Some 20-odd years ago in my Dartmouth incarnation I wrote a piece entitled "The Computer Revolution" for the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. Inspired by those two computer geniuses, John Kemeny and Tom Kurtz, I rhapsodized about a future free of intellectual drudgery. Computers would do the scut work while great and notso-great minds would be freed to think great thoughts or try experiments that would be too detailed or time-consuming to be practical otherwise. Or computer-users could just relax, smell the roses, and await a print-out's wisdom.

That scenario has worked out for a good many people, I suppose. As for me personally the jury is still out. Computer technology is undoubtedly a boon to mankind, but I suspect that it is making me obsolescent at best, obsolete at worst.

All this came to mind recently when I read an article in The New York TimesMagazine by its education editor, Ted Fiske. He featured Dartmouth's pioneering efforts with computers and the article was very flattering. Obviously, Dartmouth had taken the lead in computer education and other institutions were just trying to catch up.

It led off with a quote from a Dartmouth '84, Nicholas Armington, who said that while in college he had "never written a paper on a piece of paper." Instead he had done his writing on one of the many word-processing terminals around the campus and could research, write, and amend his prose by punching a few buttons. A clear, cleanly-typed paper resulted.

As one who has laboriously hunt-andpecked out lots of words on lots of pieces of paper, I was understandably more than just a little jealous.

The article went on to say that Mr. Armington had also used the Dartmouth computer to study philosophy, create random patterns for a course in art and technology, and to brush up on his French.

I applaud him and the gadgets that made these things possible, but I'm forced to conclude that they are not for me. I like to think that I'm not dumb, just inept and intimidated by any machine more complicated than a screwdriver.

You see, I belong to another generation, one that considered slide rules, dial telephones, portable typewriters, etc., the final word in beneficial technological advances.

I blame my obsolesence primarily on my blunt, splayed fingers. I am a lousy typist and if psychologists had such a scale, my "digital dexterity quotient" would be near zero. If I am patient enough and have a good supply of typist's "white out," I can manage on my comfortable, rebuilt Royal upright. But confronted with an electric model, I tend to panic. When I hit or nearly hit a desired key, my finger tends to hit two, whereupon the machine does a war dance and skitters across the page with lots of "sssssss's and aaaaaa's" and "zzzzzzzzz's." The machine seems to be saying to me, "Who in heck is in charge up there? Shape up or ship out, fella!"

I usually get so discombobulated that I forget any ideas that I wanted to put on paper.

In my brief and reluctant encounters with computers, the same phenomenon occurred. My history of inept inputs made me nervously aware that I might inadvertently enter some highly secret program, one that sets off World War III or transfers $8 billion from Chase Manhattan Bank to the account of a Vermont sugarbush farmer. The odds against something like this happening are astronomical, of course, but I watch science-fiction movies and I've learned from the newspapers that some family on welfare has just won $5 million in a lottery prize against improbable odds.

Despite my digital ineptitude, I have managed to cope with some electronic devices. When pocket calculators were introduced, my blunt fingers were a handicap until a friend showed me a way to use the eraser end of a pencil to stab at the tiny buttons. This often helped me in balancing my checkbook and calculating my income taxes and if I really have to learn the square root of 76,543, it might come in handy. But that hasn't happened yet.

The calculator was an improvement oyer the slide rule of my collegiate days and a quantum leap from the paper-and-pencil long division that Sister Lioba taught me in grade school and even the logarithm exercises that I endured in high school.

I've used the eraser-end technique to cope with the new touch-tone telephones too. When I became a Dartmouth administrator in 1957, the Hanover phone system was a "Number please" operation. You talked to a friendly Lily Tomlin type. If you didn't remember the number, you just asked for Eddie or Charlie or whomever. Usually the call went through expeditiously. The introduction of dial telephones undoubtedly saved the local phone company a lot in wages and benefits, but it complicated my life. It put the onus on me. I either had to remember the callee's number or look it up. Because I'm also a numbers nebbish who can recall his own phone or social security number only on good days, this so-called advance proved time-consuming. For me, that is, not the phone company. Their productivity increased; mine declined. We can see the same phenomena in computerized supermarkets, self-service gas stations, banks, etc. You, the consumer, are required to provide the services that previously went with the operation.

Productivity or counterproductivity? I wondered.

I unleashed these thoughts over lunch on my friend Lester, a near contemporary, expecting sympathy and support. Instead I got a devastating analysis of my problems.

"You could become a neo-Luddite, of course," he said.

A neo-Luddite?

"Dummy! You must have slept through those history courses." He explained that the Luddites were a dissident group in 19th century England who opposed the Industrial Revolution. They rioted and smashed the machines that they thought caused technological unemployment.

"You could do that with computers, but I wouldn't advise it. The laws are pretty strict.

"Or you could go to school and learn computering."

These were not the solutions I wanted, so, like a hypochondriac, I sought a second and even a third opinion.

Ernie Roberts, a colleague at Dartmouth as sports information director and later a sports editor of The BostonGlobe, said, "You've got to be kidding. The VDT (Video Display Terminal) is the greatest development since sour mash bourbon." In the office, a press box or even at home he composes and edits copy without hazarding the whims of transcribers or copy editors. But I noticed that he has slim, tapering fingers. He could have been a piano player. A third opinion from a near-contemporary: Recently I collaborated on a book project with George Gallup, Jr., president of the widely known polling organization. He said, "We'd be helpless without computers." There is so much raw data that attempting to process it without high-speed computers would be nearly impossible, he explained. I had asked him because George, a friendly giant of a man, also has blunt, splayed fingers.

But why, I inquired, didn't he have at least a computer terminal in his office instead of the 1940s vintage Royal manual that stood beside his desk?

He explained that he had virtually unlimited access to all the computer data he ever needed, but when it came to analyzing and writing, "my old Royal and I are a team. She understands me and my thought processes and I write better with her."

So my quandary remains. Expecting sympathy and support from contemporaries, I got instead a rude awakening. Obsolesent, obsolete, or current seemed to be my options.

I suppose I could, or should, try my eraser-tip technique. But first I want to find a computer that doesn't intimidate me, one like George Gallup's Royal that understands me.

George O'Connell, author of "The Dartmouth Disease" (DAM, Oct. '83), was Director of News Services at Dartmouth in thelate 50s. John Tonseth is a professional illustrator who lives in Norwich.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

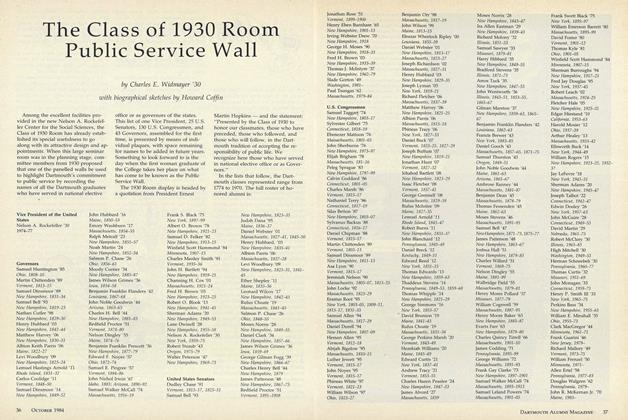

FeatureThe Class of 1930 Room Public Service Wall

October 1984 By Charles E. Widmayer '30 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGeared for Success

October 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

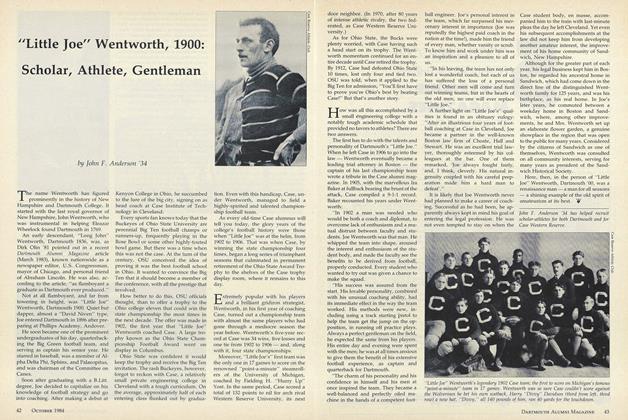

Feature"Little Joe" Wentworth, 1900: Scholar, Athlete, Gentleman

October 1984 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Article

ArticleA Post-game Peregrination

October 1984 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

ArticleGetting Better with Age

October 1984 By Gayle Gilman '85 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

October 1984 By Michael H. Carothers

George O'Connell

-

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

DECEMBER 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleTuck School Author

FEBRUARY 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

APRIL 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

OCTOBER 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

DECEMBER 1966 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Disease

SEPTEMBER 1983 By George O'Connell

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTHE RACE TO BE HUMAN

NOVEMBER 1966 -

Cover Story

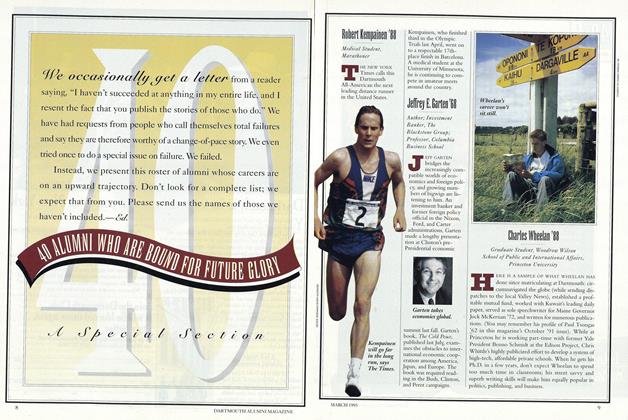

Cover StoryRobert Kempainen '88

March 1993 -

Feature

FeaturePsychology at Dartmouth

February 1958 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGILLIAN APPS '06

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BAKE A TASTY & AWARD-WINNING CUPCAKE

Jan/Feb 2009 By NORRINDA BROWN '99 -

Feature

FeatureTHE UNSUNG HERO OF THE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CASE

FEBRUARY 1969 By Susan Liddicoat