PRESIDENT DICKEY, Trustees, members of the Faculty, our honored guests, and members of the senior class, it is my duty today, on behalf of the graduating class, to bid farewell to the College.

We are gathered here after completing four years of study and at the beginning of a new life - a life entirely different from the one we have lived on campus in this happy academic isolation. It is fitting to reflect on the values our Dartmouth education has had for us and to consider the kind of world that is confronting us at the outset of our new life. This is no time for congratulation and self-gratification, but a time for decision and determination as to what we are going to do and what we are going to be.

Our four-year college life has had a different meaning for each one of us. But we have had one objective in common. It was the desire to grow, to learn, and to be bettered that brought us together on the Hanover plain, and set for us a common goal. As President Dickey once put it, our job at the College was to learn. As we look back, we have this question to answer: "How well have we done our job?" or "How far have we realized our aims and what have we learned in college?"

From psychology we have learned, for instance, that our behavior is largely the product of our irrational unconscious desires and fears; from philosophy, that any attempt to systematize our beliefs and values results in hopeless paradoxes. Mathematics has revealed that even our reason may be frustrated by contradictions. Science has taught us that man is nothing but the accidental collocation of atoms, and it has confronted us with a universe which has no provision for man's future. Bertrand Russell once wrote, "All the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all tire noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and the whole temple of man's achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins." What we have learned has more than confirmed the foregoing remark as increasingly true. The tremendous progress of science and technology has left us without a corresponding moral and spiritual conviction to cope with the new situations.

We have also witnessed, in the past four years, a ruthless suppression of a people's aspiration for freedom and independence in the Hungarian revolution, a resurgence of the 19th century imperialism in the attempted Anglo-French invasion of Egypt, and an intensification of racial antagonism as in the Little Rock incident. We also have seen the United States, the symbol of democratic liberty and prosperity, humiliated by Communist Russia in political initiative, in science, and in technology. In short, we have spent our formative years in these ever-accelerating trends towards dehumanization and demoralization.

We have been often accused of being a generation too security-minded, without ambitions, without purpose, and without creative drives, which were the marks of greatness our ancestors had bequeathed to us. We have likewise been condemned for surrendering our mental integrity and self-reliance for a suburban respectability - a "belongingness" - in an age of tranquilizers, subliminal advertisements, and psychiatrists.

Amid these facts which were disturbing, to say the least, there remained a glimmer of hope. We have learned to discover some positive values in human existence among all the forces moving unimpeded towards the degradation - even the extinction of mankind. In spite of such a pessimistic outlook, we have not become pessimists. The awareness of the hopeless problems - of the world has not dulled our courage, nor has it thwarted our aspirations; it has only convinced us that in the future there remain greater challenges to be met, and greater rewards to win.

What then are the positive values we have acquired at Dartmouth? A determination not to be deceived by cheap and crude reasonings and arguments. We have learned to demand truth, however brutal and disturbing it may be, and reject any attempt to manipulate human minds with empty slogans and maxims. We have learned the virtue of tolerance; democracy now seems to us more than a self- righteous maxim. We have also learned the wisdom of compromise, but not to compromise when it means surrender of basic values and loss of our moral integrity. In short, we have learned that human existence is a good thing, and elimination of human suffering is also a good thing. To these simple and eternal truths we dedicate ourselves anew. Although we must anticipate all manner of obstacles and hindrances and perhaps defeats, we mean to proceed with courage and perseverance wherever we are, because we have confidence in the abilities and skills acquired here, hope in our future, and firm faith in what we know to be true.

We are' now about to enter into what has been often described as a "cold world." We no longer are mere spectators. From this moment we shall be deeply involved in the affairs of the world, and our generation will be held responsible for the future of our world. Dartmouth has given us the material for such a service by molding us into effective citizens of the nation we are to serve.

Finally, as a foreign student, may I express my deep appreciation for the education Dartmouth has given me. It has been the most valuable experience of my life and, I believe, of that of all the foreign students in this graduating class. We shall carry home many a pleasant memory of our teachers and friends whose acquaintance we have been fortunate enough to make.

We shall go our ways, but we shall never forget the loyalty we all owe to Dartmouth. Many thanks and farewell.

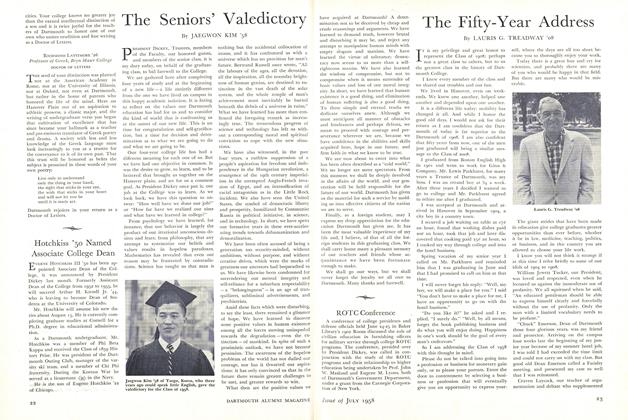

Jaegwon Kim '58 of Taegu, Korea, who three years ago could speak little English, gave the valedictory for the Class of 1958.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Examined Life

July 1958 By THE REV. THEODORE M. HESBURGH -

Feature

FeatureThe 1958 Commencement

July 1958 By C.E.W. -

Feature

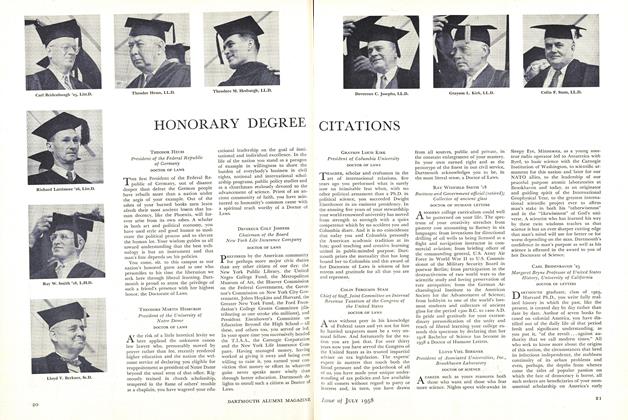

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1958 -

Feature

FeatureSix Alumni Awards Bestowed

July 1958 -

Feature

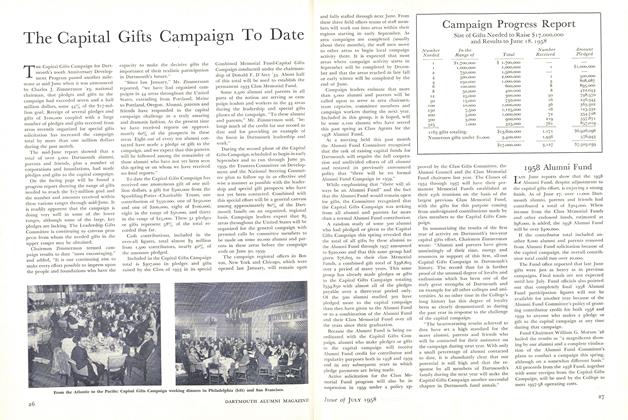

FeatureThe Capital Gifts Campaign To Date

July 1958 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1958 By LAURIS G. TREADWAY '08

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRegional Leaders Named for Campaign

February 1958 -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1961 -

Feature

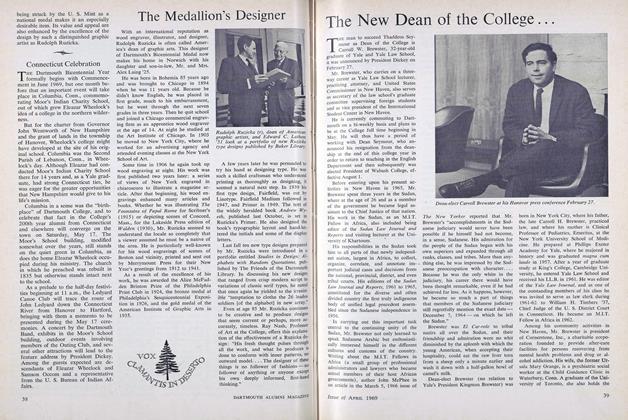

FeatureThe New Dean of the College...

APRIL 1969 -

Feature

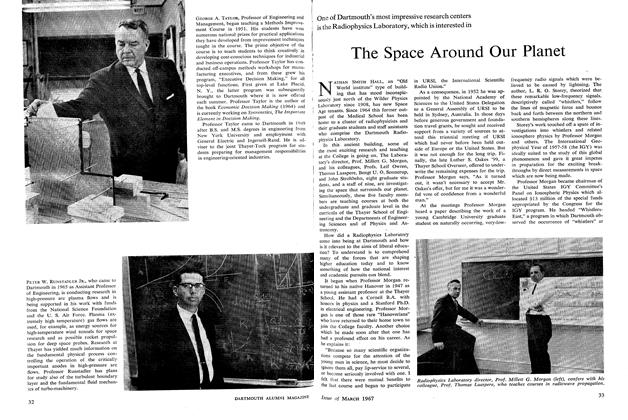

FeatureThe Space Around Our Planet

MARCH 1967 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureProfessor Jesup's Herbarium

March 1960 By JAMES P. POOLE -

Feature

FeatureBeyond the Glory

Jan/Feb 2010 By SARAH TUETING ’98