PRIVATE WOMAN, PUBLIC STAGE: LITERARY DOMESTICITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICA

OCTOBER 1984 HENRY TERRIEPRIVATE WOMAN, PUBLIC STAGE: LITERARY DOMESTICITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICA HENRY TERRIE OCTOBER 1984

by Professor Mary Kelley Oxford University Press, 1984. 409 pp., $24.95.

In this valuable book, Prof. Kelley explores the careers of twelve women writers who flourished in 19th century America and, in the process, uncovers a largely-ignored dimension of our literary and social history. The lives of these writers were, as Kelley abundantly shows, full of contradictions. In a time when men were assumed to be the "proper" economic providers for the family, these women put bread on the table through their literary earnings. Their very origins as writers were embedded in contradictory circumstances. Born into families of superior social status, they yet found themselves members of an inferior gender. Educated to match their social station, they were expected to devote themselves to domestic duties.

Unlike such militants as Margaret Fuller and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, however, these women tended to accept the conventional view of women's role at the same time they were so busily subverting it. They were, in short, reluctant revolutionaries so filled with ambivalent feelings about their own activity that many of them adopted pseudonyms to disguise their authorship, and all of them shied away from public display or revelation.

Nevertheless, despite the personal doubts, the obstacles of domestic obligation, these courageous women wrote prolifically and succeeded in the world of commercial publishing. What convergence of forces made their opportunity? In general terms, the humane spirit of the Enlightenment and the political ideals of the American Revolution had prepared the way for changing attitudes concerning women. Then as women, frequently driven by domestic necessity, began to seek new outlets for their energy and imagination, they as well as male writers benefited from numerous developments in the young republic. Economic and population growth, new technology in printing, the beginnings of an effective copyright law, increased royalties, the appearance of subscription libraries these and other factors vastly increased the potential readership and facilitated access to it. The net result was nothing less than a radical alteration of the literary marketplace which provided a chance for women to make money at something other than school teaching.

A casual look at Prof. Kelley's table of contents might lead one to assume a simple structure for the book: 12 writers, 12 chapters. In fact, her procedure is far more complex and sophisticated, though just as symmetrical. The 12 chapters are divided into three parts in groups of four, and each part has a primary topic. Under "Peculiar Circumstances, " Prof. Kelley outlines the social, cultural, and economic milieu in which her 12 writers lived and worked. "The Notice of the World" treats the difficulties of simultaneously managing a domestic life and a literary career. "Warfare Within" focuses on the personal dilemma of women who wrote critically of the double standard, of the pressure on women to conform, of male treachery and female martyrdom and yet somehow seemed to find their happy endings in marriage. Within the three parts of the book, each chapter has its own primary topic, or rather "leitmotif" (education, economics, self-revelation, cultural roles, moral aims, etc.); for the divisions are never exclusive and the topics appear and reappear in different combinations throughout. This form has the advantage of leading the reader to a cumulative understanding. At the same time it demands considerable powers of concentration and memory. It is not always easy to keep the cast of characters straight, nor is it easy to distinguish among innumerable novels whose plots have a remarkable sameness. Still the repetition brings home to us the essential point that these many stories, both real and fictional, are finally one story - the story of woman's lot in a male-dominated society.

In examining this story, the literary historian will be moved to ask some questions. Why, for example, did so much writing produce so little significant literature? Surely British women confronted the same obstacles and inhibitions as their American cousins. Yet, where was the American Jane Austen, Emily Bronte, or George Eliot? Of the writers under consideration, only Harriet Beecher Stowe emerges as a major figure, and in her case it is difficult to weigh social against literary power. Or again, why were the great novels about feminist issues in nineteenth-century America all written by men? One thinks of The Scarlet Letter, The Portrait of a Lady,The Bostonians, Sister Carrie. Yet these questions are perhaps premature since Prof. Kelley disavows the role of literary critic and invites further study of her subjects. What she has done here, with impressive scholarship, is to document the work of women who themselves "found their place in history by documenting so-called lives of non-being, by making the invisible visible."

Professor Terrie is the senior member of theCollege's English department. His most recent publication an edition of selected stories of Henry fames will be reviewed in aforthcoming issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

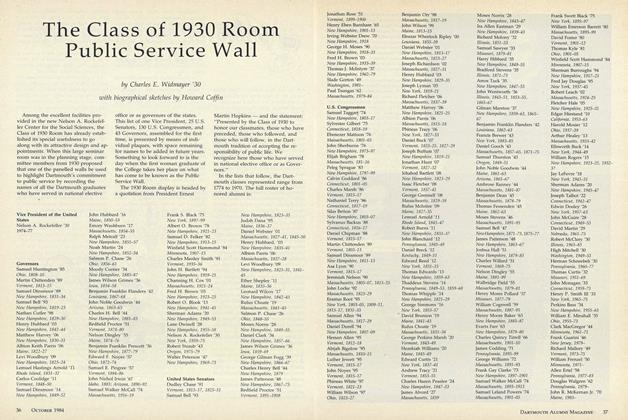

FeatureThe Class of 1930 Room Public Service Wall

October 1984 By Charles E. Widmayer '30 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGeared for Success

October 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

Feature"Little Joe" Wentworth, 1900: Scholar, Athlete, Gentleman

October 1984 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

Feature"The Computer Revolution" Revisited

October 1984 By George O'Connell -

Article

ArticleA Post-game Peregrination

October 1984 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

ArticleGetting Better with Age

October 1984 By Gayle Gilman '85

Books

-

Books

BooksPrinciples of Taxation

January 1915 By C. A. PHILLIPS -

Books

Books"THE PRESTIGE VALUE OF PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT,"

FEBRUARY 1930 By Charles Leonard Stone -

Books

BooksWINTER IN VERMONT

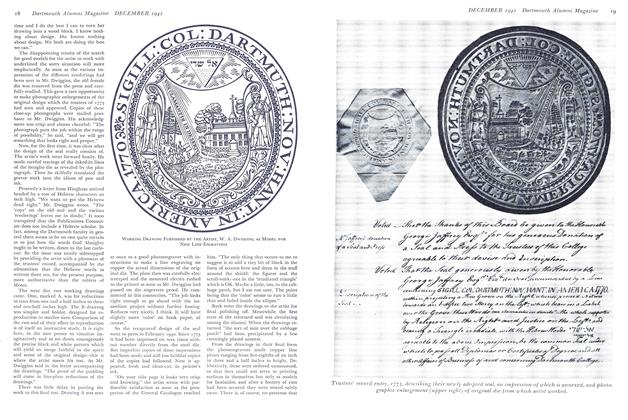

December 1941 By Harold G. Rugg '06 -

Books

BooksLIFE ALONG THE CONNECTICUT RIVER.

June 1939 By Harold G. Rugg '06. -

Books

BooksMARKETING IN AN UNDERDEVELOPED ECONOMY: THE NORTH INDIAN SUGAR INDUSTRY.

JULY 1963 By KENNETH R. DAVIS -

Books

BooksDENMARK ON FIFTY DOLLARS

May 1937 By Raymond W. Jones