My mother is an elementary school principal and was a teacher for many years before that. She has long been amused by her students' reactions when they see her outside of the school. Occasionally, a pupil will come up to her in the supermarket and exclaim, wide-eyed, "Mrs. Foley, why are you grocery shopping?" (Thinking, I suppose, either that she stays in school all night and dines on leftovers from the cafeteria, or that she comes home, presses a button a la TV's Jetson family, and eats a complete dinner prepared by a little machine in the kitchen wall after all, teachers can do anything.) Although we college students are not usually so awestruck by our professors, we have some equally absurd misconceptions.

For example, many students don't understand the role of faculty research. But that's only natural, when normally we see faculty just in the classroom and not at work on their books or articles in progress. It's easy for us to forget that much faculty time is devoted to research and to wonder why faculty feel compelled to write. "Students often feel a great mystery about what the faculty 'do' and about the role of faculty research," according to Associate Professor of English David Kastan. "The tendency of students, especially when tenure decisions are handed down, is to say, 'Why didn't Professor X get tenure just because he or she didn't publish? After all, what does publishing have to with teaching?' " Kastan thinks that, in the long run, research has a great deal to do with teaching.

But many people in academia feel that teaching is a gift. If that is so if teaching is an innate skill then no amount of research and writing would make a good teacher. We've all heard about professors whose books were shatteringly brilliant but whose lectures were so boring and monotonous that nine out of ten students would have preferred watching test patterns on a television screen. However, we have to recognize the fact that research and writing cannot help but add more energy and enthusiasm to even the most sparkling lectures and, furthermore, that good teachers must engage in research in order to keep their teaching insightful and dynamic. In fact, what goes on in faculty studies is not irrelevant to what occurs in classrooms. Says Professor Kastan, "Anyone whose research is truly vital will find that the research feeds into his or her teaching, and vice versa. The teacher's energy and excitement about his research gives him new ideas and enthusiasm in his classes, and the questions and responses of the students to the professor's ideas stimulate further thought in the research." Without research, Professor Kastan maintains, the depth of interchange is limited, the teacher does not as readily reconsider old ideas and formulate new ones, and the quality of his or her teaching almost inevitably deteriorates.

Nancy Vickers, associate professor of French and Italian, agrees. "Academicians are fossilized without research our teaching would stagnate without it." Professors Kastan and Vickers are team-teaching a comparative literature/women's studies course called "Renaissance Woman/Renaissance Man," exploring the roles of men and women in the Renaissance and asking "Did women have a Renaissance?" Professor Vickers is currently researching the court of the French king, Francis I. "What I'm trying to do is to look at both poetry and the visual arts, attempting to locate works of art in their political, social, cultural, and historical context while at the same time putting the issue of gender into those contexts. I'm looking at the ways, for example, that Francis I articulates his political power by using gender-specific images. One question this leads to is what was it like to be an artist working for a king who was trying to define art to impose the sense of his power?" Vickers's work, according to Kastan, is "opening new doors in Renaissance criticism." Two weeks of "Renaissance Woman/Renaissance Man" are spent discussing the court of Francis I. Says Vickers, "Every time I teach something that I'm researching, the students' questions help me see my own work in a very different light. The questions on Francis I, for example, really helped me clarify my thinking. So [the relationship of research to teaching] is a two-way street: the researcher brings new ideas and theories to teaching and the class provides responses and new ideas for the researcher."

Faculty research is propelling Dartmouth into the forefront of many fields. For example, the past two issues of The Journal ofEnglish Literary History, one of the most prestigious journals of literary criticism, have each contained two articles by faculty members from Dartmouth the only institution represented more than once.

Professor Kastan's Shakespeare research, according to the prominent University of Chicago Shakespeare critic David Bevington, "approaches genre classification in a way I've never seen before" and has earned Kastan a place on the prestigious Shakespeare Executive Board of the Modern Language Association. Many other faculty members are winning similar accolades for their research. The very high regard which researchers at other institutions have for work of Dartmouth faculty has led to Dartmouth's being chosen as the site for major colloquiums, such as the School for Criticism and the Dante Institute. The Dante Institute is an intensive six-week summer program for non-Dante specialists - professors from all over the country - who teach Dante in western civilization, history, and other courses. "It is entirely supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, which asked Dartmouth to organize the institute as a result of the Dante Project," says Professor Vickers. The Dante Project is an effort to put all of the commentaries about The Divine Comedy on a computer. Professor Vickers feels that "the Dante Project is going to be a research tool for generations of Dante scholars. It will totally reshape the face of Dante scholarship by giving researchers the kind of access to the material that has never before been available. I can't think of any place in the country where it's more exciting to be a Dante scholar."

Many professors feel that teaching at Dartmouth puts them in a unique, but difficult, position. On the one hand, they are expected to be prominent professionally to publish "significantly" both quality- and quantity-wise. On the other hand, they are expected, because of Dartmouth's tradition of excellent teaching and close faculty involvement with students, to excel in the classroom and to become involved in student life. "Dartmouth sees itself somewhat schizophrenically: both as a major research institution and as a small liberal arts college," explains Professor Kastan. "The demand this makes on the professors is a major source of tension and anxiety among the faculty. Of course, this same doubleimage is one of the wonderful things about Dartmouth." Adds Professor Vickers, "The Dartmouth faculty has the professional demands of the other Ivies but has the teaching load, student involvement, and committee work of such small institutions as Amherst or Williams." Either of those aspects is a full-time job at other institutions.

In the end, though, the unique demands placed on the Dartmouth faculty may make Dartmouth professors even better role models for students. In some way, all of us face or will face some sort of double role in life: to write and teach, to pursue our careers while maintaining our obligations to our families, to help our companies grow and prosper while making certain that business decisions are ethical and fair to consumers and employees, or to win a political race while retaining idealism and a commitment to public service.

There are other ramifications of research and teaching. The Dartmouth faculty research creates a stimulating environment for students, an environment that Professor Kastan says most students "don't take advantage of because of the 'work hard/play hard' ethos of Dartmouth. However, the rewards for those who do take advantage of the faculty are great; Dartmouth undergraduates have opportunities for working with a professor that at other institutions are reserved for graduate students."

The faculty's commitment to research and publishing in order to stimulate their teaching makes one think about the roles analysis and writing play in all of our lives. The Puritan writer and minister Cotton Mather wrote that the study of literature "may a little sharpen your senses." Research and writing not only help us clarify our ideas, they help us express ourselves with clarity and style on other subjects. That is one of the meanings, I believe, of the phrase, "a liberal arts education helps one to think." Good writing is highly valued today. According to law schools and businesses, for example, very few applicants can communicate effectively. Even more important than that, however, is that research and writing on one subject almost inevitably lead to an application of the same ideas to other issues. Perhaps, then, as Keats and Shelley may have felt, writing is a search for truth. Therefore, research and writing combined with excellent teaching must be something even greater than a search for truth. As Kierkegaard wrote, "One who gives the learner not only the Truth, but also the condition for understanding it, is more than Teacher."

Dottie Foley, one of the Magazine's undergraduate interns for 1985-86, has spent muchof the last year as a senior fellow, researching aplay about poet Edna St. Vincent Millay.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

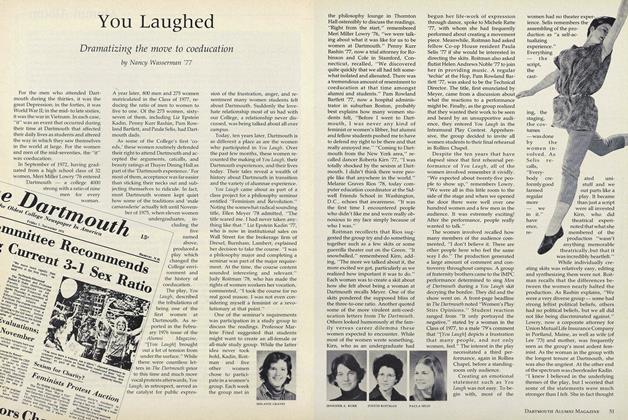

FeatureYou Laughed

June 1986 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

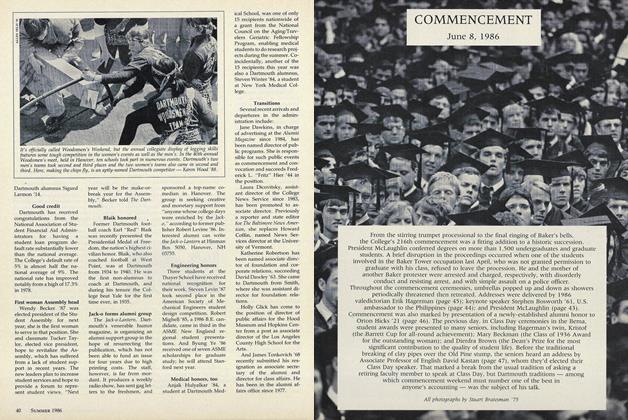

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT

June 1986 -

Feature

FeatureReunions 1986

June 1986 By Richard Hovey -

Article

ArticleErik and Kris Hagerman: A tale of two seniors

June 1986 By Lee McDavid -

Article

ArticleStephen W. Bosworth '61: Public servant in the spotlight

June 1986 By Robert H. Conn '61 -

Sports

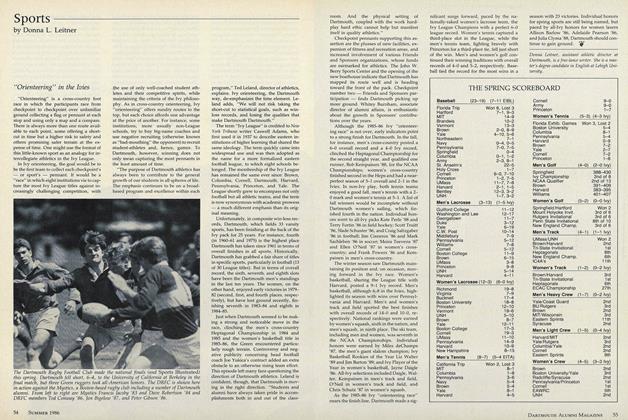

Sports"Orienteering" in the Ivies

June 1986 By Donna L. Leitner