Inauguration of the 14th President: The Spirit of Eleazar Wheelock ... Transmitted through his Successors'

SEPTEMBER 1981Inauguration of the 14th President: The Spirit of Eleazar Wheelock ... Transmitted through his Successors' SEPTEMBER 1981

"THE Wheelock Succession," a phrase X that now and then seems a little shopworn from overly casual use, took on renewed significance as David T. McLaughlin '54 became the 14th member of that august brotherhood on June 28. The personal dimension was almost palpable as Richard D. Hill '4l, trustee chairman, installed the new president officially with the conveyance of the College charter, issued in 1769 by George III of England, and as John G. Kemeny welcomed McLaughlin to the succession with the symbolic transfer of two historic artifacts, the Wentworth Bowl and the Flude Medal.

The evocation of the spirit of Eleazar Wheelock was just short of mystical. As both Ernest Martin Hopkins '01 and John Sloan Dickey '29 had harkened back under like circumstances to the eloquence of William Jewett Tucker, 1861 "I believe that the greatest possession of the College has been and still is the spirit of Eleazar Wheelock in so far as it has been transmitted through his successors. ..." so the 13th president used the words of the ninth to describe the enduring influence of the first.

"The charter of Dartmouth," Tucker had said in welcoming Ernest Fox Nichols to the succession, "unlike that of any college of its time so far as I know, was written in personal terms. It recognizes throughout the agency of one man in the events leading up to and including the founding of the College. And in acknowledgement of this unique fact it conferred upon this man founder and first president some rather unusual powers, among which was the power to appoint his immediate successor. Of course this power ceased with its first use, but the idea of a succession in honor of the founder, suggested by the charter, was perpetuated; so that it has come about that the presidents of Dartmouth are known at least to themselves as also the successors of Wheelock. ... I do not know in just what ways the impulse of this man's life entered into the life of my predecessors. To me it has been a constant challenge."

"Like President Tucker," Kemeny added, "I too have drawn strength periodically from the history of Wheelock and his successors." Protesting that the succession is "a matter of the spirit, not of material possession," he then gave over to McLaughlin's keeping the scalloped silver bowl, presented in 1771 by Governor John Wentworth to Eleazar Wheelock "and to his successors in office," and then the Flude Medal, originally given to John Wheelock and inscribed to "the president of Dartmouth College for the time being." (See also page 21.)

"Dear friend," said Kemeny to McLaughlin, "my time has expired; yours is just beginning."

For all its solemnity, the inaugural weekend was a curiously light-hearted celebration. There were happy tears, a lot of mildly self-depreciatory jokes, and at special moments busses all round. It was the term is inescapable the Dartmouth family rejoicing.

The festivities started with an intime little dinner in Alumni Hall for 265 of Dartmouth's and the McLaughlins' nearest and dearest friends, a remarkably informal affair put on by the trustees. Few long dresses, no black ties,, an unprecedented scarcity of green blazers. Fresh strawberries followed very, very good beef. No speeches, just three warm toasts, each dressed up with a pleasant surprise. Lots of bubbly and an enormous amount of bobbing up and down as nice things were said about this Dartmouth notable or that. McLaughlin urged anyone harboring a complaint to "take it up with the president tonight." The forecast was for "clear skies tomorrow," he announced with a broad grin, "and that may be the first time in some time that the weather has really cooperated with me."

The first surprise was McLaughlin's: the establishment by an anonymous donor of the Jean Kemeny Scholarship Fund for undergraduate women. His toast was to both John and Jean Kemeny "in gratitude for the marvelous leadership that he has provided to this College in very difficult times. Trustee Hill, in his turn, after cataloguing some of John Kemeny's noteworthy attributes, raised his glass to proclaim, "My God, what a man! Thank you very much, John. On behalf of the Dartmouth community, thank you for you and Jean." His announcement was the John G. Kemeny Parents Professorship in Mathematics, endowed with $1 million by three sets of non-alumni parents, who also requested anonymity.

In response Kemeny said that his gratitude was magnified because "one of my great disappointments throughout our major fund drive when we were fortunate in bringing in so many new chairs was that I had totally failed my own department."

Of all the kindness that had come the Kemenys' way as he prepared to step down, one compliment had meant the most to him personally, he related. Feeling sometimes that "perhaps I was not as much of an extrovert as is'expec'ted of a president of Dartmouth . . . , nothing has pleased me more than to have heard a number of people during the past few weeks refer to me as 'the outgoing president of Dartmouth.' "

Then he offered McLaughlin "seven simple rules that can make you a successful president." Noting this "last opportunity after tomorrow's ceremonies he doesn't have to listen to me anymore," Kemeny quoted a former head of Colgate University on what an alumnus looks for in a president:

I expect him always to be articulate andeloquent but never to be verbose and longvAnded.

1 expect him to be firm but not rigid,"responsive but not permissive, cheerful butnot vacuous, dignified but not pompous.I expect him to raise a whole lot of moneybut never to leave the campus.

I expect him to protect academic freedombut to make life pretty rough on dissenters.I expect him to get my favorite nephewsand nieces into college but never to loweradmission standards.

I expect him to have winning football teamsbut not to over-emphasize athletics.

And above all, I expect him to be bold andinnovative but not to change any of theways that things have always been done.

The "outgoing president of Dartmouth" had a surprise up his sleeve, too. With a budget of over $100 million to administer, he warned McLaughlin, "the president of the College has control of almost none of it." Hence the significance of an inaugural gift from the family of the late Harvey Hood '18, a $200,000 discretionary fund, for McLaughlin to use as he will "without having to ask the Board of Trustees or your financial vice president to try to ease your first year or two in office and to give you the degree of freedom that every new president deserves."

After Kemeny's toast to the McLaughlins and their future at Dartmouth, an apparently spontaneous, obviously unrehearsed, genuinely moving a cappella rendition of "Men of Dartmouth" started at one table and spread throughout Alumni Hall.

Inauguration Day dawned bright and clear, in splendid cooperation with David McLaughlin. It was the sort of morning that nostalgia can delude one into recalling as typical June weather in Hanover: the skies were cerulean, the breezes gentle; warm sunshine filtered through the surviving elms on Baker Lawn as it rarely seems to in actuality on ceremonial days dappling the rainbow of academic regalia. A fanfare, composed especially for the occasion by Frank Logan '52 of the development staff and played by him on the Baker chimes, preceded the processional marches performed by the Vermont Symphony Brass Quintet.

Provost Leonard Rieser '44 presided in that capacity over his second Dartmouth inaugural; Chaplain Warner Traynham '57 invoked blessings on "this festival of this institution's life," on the new president, and on "the future he and we will share";

Kemeny introduced, first among the honored guests, his predecessor" in the Wheelock Succession, John Sloan Dickey; Governor Hugh Gallen brought greetings from the state of New Hampshire; and Yale President A. Bartlett Giamatti, offering greetings on behalf of Eleazar Wheelock's alma mater, enlivened the occasion with a witty and gently irreverent perspective on Dartmouth's founder.

He read a florid characterization of Wheelock by a Yale contemporary ... a gentleman of a comely figure, of a mild and winning aspect. . . . His preaching and addresses were close and pungent, and yet winning, ... so that his audience would be melted even into tears. ..." This encomium,

Giamatti suggested, "constitutes a fit refutation to the words of Yale's president during the Revolution: 'lt was a singular event Dr. Wheelock's rising to the figure he did with such small literary furniture. He had much of the religious politician in his make.' "

Giamatti marveled at Wheelock's "dynastic creativity." The original Dartmouth faculty, he noted, had all been Yale undergraduates, were all but one Wheelock sons or sons-in-law the exception being the husband of a Wheelock niece. "Ancient proof ancient proof," the Yale president intoned to the vast amusement of the faithful assembled, "of the strength of that grand term 'the Dartmouth family.' "

"For all the genetic engineering," he went on in more serious vein, "these Yale men who came north on the Connecticut

. . . did not come to the great forest to found another Yale. They came and founded something unique and glorious in its own splendid right and that is Dartmouth."

In his inaugural address (the complete text of which follows), businessman McLaughlin sounded like a dyed-in-thewool academic so much so that TheDartmouth editorialized rather testily in its next issue over the perceived implication "that students would lose some freedom to faculty demands." Responding specifically to McLaughlin's suggestion that the Dartmouth Plan for year-round operation might need modification in the interest of greater continuity and more contemplative pace, the editors cautioned that "the education of Dartmouth students is a fragile process that should not be tinkered with lightly."

David McLaughlin's first official act was to confer an honorary doctorate of laws on his predecessor; his second was to make Jean Kemeny a Doctor of Humane Letters. In this, he followed the precedent set in 1970 by Kemeny, whose own first acts as president were the awarding of honorary degrees to John and Christina Dickey.

The recessional done, it was off to the Bema for punch and cookies and good wishes for the McLaughlins and the Drs. Kemeny. The line was long and the principals no doubt hand- and footsore as well as hungry before they reached the buffet luncheon in Alumni Hall.

Monday, June 29, 7:30 a.m. found President McLaughlin on the tennis court, according to the most impeccable sources. The following evening found him, along with 1,000 other people, at Cook Auditorium (seating capacity: 400) to hear Gloria Steinem lecture on "Feminism and Authoritarianism." In a virtuoso display of presidential power, he whisked the whole affair off to more commodious Spaulding Auditorium, leaving red tape shredded at his feet. M. B. R.

THE value of a college is a reflection of its past, is measured in the present, and is judged on its potential to influence positively the future. On that basis Dartmouth is indeed a wealthy institution. She is rich in heritage and strong in purpose. That fortunate condition exists due to the commitment and devotion of thousands of men and women both past and present, many of whom are assembled here today on this historic occasion. Dartmouth's strengths are manifest in the quality of its faculty, alumni, students, and officers and in the dedication of its trustees to this institution. But in significant measure the vitality of this academic center is the product of inspired and courageous leadership passed down through the Wheelock Succession and embodied in the presence here today of the 12th and 13th presidents of the College, John Sloan Dickey and John George Kemeny. owe to them our everlasting gratitude for their many years of selfless service to the College's cause.

Today s Dartmouth stands at a challenging crossroad in its pursuit of academic excellence. We share a moment in time with other institutions of higher learning which face hard choices as to the future course of their endeavors. In making the critical decisions that will shape the College in this millennium and into the next, Dartmouth's president and trustees must as our predecessors have done look to the letter and spirit of Dartmouth's venerable charter as fashioned by her Yale-educated founder and as defended successfully by one of her most illustrious sons before the highest court in this land.

While not explicit in the charter but evident in practice, the College was founded in the cause of service service to society through the education of young adults who have the capacity and the competence to make a difference, service to humanity through the discovery of new knowledge, and service to a higher being through the development of conscience and a standard of morality that benefits all mankind.

The fulfillment of our purpose has taken different forms at various times in the 212-year history of this institution. Our proud legacy has positioned the College as a distinguished institution dedicated to "all liberal arts and sciences" and committed to excellence in undergraduate education. This commitment is reinforced by the programs of graduate study and by three historic professional schools which contribute to and share in its high standards of quality and which are distinguished unto themselves by the influence of the liberal arts environment in which they exist. The undergraduate program would be less rich without their positive influence.

It serves us well to remember that the College has never wavered from its original purpose. Many of our sister institutions are today rediscovering the value of a disciplined undergraduate curriculum in the liberal arts, which Dartmouth in steadfast pursuit of Wheelock's vision never abandoned. Along with but few other pre-Revolutionary colleges, we are unique in our uninterrupted flow of graduates who have received the benefit of an education designed to expose them to the discipline of questioning what others accept as truth, to teach them how to analyze and assimilate a great range of knowledge, to apply that knowledge to the solution of increasingly complex problems, and to reinforce their individual sense of values in distinguishing right from wrong. It has been and will continue to be Dartmouth's role to provide an academic program which gives Dartmouth graduates the intellectual tools needed to discover themselves as young adults and to make a positive contribution to society by continuing their education and personal growth throughout their lifetimes. To be faithful to the Wheelock tradition, Dartmouth must, as John Dickey so ably said, educate its charges to be "ongoing learners."

AT no period in history has the role of the College been more critical. The impact of national and international concentration of technology and sciences over the past several decades has resulted in the availability of new tools for mankind that have pushed against the outer limits of our capacity for intelligent application. The next generation of technical advancements will have an even greater potential for changing the nature of our society in an interdependent world. Whether this technology ultimately serves society to better the human condition, or, in the alternative, becomes a negative force threatening our civilization will depend on the skills, the understanding, and the judgment of those entrusted with its use.

Those responsibilities will bridge into the next century, to be discharged in part by men and women who will graduate from this college in the next few decades. They must be men and women who are comfortable with technical subjects, who have a keen sense of history, and who have the knowledge and understanding of other societies. Above all, they must be men and women who have the cultural sensitivity and the wisdom to use knowledge for the enhancement of all mankind. They will be men and women who have the education to seek fulfillment in their lives through the courageous pursuit of truth.

Never has the case for a rigorous education in the liberal arts been stronger. Never has the historical role of the College been more important.

It is indeed ironic that at this time of need, the environment for education is beset with so many uncertainties. Higher education, particularly private higher education, has already crossed the threshold into an era of "survival of the fittest." The challenge ahead will necessitate limiting the effect of the uncontrollable adverse factors by exploiting the opportunities which exist in those sectors of our environment which we can influence.

I believe Dartmouth can not only meet the challenge, but in so doing seize the opportunity to establish even more firmly the College's standing as a premiere liberal arts institution. There is littie we can do to mitigate the pressure that will emanate in the next decade from demographic changes which will result in a sizable reduction in the number of men and women available to attend our colleges and universities. Similarly, it is beyond the reach of the College to alter significantly in the short term the adverse effects of inflation and the instability of the world's political scene. These negative external factors can only be countered through the continued maintenance of high educational standards for our students and faculty, through the exercise of prudent fiscal management, and by the sustained loyalty and generosity of the private sector, and particularly the Dartmouth alumni on behalf of their College.

Beyond these uncontrollable phenomena, however, are a number of other factors which are within our collective ability to influence. The first of these bears directly on the quality of our academic program. Any institution aspiring to ongoing academic excellence must have a faculty of first rank. In Dartmouth's case this must be a core of teacher-scholars who share a commitment to the transmission and advancement of knowledge and who possess the critical spirit which is as ready to challenge existing theories as to verify them.

WHILE my adult training has not been in academia, I am dedicated to encouraging an atmosphere in which intellectual and scholastic activity flourish, for without that healthy turmoil the College would surely lose its edge of scholarly excellence. Sustaining the quality of Dartmouth's faculty and reinforcing their dedication to the purposes of the College during a period of "steady state" will pose a major institutional challenge. Over the next decade it is anticipated that the College will experience only a 10 to 12 per cent turnover of its existing tenured faculty. It therefore becomes imperative that we not only provide meaningful advancement opportunities for our talented junior faculty members through a willingness to accept somewhat higher tenure ratios for a period of time, but that we also reassess our system of allocating tenure to assure that we are responsive to the long-term needs of society.

These efforts must be augmented by the availability of resources to provide opportunities for the development of our untenured faculty members as accomplished teachers and as respected scholars. There is no group of men and women more important to the future excellence of Dartmouth College. At the same time there is no group under more intense pressure for demonstrable performance than our junior faculty. We simply cannot allow these pressures to reduce the quality or the diversity of our next generation of senior faculty members on whose shoulders our future rests.

The diminished rate of infusion of new faculty in the foreseeable future also requires that we place a higher priority on making the College environment more conducive to ongoing faculty renewal. While it does not appear educationally desirable or economically feasible to eliminate Dartmouth's innovative program of year-round education, the institution must address forthrightly those aspects of this process that detract from our educational quality.

A continuation of the frenzied pace and the resulting discontinuities within the faculty is not acceptable over the longer term if we are to continue to achieve the levels of excellence to which we are dedicated. There is no reasonable alternative but to continue to search for those changes that will to sustaining high scholarly achievement even at the cost of some reduction in the scheduling options now available to undergraduates.

A program for providing future opportunities for faculty development should include the encouragement of academic collegiality and an environment that promotes mentor relationships among senior and junior faculty members. Great teachers instruct not only undergraduates and graduate students, they also teach and learn from their colleagues. In recognition of this, and through the great generosity of Harle and Kenneth Montgomery '25, resources have recently been made available to create a faculty center. These resources will assure funding of this program for at least three years. The existence of a faculty center which will include dining and social facilities has the potential to improve significantly the quality of the professional environment. Thanks to the Montgomerys, such a faculty center can now be a reality and if reasonably successful can become a permanent part of the Dartmouth campus.

The dedication of resources to enhance the vitality of our academic assets requires difficult decisions involving institutionwide priorities. In recent years Dartmouth, like other centers of learning, has experienced a continuing erosion in the purchasing power of those who work here. The disparity between the levels of compensation in academia and other sectors of society has widened, and it is critical to the long-term health of this institution that we continue to address this issue on a priority basis within our planning system. As this occurs it will be essential that the coupling of rewards to performance be emphasized in all sectors of the College as an important feature in our compensation program.

THE product of a quality faculty is a soundly conceived curriculum that addresses the purposes and goals of the institution. In a college dedicated to liberal arts education, tendencies toward overspecialization, excessive utilitarianism, and curricular discontinuities will not serve us well. We must always be willing to reassess academic programs against external criteria to assure that, insofar as possible, the cumulative experience of a Dartmouth education provides our graduates with a lifetime of fulfillment. In a changing world, our curriculum must preserve the value of historical lessons and great works while still incorporating the flexibility to respond to new issues and to develop new understandings understandings that are of sufficient depth to confront the complexities described by Richard Eberhart in his poem "Stopping a Kaleidoscope":

I stop it, and there I see the world of the present,Manifold reality fixed in a moment of time.I turn it. It will be the twenty-first century.

The merging of disciplines needed to respond to the challenges of worldwide alterations in social, economic, and political patterns must be reflected not only in the curriculum but also in how these academic activities are aligned. Our educational departments today are increasingly structured around strong academic centers centers which share a common bond of interest the Gilman Biomedical Center, the Hopkins Center and the planned Hood Museum for the performing and visual arts, and the Fairchild Center for Physical Sciences.

They will soon be joined by the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for the Social Sciences. It is not difficult to project further into the future and, based on faculty initiatives, conceive of a similar center for the humanities and other aggregations in arts and sciences, where the housing of several departments or disciplines under a common roof will reinforce a specific area of academic concentration. This same concept could be extended to other areas in the institution. A center in management and technology might well exist through a closer link between the Thayer School of Engineering and the Tuck School of Business Administration, and possibly a center for continuing education could also have institutional validity. The evolution of such aggregations linked together by the interests and pursuits of students and other members of the College community and supported by our exceptional system of libraries and computer capabilities will enhance our ability to respond to the growing need to recognize the interrelationships of traditional disciplines.

Responsibility for curriculum development must be coupled with a faculty structure that is conducive to meaningful academic planning. If we are to control and neutralize the factors that lead to the deterioration of academic quality, the institution must demonstrate the ability to respond competently to contemporary requirements. We must be willing to take risks in order to pioneer in developing innovative approaches at the frontiers of new knowledge and understanding. We can ill afford to polarize around the status quo in a changing world. We must demonstrate the wisdom to preserve the strengths of our existing curriculum, and, as we introduce new exciting offerings, we will need the discipline to identify and discard those components that command a lower academic priority. Only in this way can we keep Dartmouth at the forefront of an era of renewed appreciation of the vital role of the liberating arts.

Ernest Martin Hopkins wrote that "the goal of education is the cultivation and development of our mental powers to the end that we may know truth and conform to it." This pursuit must take place outside the classroom as well as within. The education of our students in its broadest sense is the duty of the entire Dartmouth family. The non-classroom component of residential college life should always be consistent with and complement our scholarly pursuit. It is the College's responsibility to provide facilities for this interaction to occur to strengthen the quality of the students' experience and to facilitate the development of the undergraduates' responsibility to themselves and to all others who share their surroundings.

I know of few areas in the Dartmouth fabric which need mending more than the quality of undergraduate life. The terrain between the classroom and the dormitory room needs to be filled with greater opportunities for intellectual growth and for the strengthening of healthy interpersonal relationships among students and among students, faculty, administrators, and our neighbors in the Upper Valley.

The privilege of attending Dartmouth is accorded to but few who apply. As such, the student bears a special responsibility as a scholar and as a member of the community to stretch to full height in harvesting Dartmouth's riches. While the student must till his own plot of ground, the College needs to prepare the field to make the conditions suitable for growth. Our commitment to excellence must extend to living accommodations as well as to social facilities. It must involve programs as well as buildings whether those programs take place in our fraternal organizations, in our cultural centers, on our athletic fields, or in the, mountains of New Hampshire. I know from firsthand experience how important this can be to attaining fulfillment through the Dartmouth experience.

If we fail to provide our students with the opportunities to raise moral consciousness and to sharpen ethical standards, then we will have surely failed in one of our primary obligations.

In a like sense, the positive steps over the past decade and a half to introduce greater diversity in the College population through our commitments to equal opportunity and affirmative action programs must be sustained. These commitments broaden each student's understanding of the needs and strengths of the other an understanding that is essential in those whose education will lead them into important roles in our society. This emphasis is in the oldest and finest tradition of the College.

John Kemeny provided great personal leadership in extending the initiatives of his predecessor by increasing the presence of minorities and the disadvantaged within the College community. We cannot let these efforts be altered by government policies or by lack of personal resolve. A continuation of our "need-blind" admissions policy will be an essential component of this effort. In pursuing this goal, we must also recognize and encourage access to the College by other members of emerging ethnic groups, such as Hispanics, who qualify for entry under our admissions standards. Enhancing the diversity of the institution and providing stewardship over the advancement opportunities for members of minority groups at all levels within the College is essential to achieving the full potential of the Dartmouth experience.

THE Dartmouth experience emanates from a sense of community which has characterized the College throughout its long history. It is manifest in this place, in the legendary Dartmouth spirit, in the life-long associations begun on the Hanover Plain, and in our extraordinary faith in the best of the traditions and the values of this college. It is a sense of community that runs between students and faculty, between faculty and alumni, and between thousands of Dartmouth men and women and their alma mater. Each has a responsibility to the other and to their college.

In the years ahead, Dartmouth, along with our sister institutions, will be faced with making hard choices between priorities which will often be mutually exclusive. As in the past, our route will be "the one less traveled by" the path of excellence, the path which leads to pre-eminence in liberal-arts education, the path traveled by those with a clear sense of purpose. These are the great traditions of the College and they will mark our course as we continue to move forward. It is a path not without risk, but the rewards for those who traverse its slopes are immense.

Our way is open to us through the sense of community which embodies the goodness and the grace of this great institution.

I would like to conclude on a somewhat more personal note. I have had the rare privilege in my lifetime to know Dartmouth as an undergraduate, as a graduate student, as an alumnus, and as a trustee. I have also had the great fortune to marry a woman who loves this place as I do, and together we have come to know the College in a new light as parents of a Dartmouth son and daughter.

As a student, I savored my courses in English, history, and government. I enjoyed music and the sciences. I suffered through French and grew under the stimulation of the Great Issues course. My experiences on Dartmouth's athletic fields were characterbuilding, and my love of her mountains is unending. I was in truth a "swinger of birches." I could drink deeply from Dartmouth's well of knowledge.

That opportunity was mine due to the generosity of generations of Dartmouth alumni and friends of the College who preceded me to Hanover. Their willingness to share with others not only made possible the great college I attended but also provided the scholarship support so that I could matriculate here.

In many respects, the Dartmouth of today is a better Dartmouth than the one I attended. With Judy's help, I pledge to leave to my successor a better Dartmouth than the one I am now charged to protect. That is the meaning of the Wheelock Succession.

In fulfilling that role I hope to assure that present generations of Dartmouth men and women will want to provide for their successors in the Dartmouth family just as others have done throughout our proud history.

Dartmouth with its special sense of place is a precious asset. In one of Goethe's great lines he wrote, "A man doesn't learn to understand anything unless he loves it." Loving Dartmouth is a joyful experience. That experience is ours, but it can only come from understanding understanding each other and understanding our College. In that direction lies our destiny.

It is now time to begin. We have an exciting and rigorous path to travel, so let us resume our journey to the accompaniment of our founder's motto: Vox Clamantis in Deserto.

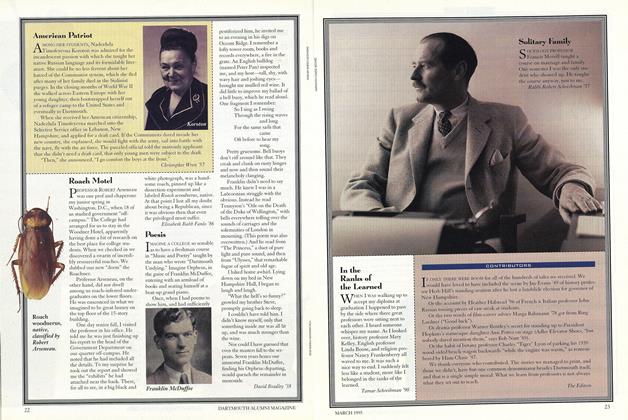

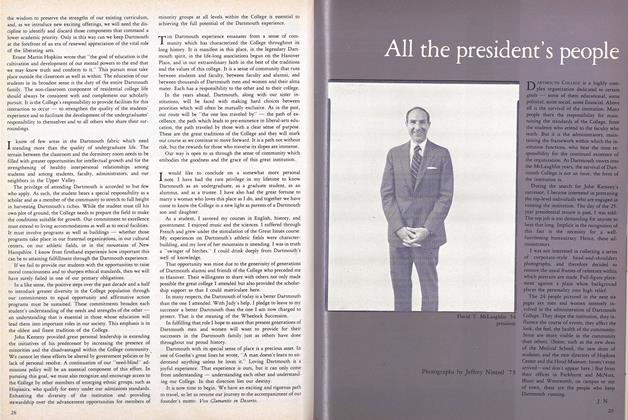

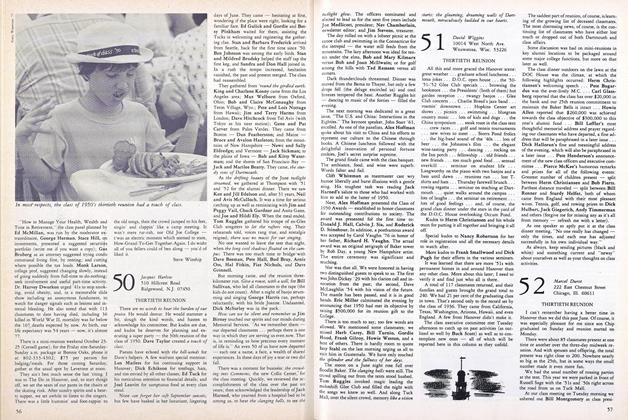

Kemeny and McLaughlin (opposite)joyfully ascend the steps of Parkhurst Hallfollowing the inaugural ceremony. Encomiums were the order of the day as JudyMcLaughlin and Jean Kemeny (above)saluted Christina Dickey and well-wishersin the audience (below) fervently applaudedthe speech-makers.

Kemeny and McLaughlin (opposite)joyfully ascend the steps of Parkhurst Hallfollowing the inaugural ceremony. Encomiums were the order of the day as JudyMcLaughlin and Jean Kemeny (above)saluted Christina Dickey and well-wishersin the audience (below) fervently applaudedthe speech-makers.

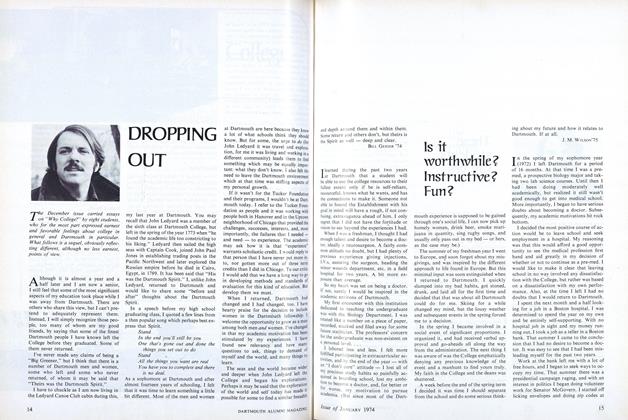

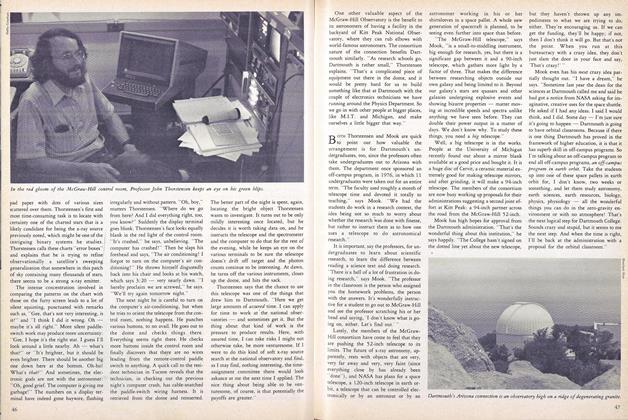

The 14th president, wearing the Flude Medal, receives a warm handshake from the 13 thOpposite: overlooking Baker lawn, David McLaughlin delivers his inaugural address.

Inaugural address

McLaughlin, Kemeny, Dickey: "a succession honoring the founder."

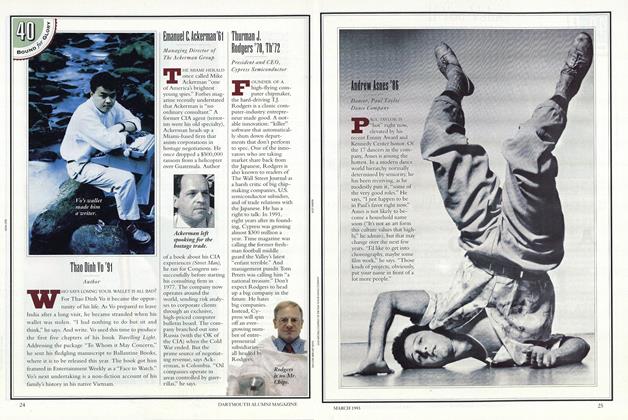

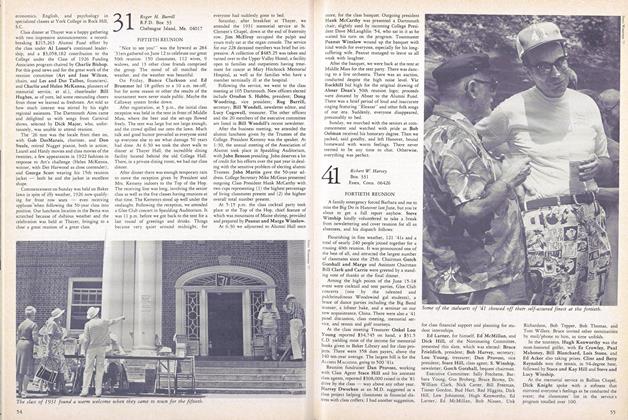

Phalanx ofpresidents: inaugural guests {top row, from left) Handler of the University of New Hampshire, Gray of M.I. T. Campbell ofWesleyan, Ashby of Pine Manor, Chandler of Williams, Swearer of Brown; (middle) Kenan of Aft Holyoke, Johns of Wellesley,Horner of Radcliffe, Conway of Smith; (bottom) McLaughlin and Kemeny, and Giamatti of Yale.

Fixed reality and the changing order

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

September 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureAll the Presidents's People

September 1981 By J. N. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

September 1981 By Clement B. Malin -

Article

ArticleHistory Without Battles

September 1981 By Beth Ann Baron '80 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

September 1981 By Jacques Harlow -

Sports

SportsMany Are Called

September 1981 By Brad Hills '65