As the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged 508.32 points last October 19, college and university endowments across the land suffered. Some institutions lost more than 16 percent of their endowments, while Harvard's dipped by just seven percent. Dartmouth lost less than ten. As this issue went to press in January, however, College officials were still nervous about the longterm effects of the crash.

Dartmouth's investment strategists attribute the endowment's reasonably successful weathering of Black Monday to two principal factors: a well-diversified portfolio, and portfolio-protection measures.

The endowment comprises 35 percent fixed-income securities (such as government bonds), which are relatively unaffected by market fluctuations; and 65 percent equities, whose value is tied to the market. The equity portion is divided among real estate, foreign securities, venture capital, and large and small capital stocks.

Dartmouth's financial stability was helped also by well-timed caution, according to Robert E. Field '43 T'47, vice president and treasurer of the College. Last spring, Field explained, the Trustees became concerned that the market was overpriced, and they implemented a "portfolio protection insurance plan." "The plan protects the endowment portfolio by employing a sophisticated and exotic technique of making forward sales of future options and indexes," said Field.

The College's fundamental strategy is one commonly employed as a temporary fail-safe measure by pessimistic investors. It is based on predictions of stocks' prices at an agreed-upon date. For example, an investor might base an index on stock ycurrent price, $100—and estimate that it will be worth $105 three months hence. If in three months stock y has gone up to $115, the investor owes $10—the difference between y's actual value and the value the investor had predicted. If, on the other hand, the value of the stock y has declined to $80, the investor collects $20. The strategy ensures that, at the end of the period, the portfolio has retained its original value without the investor's having to sell off stock.

"What we did," explained Field, "was protect ourselves on the low side, and give up something on the up side, in order to guard against a drastic decline in the market." He added: "The reason that the portfolio insurance protection plan did not work perfectly is that the market on October 19 was so chaotic that it was not possible to make the necessary trades in options and futures to protect ourselves completely."

Nonetheless, the endowment's dip will have little immediate effect on the College's budget, officials say. In typical years, the endowment supplies 13 to 14 percent of operating revenue, with the rest coming from tuition, faculty grants and gifts. Exact dollar amounts, according to Field, are determined by a spending formula that includes "a smoothing factor that largely insulates the budget from year-to-year fluctuations in endowment value." As a result, next year's overall budget is unlikely to suffer by more than one tenth of one percent from Black Monday's impact on the endowment.

Field notes, however, that the market crash may have more dire effects next fiscal year: the remaining 86 to 87 percent of the budget is drawn from other sources—notably gifts—whose vulnerability to the market remains to be seen.

"Are people going to be less inclined to give because they feel poorer from the stock market debacle?" offers Field. "I'm sure there will be some effect, but I think it's largely psychological. If you took a snapshot of the market today, and where it was only a little over a year ago, you'd think nothing extraordinary had happened."

The mood did indeed look bad when this was written in early winter. Director of the Bequests and Trusts Program Frank A. Logan '52 noted that the number of year-end "life income" gifts of securities was down rather significantly. Logan further commented that donors will probably have to work their way through a lot of nervousness before such giving returns to a more normal level." On the other hand, gifts to the 1988 Alumni Fund, which are usually made from income rather than capital, remained brisk."—Tim Burger '88

Karen Avenoso '88, an English major and an undergraduate representative to theAlumni Council, was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship. She is the second Dartmouthwoman to be honored.

"If I had a pipe dream, I'd like to Abe the Abraham Lincoln of Dartmouth—to heal the warring factions." —President Freedman in a Boston Globe interview. "Most everyone who lives, or has lived, in New England knows a former Dartmouth skier. He's the one who skis in old equipment, baggy pants and roomy parkas—and speeds downhill embarrassingly faster than the rest of the pack trailing with its high-tech gear." —Ski Magazine, December '87

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

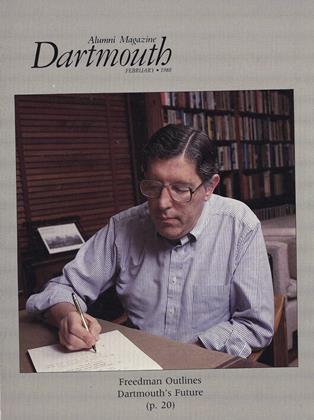

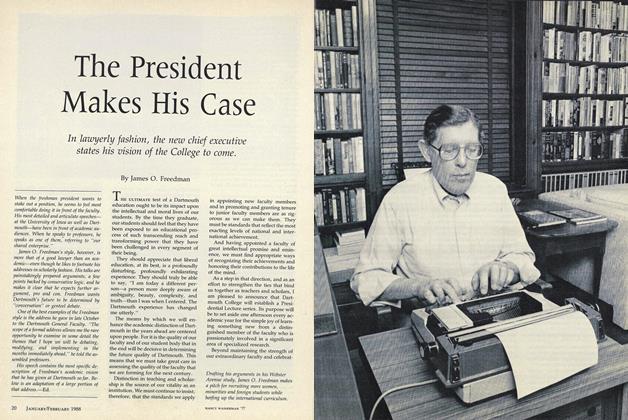

Cover StoryThe President Makes His Case

February 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

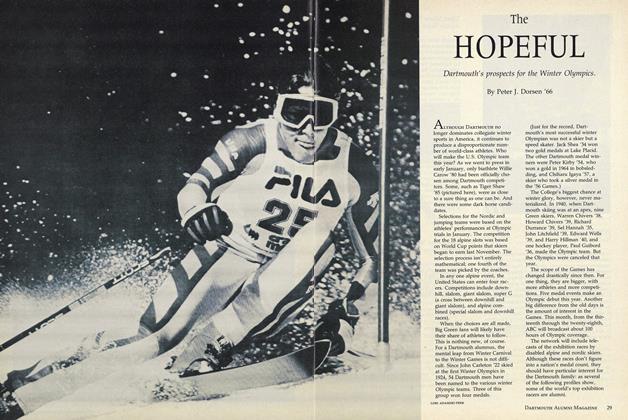

FeatureTHE HOPEFUL

February 1988 By Peter J. Dorsen '66 -

Feature

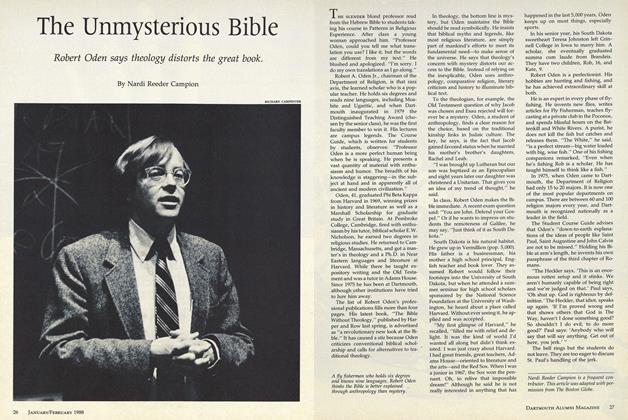

FeatureThe Unmysterious Bible

February 1988 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Sports

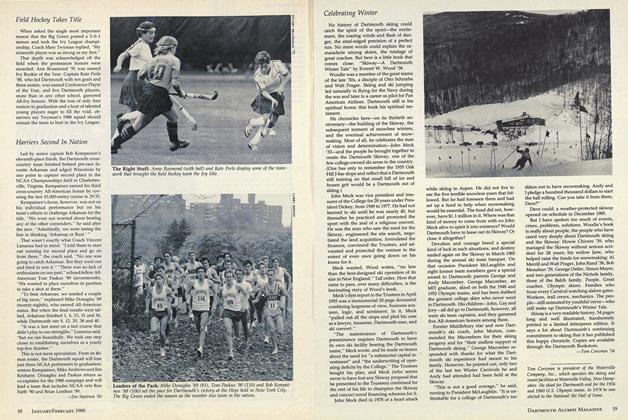

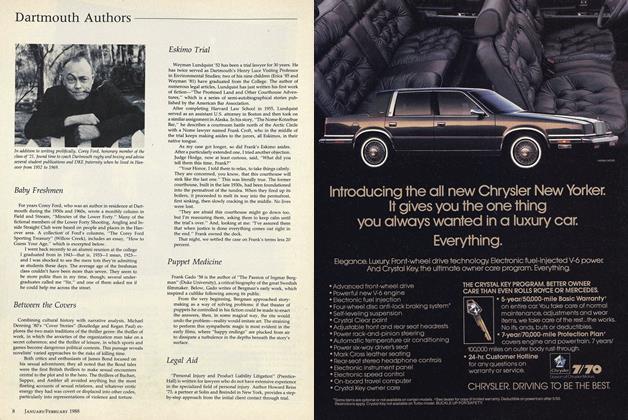

SportsCelebrating Winter

February 1988 By Tom Corcoran '54 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

February 1988 -

Article

ArticleFour Alumni Authors from the '40s to the '80s

February 1988

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe Old Reservoir subsequent to its enlargement

April 1926 -

Article

ArticleCourses Accredited

December 1940 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

Jan/Feb 2005 -

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

March 1943 By Dartmouth -

Article

ArticleCLASS OF 1870

June 1916 By Lemuel S. -

Article

ArticleTHE NATURE OF FASCISM

January 1948 By LEWIS MUMFORD