Can a former third-string tackle lick cancer?

Your disability is your opportunity. —Kurt Hahn, founder of Outward Bound

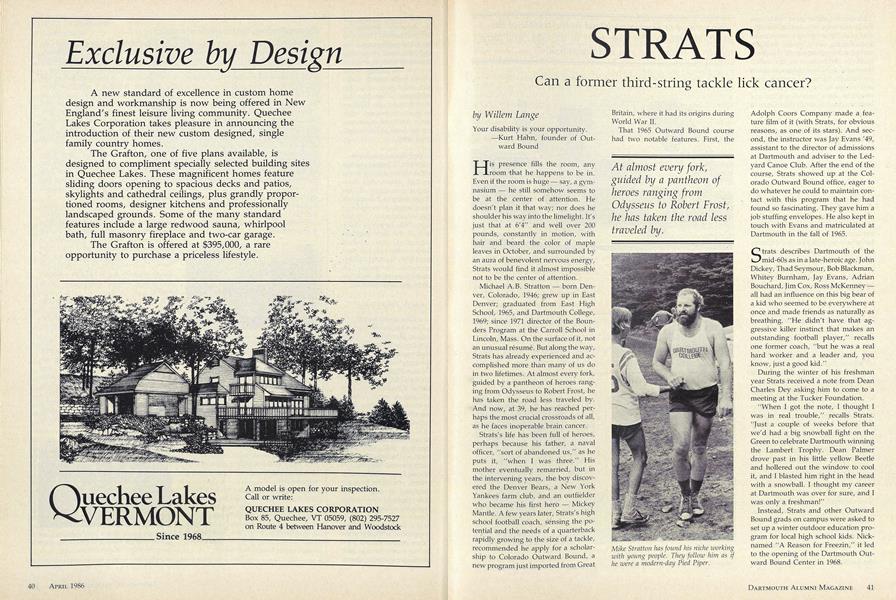

His presence fills the room, any room that he happens to be in. Even if the room is huge say, a gymnasium he still somehow seems to be at the center of attention. He doesn't plan it that way; nor does he shoulder his way into the limelight. It's just that at 6'4" and well over 200 pounds, constantly in motion, with hair and beard the color of maple leaves in October, and surrounded by an aura of benevolent nervous energy, Strats would find it almost impossible not to be the center of attention.

Michael A.B. Stratton born Denver, Colorado, 1946; grew up in East Denver; graduated from East High School, 1965, and Dartmouth College, 1969; since 1971 director of the Bounders Program at the Carroll School in Lincoln, Mass. On the surface of it, not an unusual resume. But along the way, Strats has already experienced and accomplished more than many of us do in two lifetimes. At almost every fork, guided by a pantheon of heroes ranging from Odysseus to Robert Frost, he has taken the road less traveled by. And now, at 39, he has reached perhaps the most crucial crossroads of all, as he faces inoperable brain cancer.

Strats's life has been full of heroes, perhaps because his father, a naval officer, "sort of abandoned us," as he puts it, "when I was three." His mother eventually remarried, but in the intervening years, the boy discovered the Denver Bears, a New York Yankees farm club, and an outfielder who became his first hero Mickey Mantle. A few years later, Strats's high school football coach, sensing the potential and the needs of a quarterback rapidly growing to the size of a tackle, recommended he apply for a scholarship to Colorado Outward Bound, a new program just imported from Great Britain, where it had its origins during World War II.

That 1965 Outward Bound course had two notable features. First, the Adolph Coors Company made a feature film of it (with Strats, for obvious reasons, as one of its stars). And second, the instructor was Jay Evans '49, assistant to the director of admissions at Dartmouth and adviser to the Ledyard Canoe Club. After the end of the course, Strats showed up at the Colorado Outward Bound office, eager to do whatever he could to maintain contact with this program that he had found so fascinating. They gave him a job stuffing envelopes. He also kept in touch with Evans and matriculated at Dartmouth in the fall of 1965.

Strats describes Dartmouth of the mid-60s as in a late-heroic age. John Dickey, Thad Seymour, Bob Blackman, Whitey Burnham, Jay Evans, Adrian Bouchard, Jim Cox, Ross McKenney all had an influence on this big bear of a kid who seemed to be everywhere at once and made friends as naturally as breathing. "He didn't have that aggressive killer instinct that makes an outstanding football player," recalls one former coach, "but he was a real hard worker and a leader and, you know, just a good kid."

During the winter of his freshman year Strats received a note from Dean Charles Dey asking him to come to a meeting at the Tucker Foundation.

"When I got the note, I thought I was in real trouble," recalls Strats. "Just a couple of weeks before that we'd had a big snowball fight on the Green to celebrate Dartmouth winning the Lambert Trophy. Dean Palmer drove past in his little yellow Beetle and hollered out the window to cool it, and I blasted him right in the head with a snowball. I thought my career at Dartmouth was over for sure, and I was only a freshman!"

Instead, Strats and other Outward Bound grads on campus were asked to set up a winter outdoor education program for local high school kids. Nicknamed "A Reason for Freezin," it led to the opening of the Dartmouth Outward Bound Center in 1968.

During his senior year Strats took the first decisive step on that less-traveled road. "Was I going to continue as a third-string tackle, or get more involved in this outdoor stuff?" He deep ened his involvement in the out-ofdoors and right away began to doubt his wisdom. There was a winter climb with a high bivouac on Mount Lafayette, there was a week of camping and bushwhacking in the College Grant in April, and finally there was a cruise in 30-foot open whaleboats along the coast from Boston to Hurricane Island, Maine.

"It was incredible!" he recalls. "After several days and nights at sea -and it was cold in April we arrived at Hurricane Island in the middle of the night, stumbled up to some tents in the dark, and were told to be ready for a run and dip at 5:30 [a.m.]. We ran around the island in sea boots at 5:30 and jumped off the pier into the water that was almost ice. Before breakfast we helped rescue some people who were overcome in their camp by fumes from a gas stove. We spent the day putting boats in the water, sorting gear, carrying groceries, talking to delinquent kids who were also up there to help out.

"Everywhere I looked, there were interesting people doing exciting things - fixing boats, setting up a ropes course, building cabins, writing books, designing programs. I thought to myself, 'Boy! this is for me!' "

And so it was. Since that spring, Strats has done very little else. Immediately after graduation, he went to work for the Dartmouth and Hurricane Island Outward Bound schools. In his spare time, he visited other Outward Bound programs from Scotland to Zambia. He completed an apprenticeship at a wooden boat-building school and began building dories. He spent a year on a Norwegian squarerigged school ship and saw that young boys barely in their teens could learn to go high aloft with the best of sailors and stand watches in all kinds of weather. He worked in dozens of programs adapted for delinquents, substance-abusers, and the handicapped.

When young people meet Strats, they can't resist him. Here is someone they can depend on, literally and figuratively. As often as not, he has one or two kids hanging from his neck and arms as he tries to talk. This is the way the headmaster of the Carroll School found him at Hurricane Island in 1971 when he was looking for someone to start a confidence-building outdoor program for his dyslexic students. Invited to visit the school, Strats drove past Walden Pond (the former home of another of his heroes) just before he got there. He wasn't sure just what dyslexia was, but he took the job, and, with breaks for occasional adventures, has been there ever since.

Dyslexia is caused, researchers think, by an improper level of testosterone during one stage of fetal development, resulting in the inhibition of left-brain growth. Thus dyslexics' verbal and linguistic ability may be severely impaired, while, to their intense frustration, their creative skills are compensatingly greater. They see the images the rest of us do, but often as kaleidoscopic bits, constantly shifting and without framework or reference points. Children (and adults) with the condition may have great difficulty concentrating or remembering. An undiagnosed dyslexic typically falls behind peers in school work, develops defensive behavior to explain failure, and loses confidence a self-perpetuating cycle.

At the Carroll School, students range in age from 7 to 19. Strats blew onto the campus like a huge, redhaired Pied Piper and began to assemble his program, which he called Bounders. None of the kids were required to get involved with it, but few could long resist the climbing ropes, kayaks, and paddles lying around the office/ shack where Strats lived at the foot of a hill below the school. Before long the students were exploring the countryside around Walden Pond on bikes, snowshoes, and skis. They combed deserted seashores. They slept overnight in a hut they built themselves, in a jail, in a boat, even in a bomb shelter and up in a tree. They visited loggers, blacksmiths, fishermen all people Strats had befriended in his endless wanderings.

Strats has what is probably the world's largest private collection of inspirational aphorisms, and his Bounders have heard most of them at one time or another. Never mind that in the eye of at least one dyslexic kid the program's motto, "BOUNDERS CAN BE WICKED HARD BUT WICKED FUN!" becomes "BOUNDERS CAN BE WIKED HEARD TUB WIKED FUN!" It still means the same thing.

Strats is as unabashedly proud of his devotion to aphorisms as he is of the congregation of heroes who guide and enrich his life. The kid who was himself inspired by idealists remembers, as he approaches 40, what it was like to be little and feel alone. He has sometimes been called the Mr. Rogers of Outward Bound. The Carroll kids respond warmly to him, and their paeans for the program are unending. "What was the hardest part of the Bounders program?" one child was asked. "Sleeping in a tree!" was the response. "If you could do the course again, what would you do differently?" came a second query. "Sleep in the tree longer!"

Another of Strats's students was more contemplative. "As I sit on the side of the bank, my mind wanders back to a time 34 months ago when I was not the least bit interested in rock climbing or soloing in being on my own ... until a great big man came along and showed me a different way. If I had not met such a man, I wonder where I would be now."

Parents are equally enthusiastic in describing the changes in their children. "I have never seen a program that has accomplished so much in such a short time. Jimmy has gained an immeasurable amount of self-confidence," said one parent, And another said, "The fee that seemed such a large sum to find (on top of school tuition), with each passing Bounders session became one of the best investments we ever made."

Strats's work at Carroll has not gone unnoticed in the outside world either. The Boston Jacyees honored him as one of the area's ten outstanding young leaders in 1982. In 1984, Esquire magazine recognized him as one of "the best of the new generation men and women under forty who are changing America." (His name appeared on the list between those of Streep and Stockman.)

The Bounders program is well established, and Strats is now, too. Some years ago he moved out of his shack on the school grounds, and he and his wife, Nancy, now live with their three children in a residential area nearby. ("What color house?" he asks. "White with green trim, of course!")

Then, during the summer of 1985, after experiencing severe headaches for a few months, Strats had two seizures. Although he was in the middle of a new program he wanted to finish -mixing dyslexic, Down's syndrome, and "regular" kids together in a summer course he checked into the hospital for tests. On August 5 he learned that he had an inoperable brain tumor.

Some six months later, on a late winter rainy day, Strats is home with the kids. Nancy is away at a healing workshop for the families of cancer pa tients; tomorrow Strats will join her. He moves more slowly than he used to, and stiffly, but he is still in perpetual motion. He feeds the wood stove, hands us some magazine articles he has saved for us, leads us downstairs to look at slides. He is still at the center of the room.

"Come on," he says. "You've got to see this'restaurant, the Willow Spring. It's the all-time favorite of truckers and Outward Bounders." Once there, he eats lightly his sense of taste has been burned by the radiation, and the pH of his saliva lowered and hooks his thumbs ruefully under his belt. "Two-twelve. You've never seen me this light before!"

He is adamant in calling himself not a cancer victim, but a cancer patient "emphasis on the 'patient.' My last CAT scan showed that the tumor had been arrested, which seemed to make the doctor pretty happy, so I guess it's looking good." Watching the cold rain stream down the restaurant window, he frets that for the time being he cannot drive, that he is missing the new students in the Bounders program this year. But he has not collected the inspirations of others for so many years for nothing.

Hundreds of his former students and friends have sent him cards and letters. It's hardly surprising that their sentiments sound familiar to him. He saves them avidly, along with the other hundreds of photographs and slogans that adorn the walls and ceilings of his shack and his office.

They are reminders that the beloved teacher's legacy is perhaps the richest of all.

One of Strats's favorites among all his aphorisms, from Henry David Thoreau's Walden, says it best: "I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived."

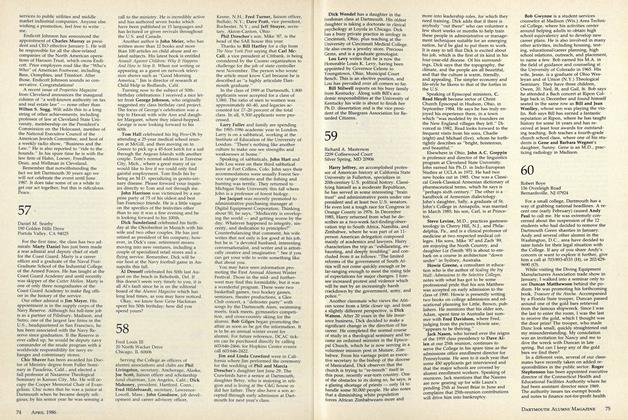

Mike Stratton has found his niche workingwith young people. They follow him as ifhe were a modern-day Pied Piper.

Bounder-of-the year Max Cobb (right) sailing a dory in Boston Harbor six years ago withhis friend David Arrow. Cobb, now a junior at the College, has just been elected presidentof the DOC, an achievement which Stratton called "the biggest boost in my career."

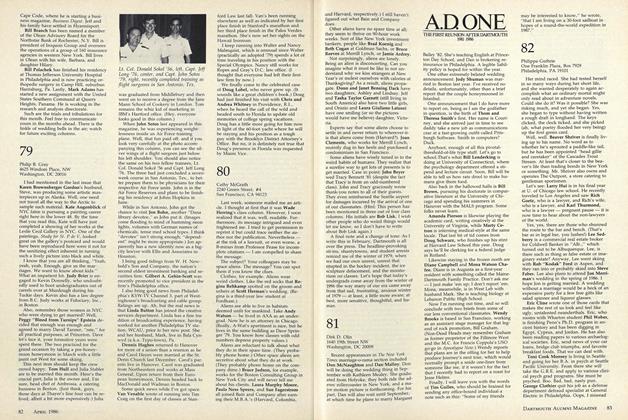

The effects of radiation therapy have deprived "Struts" of his hair but not of his positiveoutlook on life. With him and his wife, Nancy, are their three children - left to right,Lance, 17 months; Kelsey, four years; and Courtney, six years old.

At almost every fork,guided by a pantheon ofheroes ranging fromOdysseus to Robert Frost,he has taken the road lesstraveled by.

"V\fe arrived at Hurricane Island in the middle of thenight, stumbled up to some tents in the dark, and weretold to be ready for a run and dip at 5:30."

In 1984, Esquire magazine recognized him as one of"the best of the new generation men and womenunder forty who are changing America." (His nameappeared between those of Streep and Stockman.)

Willem Lange, an accomplished outdoors-man himself, is also a carpenter and a free-lance writer in the Upper Valley. He chron-icled the history of the Dartmouth OutingClub for the January/February 1984 Alumni Magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Peace Corps at 25

April 1986 By Laura T. Hammel -

Feature

FeatureRecent Accessions in European and Graphic Art at The Hood

April 1986 By Hilliard T. Goldfarb -

Article

Article"Kiki" McCanna: Steward of Sanborn

April 1986 By Lee McDavid -

Article

ArticleRave Reviews?

April 1986 By Dorothy L. Foley '86 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1986 By Richard A. Masterson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

April 1986 By Philip B. Gray

Willem Lange

-

Article

ArticleThe Greening of Labrador

MAY 1983 By Willem Lange -

Feature

FeatureThe Outing Club at 75

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Willem Lange -

Article

ArticleDoc Weider '60 and the Illogical Alaskan Adventure

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 By Willem Lange -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

NOVEMBER 1986 By Willem Lange -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEHe Hears the Call of the Wild

Sept/Oct 2000 By Willem Lange

Features

-

Feature

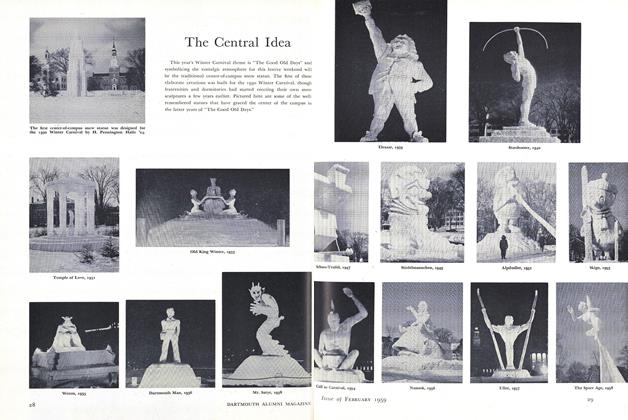

FeatureThe Central Idea

FEBRUARY 1959 -

Feature

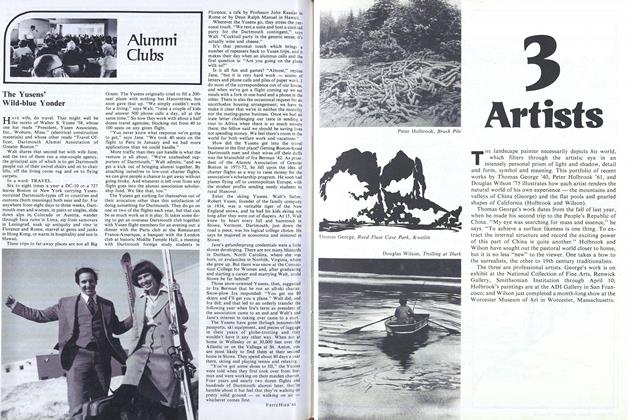

FeatureArtists

March 1977 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryKevin Ritter '98 Lloyd Lee '98, Brad Jefferson '98

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

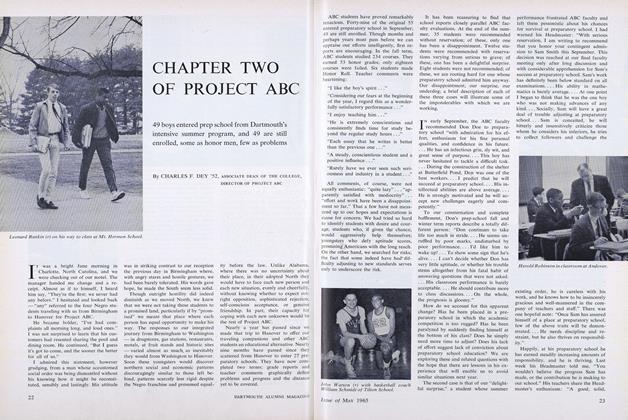

FeatureCHAPTER TWO OF PROJECT ABC

MAY 1965 By CHARLES F. DEY '52 -

Feature

FeatureThe Gentleman's B-Plus

February 1992 By Eric Konigsberg '91 -

Feature

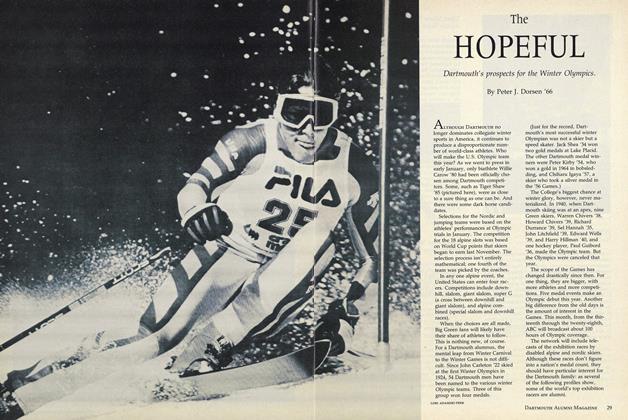

FeatureTHE HOPEFUL

FEBRUARY • 1988 By Peter J. Dorsen '66