As the Easter weekend began, the first session of a three-day symposium on the liberal arts at Dartmouth was brewing a tempest in 105 Dartmouth Hall. There a decorous throng in suits, ties, skirts, and pumps filled most of the seats and President McLaughlin was on hand to initiate things.

The symposium was designed by Hans Penner, dean of the faculty. "It started last summer," he explained, "when the Montgomery Endowment committee was discussing bringing in speakers on education to initiate the McLaughlin era of Dartmouth's history. I was asked what I thought, and being the iconoclast I am, I said why not support a liberal-arts symposium fully run by our own faculty? We have a wonderfully competent faculty and a 200-year tradition of liberal arts. Why go outside? Great, the committee said, you run it."

So he did, convening the College's present and past Third Century Professors into what he called a "good blue-ribbon group" to hammer out topics and call for abstracts. The Dartmouth faculty was invited to submit papers to a symposium competition carrying four prizes of $1,000 each and six smaller ones. Twenty-three papers were submitted blind to the blueribbon committee, which chose four to be presented in full and six others to be condensed for 15-minute panel presentations.

Raymond Hall of the Sociology Department dropped the event's major topics squarely on the table in the first session, citing sexism, racism, elitism, classism, and ethnocentrism as the problems which compromise liberal learning at Dartmouth and also beset American society as a whole. He called for "a critical release of liberally trained students devoted to the study of human relations," saying it "could contribute enormously to the reduction and perhaps elimination of tensions based on human differences — at home and in the world."

The following day, English teacher Jeffrey Hart '51 pooh-poohed atomic war, sexism, elitism, and acne and called for a revival of Plato, Homer, Dante & Co. in the interests of eliciting intelligent conversation among undergraduates. Richard Joseph '65 of the Government Department brought his international experience to bear in a cri de coeur for extension of the liberal arts to cultures other than our own: "As long as we do not bring development studies to the center of our concerns in the liberal arts, to that extent we are declaring that we are not ready to step down from the pinnacle of our cosmic arrogance and join hands in a common enterprise with the many others who travel through space and time with us on this odd but perfectible planet." When a student made an irritated appeal to Joseph for specific curricular recommendations, moderator Peter Bien of the English Department stepped hastily into the breach of liberal decorum. "We are in a transitional period, we who are teaching the liberal arts," he told the student. "We are not sure what to teach or why we teach it — though you're not supposed to know that."

Gregory Prince, associate dean of the faculty, spoke in praise of the "healthy tension" at Dartmouth between research and teaching, and government professor Laurence Radway asserted that a liberal arts education produces liberal values and declared, "An intellectual elitism deserves an honored place in higher education." In one of the more popular presentations, Jay Parini of the English Department made a ringing appeal to colleges and universities to reject the corporate model, in which, he said, not rocking the boat is paramount. He urged them to return to "the Athenian ideal, that place where 'there is no sovereignty but that of the mind, and no nobility but that of genius.'

Mary Jean Green of the French and Italian Department and Brenda Silver of the English Department jointly delivered a paper pointing out that the liberal arts tradition is inherently male, a study of men by men. They challenged the notion of objectivity and the definition of power currently prevalent in the academy, asserting that women's studies, which call for the replacement of competition by affiliation and for the disruption of hierarchy and authoritarianism in the classroom, could revitalize the liberal arts. There was a cry of "Brava!" from the audience.

Bruce Pipes of the Physics Department gave vent to his bitterness over "disappearing" at cocktail parties when it becomes known he is a physicist. He asserted thar scientists are liberal, too, and complained of having to teach "pidgin physics." Pipes urged that Dartmouth offer a course on the history of science, saying, "No student should be graduated from Dartmouth without a real understanding of how science has contributed to ― not caused ― both the bright and the dark sides of modern society."

Soft-spoken Alvin Converse, associate dean of Thayer School of Engineering, praised the entry of black studies, Native American studies, and women's studies into Dartmouth's curriculum, and called for increased distributive requirements in hopes of fostering student creativity. "Scientists seldom provide us with the opportunity to invent," he lamented, and he recalled with pleasure the matriculation requirement once suggested by former Hopkins Center director Peter Smith: In the interests of wisdom, creativity, and skill, every student should be required to make a chair and use it.

The final speaker, Professor Charles Wood, a medieval specialist who left investment banking for the hallowed halls of history, asked, "Does a knowledge of the Dark Ages prepare students for Wall Street?" His answer was a resounding yes, and he concluded by stressing his faith in the survival of liberal education.

"I am quite satisfied," said Penner when it was all over. "I see this as a preface. Once we find our center, we can begin to think in terms of recommendations to the faculty, but right now that's premature."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat keeps them going? A 'Mystic Glue' Perhaps

May 1982 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Feature

FeatureTerrorism and the Niceties of Justice

May 1982 By Joseph W. Bishop Jr. -

Feature

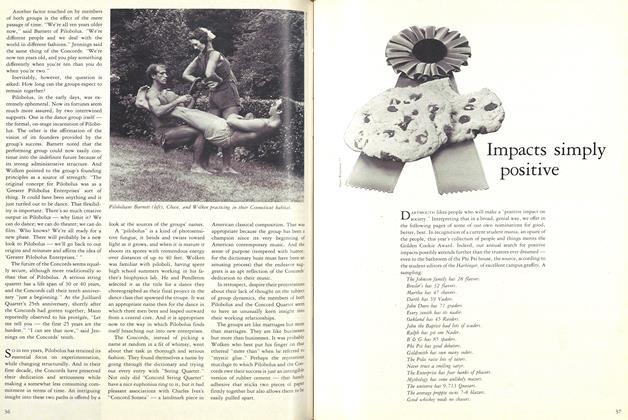

FeatureImpacts simply positive

May 1982 -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

May 1982 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

Class Notes1964

May 1982 By Alexander D. Varkas Jr. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

May 1982 By John L. Gillespie

Article

-

Article

ArticlePALAEOPITUS DECIDED

June, 1914 -

Article

ArticleBASEBALL

March 1919 -

Article

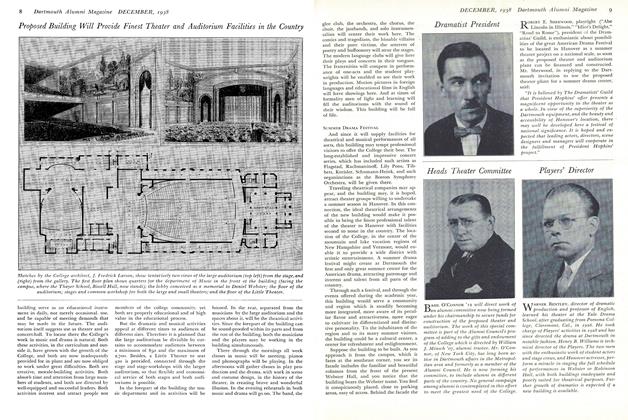

ArticleProposed Building Will Provide Finest Theater and Auditorium Facilities in the Country

December 1938 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

FEBRUARY 1966 By BILL BARNET T'65 -

Article

ArticleThe Winners

FEBRUARY • 1988 By Townley Slack '88 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Today is His Tribute

May 1948 By WILLIAM H. HAM