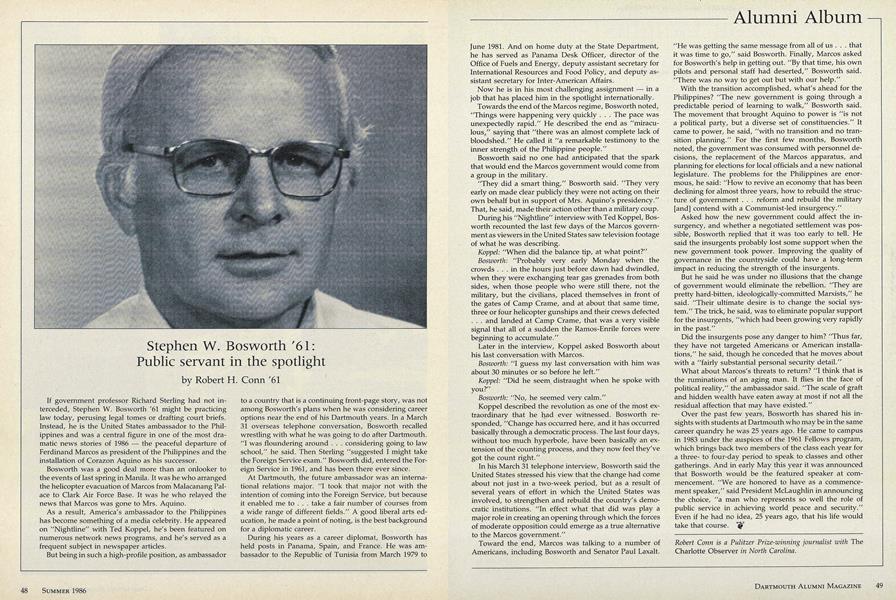

If government professor Richard Sterling had not interceded, Stephen W. Bosworth '61 might be practicing law today, perusing legal tomes or drafting court briefs. Instead, he is the United States ambassador to the Philippines and was a central figure in one of the most dramatic news stories of 1986 the peaceful departure of Ferdinand Marcos as president of the Philippines and the installation of Corazon Aquino as his successor.

Bosworth was a good deal more than an onlooker to the events of last spring in Manila. It was he who arranged the helicopter evacuation of Marcos from Malacanang Palace to Clark Air Force Base. It was he who relayed the news that Marcos was gone to Mrs. Aquino.

As a result, America's ambassador to the Philippines has become something of a media celebrity. He appeared on "Nightline" with Ted Koppel, he's been featured on numerous network news programs, and he's served as a frequent subject in newspaper articles.

But being in such a high-profile position, as ambassador to a country that is a continuing front-page story, was not among Bosworth's plans when he was considering career options near the end of his Dartmouth years. In a March 31 overseas telephone conversation, Bosworth recalled wrestling with what he was going to do after Dartmouth. "I was floundering around . . . considering going to law school," he said. Then Sterling "suggested I might take the Foreign Service exam." Bosworth did, entered the Foreign Service in 1961, and has been there ever since.

At Dartmouth, the future ambassador was an international relations major. "I took that major not with the intention of coming into the Foreign Service, but because it enabled me to . . . take a fair number of courses from a wide range of different fields." A good liberal arts education, he made a point of noting, is the best background for a diplomatic career.

During his years as a career diplomat, Bosworth has held posts in Panama, Spain, and France. He was ambassador to the Republic of Tunisia from March 1979 to June 1981. And on home duty at the State Department, he has served as Panama Desk Officer, director of the Office of Fuels and Energy, deputy assistant secretary for International Resources and Food Policy, and deputy assistant secretary for Inter-American Affairs.

Now he is in his most challenging assignment - in a job that has placed him in the spotlight internationally. Towards the end of the Marcos regime, Bosworth noted, "Things were happening very quickly . . . The pace was unexpectedly rapid." He described the end as "miraculous," saying that "there was an almost complete lack of bloodshed." He called it "a remarkable testimony to the inner strength of the Philippine people."

Bosworth said no one had anticipated that the spark that would end the Marcos government would come from a group in the military.

"They did a smart thing," Bosworth said. "They very early on made clear publicly they were not acting on their own behalf but in support of Mrs. Aquino's presidency." That, he said, made their action other than a military coup.

During his "Nightline" interview with Ted Koppel, Bosworth recounted the last few days of the Marcos government as viewers in the United States saw television footage of what he was describing.

Koppel: "When did the balance tip, at what point?" Bosworth: "Probably very early Monday when the crowds ... in the hours just before dawn had dwindled, when they were exchanging tear gas grenades from both sides, when those people who were still there, not the military, but the civilians, placed themselves in front of the gates of Camp Crame, and at about that same time, three or four helicopter gunships and their crews defected . . . and landed at Camp Crame, that was a very visible signal that all of a sudden the Ramos-Enrile forces were beginning to accumulate."

Later in the interview, Koppel asked Bosworth about his last conversation with Marcos. Bosworth: "I guess my last conversation with him was about 30 minutes or so before he left."

Koppel: "Did he seem distraught when he spoke with you?" Bosworth: "No, he seemed very calm."

Koppel described the revolution as one of the most extraordinary that he had ever witnessed. Bosworth responded, "Change has occurred here, and it has occurred basically through a democratic process. The last four days, without too much hyperbole, have been basically an extension of the counting process, and they now feel they've got the count right."

In his March 31 telephone interview, Bosworth said the United States stressed his view that the change had come about not just in a two-week period, but as a result of several years of effort in which the United States was involved, to strengthen and rebuild the country's democratic institutions. "In effect what that did was play a major role in creating an opening through which the forces of moderate opposition could emerge as a true alternative to the Marcos government."

Toward the end, Marcos was talking to a number of Americans, including Bosworth and Senator Paul Laxalt. "He was getting the same message from all of us . . . that it was time to go," said Bosworth. Finally, Marcos asked for Bosworth's help in getting out. "By that time, his own pilots and personal staff had deserted," Bosworth said. "There was no way to get out but with our help."

With the transition accomplished, what's ahead for the Philippines? "The new government is going through a predictable period of learning to walk," Bosworth said. The movement that brought Aquino to power is "is not a political party, but a diverse set of constituencies." It came to power, he said, "with no transition and no transition planning." For the first few months, Bosworth noted, the government was consumed with personnel decisions, the replacement of the Marcos apparatus, and planning for elections for local officials and a new national legislature. The problems for the Philippines are enormous, he said: "How to revive an economy that has been declining for almost three years, how to rebuild the structure of government . . . reform and rebuild the military [and] contend with a Communist-led insurgency."

Asked how the new government could affect the insurgency, and whether a negotiated settlement was possible, Bosworth replied that it was too early to tell. He said the insurgents probably lost some support when the new government took power. Improving the quality of governance in the countryside could have a long-term impact in reducing the strength of the insurgents.

But he said he was under no illusions that the change of government would eliminate the rebellion. "They are pretty hard-bitten, ideologically-committed Marxists," he said. "Their ultimate desire is to change the social system." The trick, he said, was to eliminate popular support for the insurgents, "which had been growing very rapidly in the past."

Did the insurgents pose any danger to him? "Thus far, they have not targeted Americans or American installations," he said, though he conceded that he moves about with a "fairly substantial personal security detail."

What about Marcos's threats to return? "I think that is the ruminations of an aging man. It flies in the face of political reality," the ambassador said. "The scale of graft and hidden wealth have eaten away at most if not all the residual affection that may have existed."

Over the past few years, Bosworth has shared his insights with students at Dartmouth who may be in the same career quandry he was 25 years ago. He came to campus in 1983 under the auspices of the 1961 Fellows program, which brings back two members of the class each year for a three- to four-day period to speak to classes and other gatherings. And in early May this year it was announced that Bosworth would be the featured speaker at commencement. "We are honored to have as a commencement speaker," said President McLaughlin in announcing the choice, "a man who represents so well the role of public service in achieving world peace and security." Even if he had no idea, 25 years ago, that his life would take that course. Iff

Robert Conn is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist with The Charlotte Observer in North Carolina.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

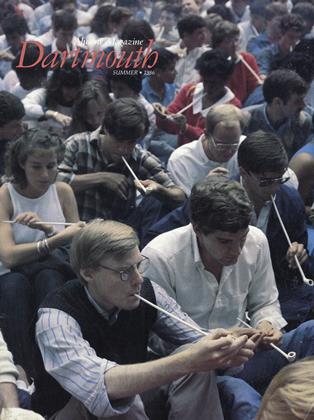

FeatureYou Laughed

June 1986 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT

June 1986 -

Feature

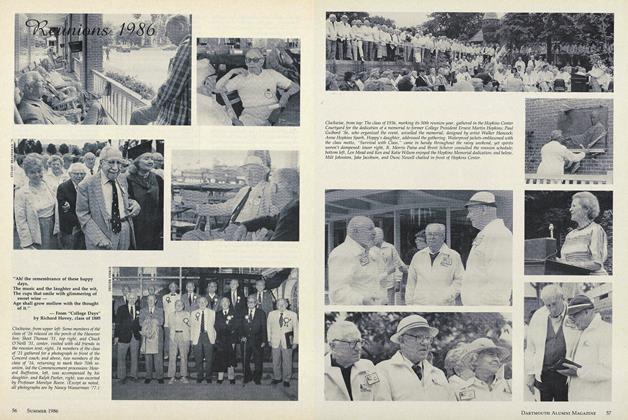

FeatureReunions 1986

June 1986 By Richard Hovey -

Article

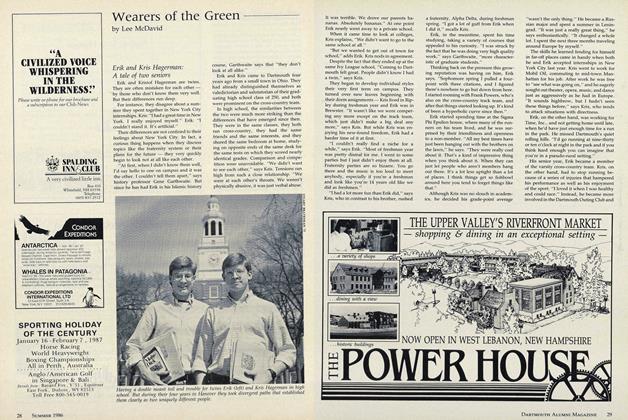

ArticleErik and Kris Hagerman: A tale of two seniors

June 1986 By Lee McDavid -

Article

Article"More than Teacher"

June 1986 By Dorothy L. Foley '86 -

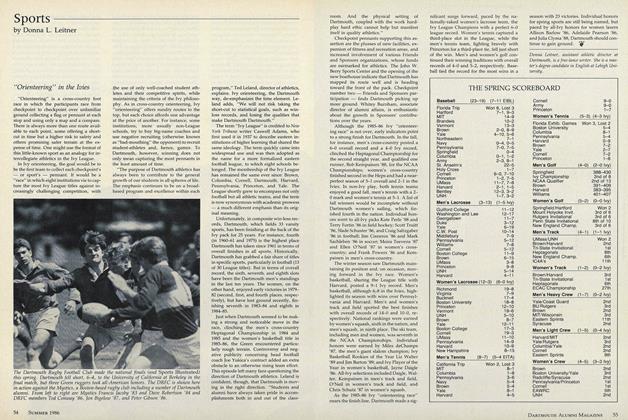

Sports

Sports"Orienteering" in the Ivies

June 1986 By Donna L. Leitner