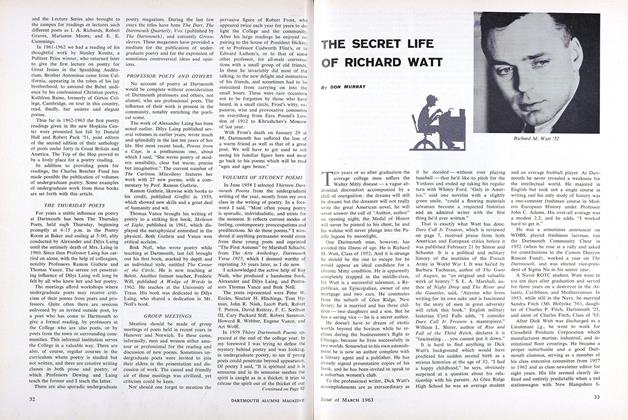

By RichardM. Watt '52. New York: Simon andSchuster, 1963. 344 pp. $5.95.

Here is the story, told in full for the first time, of the best kept secret of World War I: the mutiny of the French Army in 1917, its suppression, and the regeneration of the Army as a fighting force. Richard M. Watt '52 says that the writing of this book was "a labor of love"; his labor has produced a gripping narrative no reader will want to put down before finishing it. It rests on a foundation of scholarship both thorough and unobtrusive.

The mutiny, this "convulsion of exhausted troops," expressed disillusionment and despair that had been building up ever since the war began. The French soldier had been trained to attack with the bayonet: in 1914 the bayonet charges were mowed down by machine guns; during the first five months the French lost 754,000 men. Both sides were forced into trench warfare, whose methods and horrors are graphically explained and described by Mr. Watt. The new "butcher generals" spent lives lavishly in futile attacks; afterwards, they sometimes used firing squads to "shoot for example" troops who failed to accomplish, or would not try to accomplish, missions that were impossible to accomplish.

During 1915 the French Army lost 1,549,000 men; during the first ten months of 1916 it lost 861,000 men. Under Petain's capable command it stopped the Germans at Verdun; the new Commander-in-Chief who emerged from Verdun was not Petain, however, but Nivelle, and the failure of the fatal offensive associated with his name was the immediate cause of the mutiny. "The Army had been promised victory, and, as always, the promises had been lies. Now the troops learned that they had been sent into a battle the success of which had been doubted by almost every one of their leaders." The "Nivelle Offensive" began April 15, 1917. On April 29 the French Army began to mutiny and in a few weeks there were just two reliable French divisions between the Germans and Paris; it was admitted later that "collective indiscipline" had infected elements of fifty-four divisions.

The mutinies continued from May until September, when a last uprising in a Russian brigade was quelled by loyal Russians and French .75s. Petain, Nivelle's successor, halted the mutinies and by improving the hitherto wretched lot of the French soldier gradually restored discipline. Mr. Watt believes that the number of those executed, while greater than the official figure of 23, was much smaller than rumor reported. The mutinies were accompanied and followed by a campaign of pacifism, defeatism, and treasonous dealing with the Germans carried on by the political left. As Petain quelled the mutinies, Clemenceau, becoming Premier, crushed the leftists.

Mr. Watt sums up at the end of his scholarly and fascinating account: "The Army and the people faltered - but only for a moment. . . . None dare call it treason."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

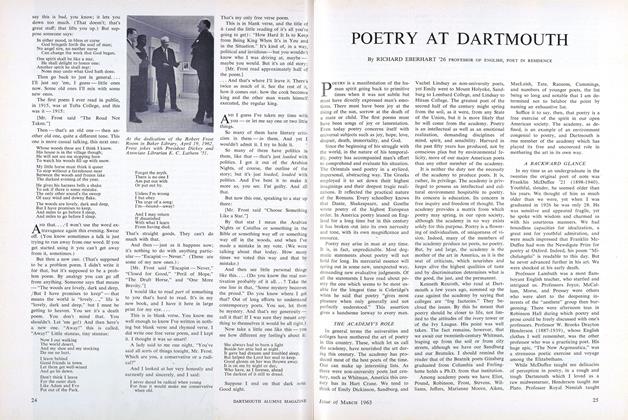

FeaturePOETRY AT DARTMOUTH

March 1963 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Feature

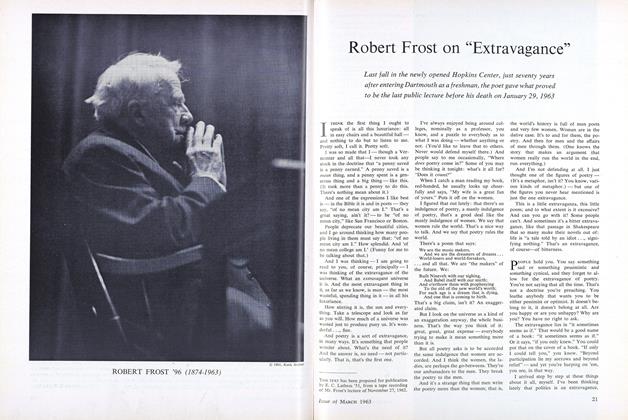

FeatureRobert Frost on "Extravagance"

March 1963 -

Feature

FeatureTHE SECRET LIFE OF RICHARD WATT

March 1963 By DON MURRAY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1963 By JOHN HURD, HUGH M. MCKAY -

Article

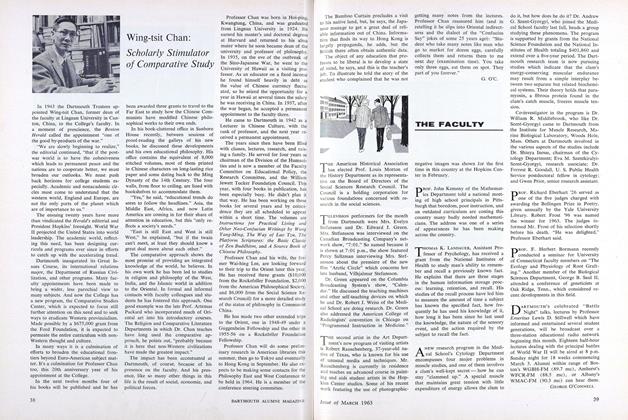

ArticleScholarly Stimulator of Comparative Study

March 1963 By G.O'C. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1963 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, ALBERT W. FREY

JOHN C. ADAMS

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE CONSTITUTION AND THE MEN WHO MADE IT

January 1937 -

Books

BooksEDITOR’S PICKS

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Books

BooksAND TO THINK THAT I SAW IT ON MULBERRY STREET,

December 1937 By Dr. Seuss, Alexander Laing '25. -

Books

BooksBYSTANDER

MAY 1930 By E. P. K. -

Books

BooksLunar Light

JAN./FEB. 1978 By JOHN B. LYONS -

Books

BooksANTICIPATING YOUR MARRIAGE.

November 1955 By RALPH P. HOLBEN