Dartmouth's Legacy in Silver

When the new Hood Museum of Art is dedicated on September 27 of this year, an engraved silver bowl with a scalloped crown will hold a place of honor in a special exhibition of "Dartmouth Treasures" in the museum's Harrington Gallery. The bowl, a "monteith," was the first art object presented to the College. In 1773 Royal Governor of New Hampshire John Wentworth, grantor of the College's original charter, gave the vessel to Dartmouth's founder and first president Eleazar Wheelock in commemoration of the school's first commencement ceremony in 1771. Over the years the bowl has come to be cherished at Dartmouth as a symbol of the institution's highest office and as a reminder of the school's humble beginnings. As such it has inspired spirited College songs and solemn rituals, as well as several reproductions of the bowl itself. Beyond its historical and symbolic associations, the handsome engraved monteith is also one of the most admired examples of eighteenth-century American silversmithing. It is the undisputed masterpiece of its maker, Daniel Henchman (1730-75), and is one of only three known Colonial American monteiths in silver.

A monteith, a large bowl with a notched rim, was used in the eighteenth century to chill wine glasses or rinse them between courses. The Dartmouth monteith has a removable crown that enables the vessel to serve as a conventional punch bowl as well.

By the time the Dartmouth monteith was commissioned in the early 17705, these bowls were still uncommon in the Colonies and had long since lost favor abroad. By choosing such an outdated though prestigious form, Wentworth was clearly more concerned with tradition than with current fashion.

In crafting the monteith, Boston silversmith Daniel Henchman worked in a conservative style characteristic of New England taste. The plain, hemispherical bowl, modest in size (just under eleven inches in diameter), is supported by a molded, splayed foot and fitted with a gracefully scalloped rim. The C-scrolls and simple drop pendants that form this cast border are the bowl's only concession to the rococo style then in fashion.

The overall simplicity of Henchman's design is echoed by the royal governor's straightforward dedication engraved on one side:

His Excellency John Wentworth, Esqr, Governor of the Province of New Hampshire And those Friends who accompanied him To Dartmouth College the first Commencement 1771. In Testimony of their Gratitude and good Wishes Present this to the Revd. Eleazar Wheelock, D.D. President And to his Successors in that Office

Below the elegant lettering, an engraved calligraphic dove holds in its mouth an olive branch, the familiar emblem of peace.

We know from the initials "N.H. scp." incorporated into the flourishes beneath the inscription on the bowl that Boston's prominent engraver and silversmith, Nathaniel Hurd (1729-77), contributed the bowl's engraved decoration. Such collaboration between silversmiths became increasingly common in the eighteenth century as craftsmen gained recognition for particular abilities. The collaboration in this instance is all the more understandable, since (Henchman and Hurd probably shared training with the same master silversmith, Nathaniel's father Jacob, and in 1753 Henchman married Nathaniel's sister, Elizabeth.

The monteith's inscription specifies that the bowl was the gift of Wentworth "And those Friends who accompanied him" to the College's first commencement. Recent research by the Hood Museum's former registrar, Margaret Moody Stier, has confirmed that the bowl was paid for by subscription, and that during the vessel's production, subscribers debated over the content and wording of the inscription. According to a letter in the New Hampshire Historical Society dated August 13, 1772, from Samuel Moody of Dummer Academy to Ammi Ruhamah Cutter of Portsmouth, some of the subscribers had hoped to include a romantic verse on the opposite side of the monteith by Boston lawyer and patriot Josiah Quincy.

It is clear from date of the letter that the monteith could not possibly have been presented at the first commencement, which took place on August 28 of the previous year. It was probably still unfinished for the second, which took place on August 26, 1772. Historian Frederick Chase would seem to be correct, therefore, when he asserted in his History of Dartmouth College that "the bowl was not actually finished and presented until March, 1773." So far no additional reference has been found to confirm the bowl's official date of presentation.

Descriptions of Dartmouth's first commencement ceremony (in which four students graduated - all of them transfers from Yale) suggest that a silver monteith might have appeared out of place amidst the College's crude facilities and rugged surroundings. By that point Eleazar Wheelock's noble plans to establish a Christian school for Indians had been realized only insofar as a few small log buildings were erected for classroom and living space. According to one account of the Commencement cited by Chase, after the proceedings "an ox provided by the generosity of the Governor was roasted on the Green, and served to the assembled multitude with a barrel of rum and the usual accompaniments." Some of the guests scorned the plain setting and what they thought to be a humble reception. Still, Wheelock took pride in the occasion and in the impressive showing of more than sixty of the governor's friends. These men had ridden with Wentworth on horseback from Portsmouth to Hanover for the ceremony. Wheelock noted in his memoirs: "a more agreeable Number of Gentlemen I never saw together upon any occasion whatsoever."

It appears unlikely that the bowl was ever used to chill glasses over the years at Dartmouth, but it probably held punch at early College functions. In a June, 1867 article in The Dartmouth, Professor Edwin Sanborn referred to the bowl as a relic of "heroic times, wisely kept for show." Its symbolic role evolved soon after. Beginning in 1909, the year Ernest Fox Nichols succeeded William Jewett Tucker as president, the monteith was incorporated into the inaugural ceremonies for College presidents. During these occasions the twopart bowl is passed gingerly from outgoing to incoming president in what is termed "the Wheelock succession." On the first enactment of this ritual (described by Ernest Martin Hopkins in TheInauguration of Ernest Fox Nichols as President of Dartmouth College), Tucker referred to the vessel "as a kind of loving cup" representing "the good will of the long succession." Upon receiving the monteith, newly inaugurated President Nichols promised to:

guard and cherish this symbol of theWheelock succession for the mightyhands through which it has passed,hands which have held high the sacredtorch of knowledge to light the homes,the work shops, the streets of theworld, that none should grope in darkness, nor lose his way, nor run intoany danger because of mental or moralignorance.

The legacy of the Wentworth bowl continued to grow. In 1929 the Board of Trustees commissioned Tiffany & Co. to make a replica in gold, which the College presented to Edward Tuck, founder of Tuck School, in appreciation for his service to Dartmouth. Five years later the International Silver Company issued reproductions of the monteith along with other historic pieces to sell to the general public. In 1958 the College presented another replica of the treasured bowl, again manufactured by Tiffany & Company, to President Ernest Martin Hopkins upon his eightieth birthday.

Today the bowl still graces College inaugurations, but otherwise it is stored with the institution's other "crown jewels." These include the official seal that was cut by Nathaniel Hurd about 1773, and a medal that was a gift of John Flude of London to Eleazar Wheelock in 1785 and which is worn by the president on occasions of state. Yet none of these treasures rivals the monteith for its rare form and fine New England craftsmanship. In commissioning such a showpiece, Governor Wentworth and his colleagues proved not only their discriminating taste and judgment, but their resolute faith in Wheelock's bold educational experiment in the northern frontier.

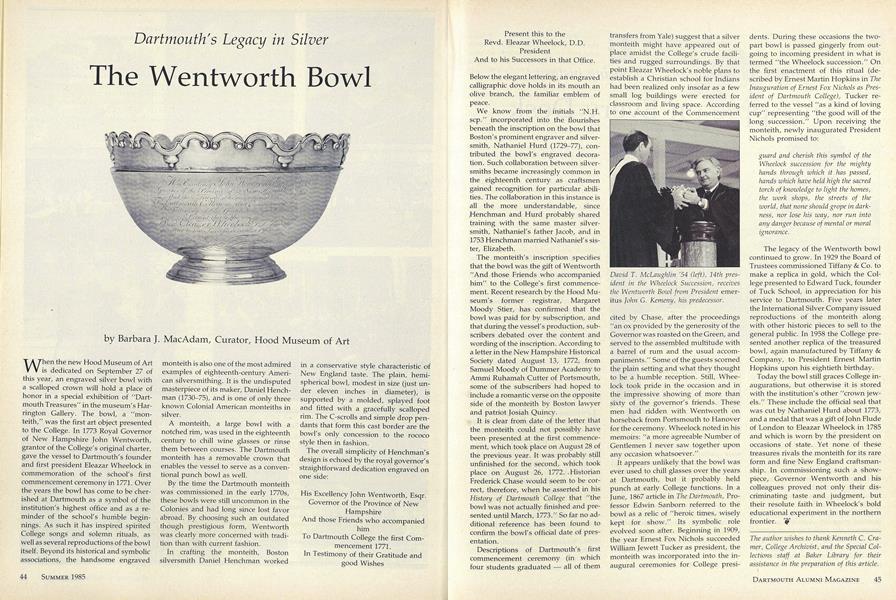

David T. McLaughlin '54 (left), 14th president in the Whedock Succession, receivesthe Wentworth Bowl from President emeritus John G. Kemeny, his predecessor.

The author wishes to thank Kenneth C. Cramer, College Archivist, and the Special Collections staff at Baker Library for theirassistance in the preparation of this article.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Humanist Ponders the Future of Liberal Education

June 1985 By Charles T. Wood -

Feature

FeatureAn Apple on Every Desk

June 1985 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Train Robbery

June 1985 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryValedictory Address

June 1985 -

Feature

FeatureReunions 1985

June 1985 By Robert Frost -

Cover Story

Cover StoryExcerpts from Beverly Sills' Commencement Address

June 1985

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Nominates Three for College Trustees

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT

JUNE • 1986 -

Feature

Feature5. Residential Life

December 1987 -

Feature

FeatureA Collection of 'Erotic Capital'

October 1980 By Margaret E. Spicer -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Long-Deferred Promise

June 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Beat of Terror

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By STUART A. REID ’08