1964

May 1982 By Alexander D. Varkas Jr. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

May 1982 By John L. Gillespie

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Notes

October 1948 -

Books

BooksWine of Fury

November, 1924 By Eric P. Kelly -

Books

BooksSIDEWHEELER SAGA

July 1953 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksAmerican Democracy and Asiatic Citizenship

April 1919 By L. D. WHITE -

Books

BooksTHE UNITED NATIONS AND ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CO-OPERATION.

October 1951 By M.O. CLEMENT -

Books

BooksImages

APRIL • 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77