In lawyerly fashion, the new chief executive states his vision of the College to come.

THE ULTIMATE test of a Dartmouth education ought to be its impact upon the intellectual and moral lives of our students. By the time they graduate, our students should feel that they have been exposed to an educational process of such transcending reach and transforming power that they have been challenged in every segment of their being.

They should appreciate that liberal education, at its best, is a profoundly disturbing, profoundly exhilarating experience. They should truly be able to say, "I am today a different person—a person more deeply aware of ambiguity, beauty, complexity, and truth—than I was when I entered. The Dartmouth experience has changed me utterly."

The means by which we will enhance the academic distinction of Dartmouth in the years ahead are centered upon people. For it is the quality of our faculty and of our student body that in the end will be decisive in determining the future quality of Dartmouth. This means that we must take great care in assessing the quality of the faculty that we are forming for the next century.

Distinction in teaching and scholarship is the source of our vitality as an institution. We must continue to insist, therefore, that the standards we apply in appointing new faculty members and in promoting and granting tenure to junior faculty members are as rigorous as we can make them. They must be standards that reflect the most exacting levels of national and international achievement.

And having appointed a faculty of great intellectual promise and eminence, we must find appropriate ways of recognizing their achievements and honoring their contributions to the life of the mind.

As a step in that direction, and as an effort to strengthen the ties that bind us together as teachers and scholars, I am pleased to announce that Dartmouth College will establish a Presidential Lecture series. Its purpose will be to set aside one afternoon every academic year for the simple joy of learning something new from a distinguished member of the faculty who is passionately involved in a significant area of specialized research.

Beyond maintaining the strength of our extraordinary faculty and celebrat- ing its achievements, one of the most important tasks facing Dartmouth College in the years ahead will be to assemble the most gifted student body in the country—a student body of men and women with inquisitive minds and aspirations that are academic, artistic, cultural, moral, scientific, and, most of all, deeply intellectual.

For one who has only recently joined the Dartmouth community, my most persistent source of frustration has been the stereotype that too often is invoked to describe Dartmouth students, the stereotype that regards them primarily as extroverted, gregarious, party-going, athletically oriented, overly prone to conformity, well rounded, and intelligent but not intellectual.

Indeed, the leading commercially published guidebook for secondary school students says of Dartmouth that "most undergraduates are gearing up for remunerative careers." And it adds, "Dartmouth is no place for . . . sensitive intellectuals."

Embedded in that stereotypewhether it ever was accurate or notare a number of premises that have no place at today's Dartmouth. The first is that Dartmouth is not a hospitable environment for highly intellectual students, including students whom I described in my inaugural address as creative loners, daring dreamers, and young men and women who march to a different drummer. The second premise is that Dartmouth is not a hospitable environment for women. And the third is that Dartmouth is a place where, always and ever, "boys will be boys."

That shopworn stereotype is harmful to all of our academic aspirations for the College. It embodies a vestige of a style of collegiate life that we can no longer permit to reflect the Dartmouth of today. We need to make Dartmouth hospitable to the most intellectual and academic of studentsand especially to women and members of minority groups—and to make certain that the reality of our collegiate life fully reflects that hospitality.

The obligation to do so rests heavily upon the faculty, but it is also the task of our students. The power of peers to legitimate the choice of students to immerse themselves in intellectual pursuits without the fear of social reproach or embarrassment may be even greater than that of the faculty.

It is our students who can perhaps be the most effective shapers of an environment that is tolerant of individual differences, most especially differences in intellectual styles and interests, an environment in which students can feel entirely comfortable in choosing to devote an even greater share of their time and energies to the life of the mind than the majority of their classmates may.

I hope that in the years ahead we will assemble a student body even stronger academically than our present one, and that we will induce even more of the most gifted secondary school students in the nation to think of Dartmouth as one of the handful of institutions at which their intellectual and academic talents can best be nurtured.

Dartmouth has every reason to be proud of the quality of the students it now attracts, but for an institution of our intellectual aspirations, we still do not enroll a sufficient number of students of peak achievement—National Merit Scholars, Westinghouse Science winners, high school valedictorians.

In the course of this process of enriching Dartmouth's store of intellectual quality, we need not lose sight of the desirability of attracting those wellrounded students who add solid qualities to any institution. But it is important to remember, as one wag has said, that an institution can be so wellrounded that it lacks any point at all.

An essential part of attracting the most academically gifted students to Dartmouth will be to emphasize our efforts to enroll more women. The simple fact is that the current imbalance in the ratio between men and women at Dartmouth is not healthy for either the intellectual or the social life of the College. The sooner that we approach parity in the number of male and female students we enroll, as the Medical School already has, the sooner we will attain the greater academic distinction that we seek.

We have done well in attracting minority students to our freshman class—students who contribute in countless ways to the diversity and excellence of our enterprise. We must continue our efforts to recruit and attract a diverse mix of minority students to the undergraduate, graduate, and professional school programs, and we must do so with vigor.

Finally, we have an opportunity to examine our enrollment of foreign students in order to determine, from an educational point of view, what the proper percentage and geographic distribution of such students should be.

Although the undergraduate enrollment of foreign students is up, many significant countries are not represented by a single student in the freshman class—important countries such as France, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Egypt, Brazil, and Japan. And the number and percentage of foreign students at Dartmouth rank us near the bottom of our sister institutions in the Ivy League.

Foreign students can play an important role in helping us to nurture an international dimension at Dartmouth. We will benefit as a college by addressing the issues that attend the admission of foreign students and the contributions they make to the educational process.

As we seek to enhance the academic distinction of Dartmouth, I hope that we will find new ways to acknowledge the academic achievements of outstanding students at the College, and, more importantly, ways of motivating more students to consider careers of intellectual inquiry and artistic contribution.

Several trends warrant our collective attention. First, Dartmouth students historically have not aspired to their fair share of the honors awarded annually to outstanding college seniors in this country—honors such as Rhodes Scholarships, Fulbright Scholarships, Mellon Fellowships in the Humanities, Harry S. Truman Scholarships, Marshall Scholarships, and many others. Second, a lower percentage of Dartmouth graduates historically have sought Ph.D.'s—and therefore careers in the academic world, the sciences, and the visual and performing arts—than have graduates of most of the leading institutions with which we compare ourselves.

Dartmouth has every reason to be proud of the high percentage of its undergraduates who pursue careers in law, medicine, business, and the professions. But as we seek to strengthen the intellectual environment of the College, from the classroom to the residence halls, I hope that we will find ways to motivate more of our students to seek outstanding national honors upon graduation—honors to which their college records fully entitle them—and to follow careers that will increase the contributions that Dartmouth graduates make to academic life, to the sciences, and to the visual and performing arts.

I want now to turn to a particular area to which I hope Dartmouth will continue to give great emphasis in the years ahead; the area of international education.

Because the fortunes of this country are tied inextricably to conditions in the many nations of the world, it is essential that colleges of liberal learning bring a global perspective to their curricula so that students can appreciate eastern civilization no less than western civilization and can comprehend the awful complexities and promising subtleties of the international environment.

From Aquinas and Bacon to Jefferson and Newman, no conception has been more firmly embedded in the way in which higher education has organized knowledge than the emphasis it has given to the values of western civilization. In a number of public addresses in recent years, I have asserted that a liberal education is "the surest instrument that western civilization has yet devised for preparing men and women to lead productive and satisfying lives." Yet looking back, I wonder now whether that confident declaration was not too narrowly framed.

To the extent that an unqualified emphasis upon "western civilization" blocks access to non-western civilization, it legitimates an assumption of European and American cultural superiority that will not withstand analysis. That assumption is as damaging to our students individually as it is menacing to the world they will be compelled to understand and to shape.

As a corrective to our conventional emphasis upon western civilization, we need only recall the twelfth-century European discovery of scientific and mathematical works written in Arabic. It was not political or geographical barriers that had kept western scholars from this body of knowledge until the time of the Crusades. Rather, it was a psychological and cultural indifference to non-western achievements.

Without the development of algebra, to say nothing of the concept of the zero and the Arabic numerals themselves, modern western advances in mathematics and sciences would be, quite literally, unthinkable. Less than a hundred years after the project of translating Arabic texts began, European scholars were able to enjoy the fruit of thousands of years of Middle Eastern studies in medicine, biology, mathematics, physics, and astronomy.

Newton was right in saying, "If I have seen farther, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants." We must remind ourselves and our students, as we seek to organize knowledge, that the sturdy feet of some of those giants were planted firmly in the East.

Of course it is important that students of successive generations appreciate and possess the western tradition. It is the very creator of our culture. But it is essential, too, that students recognize that the western tradition is only one of the world's great cultural traditions. There are traditions in Asia, in Africa, in the Islamic world, in Latin and South America, which must command our attention because they, too, have shaped the world our students will inherit. We must enlarge the opportunities we offer our students to explore these traditions.

The understanding of other cultural traditions begins with language. One of the United States' most distressing deficiencies is our growing inability to communicate with the other nations of the world because of a lack of proficiency in their languages. The study of a nation's language often reveals the values of a foreign culture more tellingly than a dozen treatises. It illustrates the intimate bonding that exists between style and content, between cadence and substance, between idiom and national character. It makes clear that human beings are as much the creatures of their language as they are its makers.

It is only in recent years that the United States has recognized that strong foreign language skills, coupled with a willingness to learn about other cultures, helps to account for the phenomenal success of the Japanese in capturing such a large market share for so many of their products in this country and around the world.

Our national interest, both economically and politically, requires that we develop a versatile competence in foreign languages. Yet we have made little progress as a nation in doing so.

Indeed, at the time of the war in Vietnam, not a single American-born specialist on Vietnam, Cambodia, or Laos was teaching in an American university or working in the State Department. And at the time of the revolution in Iran, only six of the 60 foreign service officers assigned to the United States Embassy in Teheran were even minimally proficient in Farsi, the language that Iranians speak. In both instances, the United States was compelled to make foreign policy in a cultural vacuum.

Moreover, as the locus of world politics and international trade is shifting from countries that speak English, Spanish, German, and French to countries that speak Russian, Chinese, Japanese, and Arabic, the United States is failing to keep pace in the education of men and women who can read and speak these languages.

That is why it is significant that Dartmouth has begun the teaching of Arabic this year and why it is essential that the teaching of Japanese begin at Dartmouth as soon as practicable, and thereby complement our already strong program in Chinese.

It would be easier for all of us, of course, to continue insisting that the rest of the world learn English. But such an expectation has already placed Americans at a serious disadvantage in the international marketplace and at an even more serious disadvantage in diplomatic affairs.

By expecting others to learn our language while we do not attempt to learn theirs, we are isolating ourselves from a wide range of opportunities—diplomatic, economic, and cultural. We are limiting our capacity to trade in ideas no less than in services and products.

Dartmouth has a strong record of achievement in foreign language instruction and in international education. Few institutions provide such extensive opportunities for their students to spend an academic term in a foreign country. In addition, Dartmouth requires all students to complete a course that focuses upon a subject derived from non-western sources.

We must continue to build upon this strength as we help students to understand the values that other nations hold and the customs they follow. In so doing, we will not only deepen our students' understanding of the world, we will also help to reduce the misconceptions that so frequently result from cultural differences and perhaps even contribute to a firmer foundation of international trust.

We still do not enroll enough "students of peak achievement," writes Freedman

"My most persistentsource of frustration hasbeen the stereotype thattoo often is invoked todescribe Dartmouthstudents."

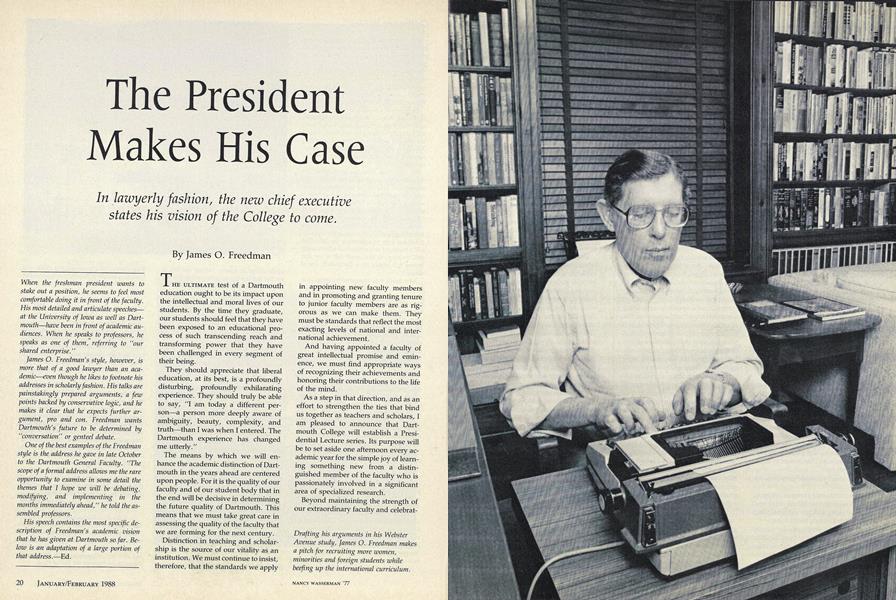

When the freshman president wants tostake out a position, he seems to feel mostcomfortable doing it in front of the faculty.His most detailed and articulate speechesat the University of lowa as well as Dartmouth—have been in front of academic audiences. When he speaks to professors, hespeaks as one of them, referring to "ourshared enterprise

James O. Freedman's style, however, ismore that of a good lawyer than an academic—even though he likes to footnote hisaddresses in scholarly fashion. His talks arepainstakingly prepared arguments, a fewpoints backed by conservative logic, and hemakes it clear that he expects further argument, pro and con. Freedman wantsDartmouth's future to be determined by"conversation" or genteel debate.

One of the best examples of the Freedmanstyle is the address he gave in late Octoberto the Dartmouth General Faculty. "Thescope of a formal address allows me the rareopportunity to examine in some detail thethemes that I hope we will be debating,modifying, and implementing in themonths immediately ahead," he told the assembled professors.

His speech contains the most specific description of Freedman's academic visionthat he has given at Dartmouth so far. Below is an adaptation of a large portion ofthat address.—Ed.

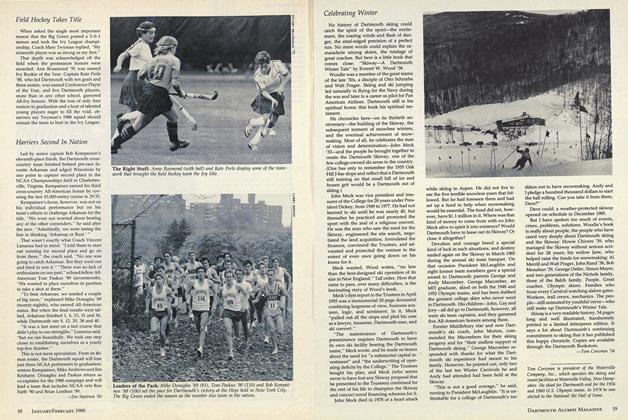

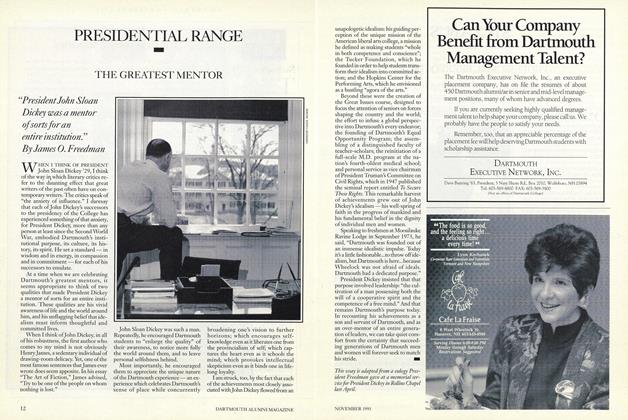

Drafting his arguments in his WebsterAvenue study, James O. Freedman makesa pitch for recruiting more women,minorities and foreign students whilebeefing up the international curriculum.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

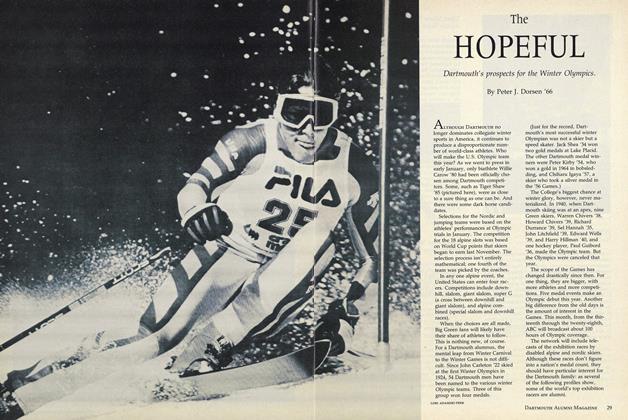

FeatureTHE HOPEFUL

February 1988 By Peter J. Dorsen '66 -

Feature

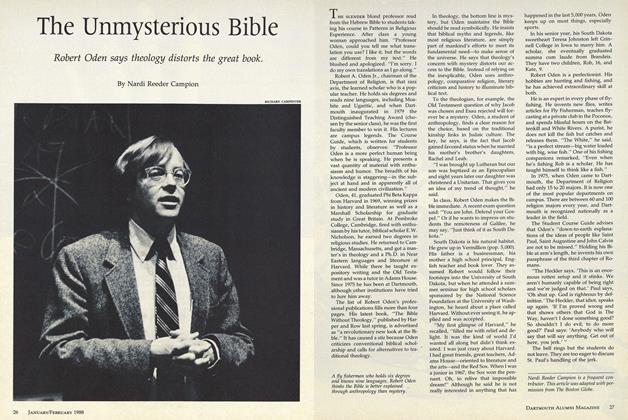

FeatureThe Unmysterious Bible

February 1988 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Sports

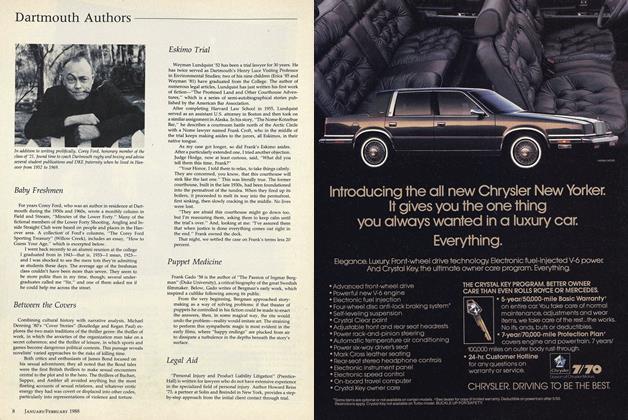

SportsCelebrating Winter

February 1988 By Tom Corcoran '54 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

February 1988 -

Article

ArticleFour Alumni Authors from the '40s to the '80s

February 1988 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Black Monday

February 1988

James O. Freedman

-

Article

ArticleMY HEROES

MARCH 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

FeatureHONEST TO GOD ACCOMMODATION

OCTOBER 1991 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleTHE GREATEST MENTOR

NOVEMBER 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleNothing Less Than a Hero

April 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Time Allotted Us

June 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleBack to the Future

JUNE 1998 By James O. Freedman

Features

-

Feature

Feature"Your Business Here..."

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Final Report

DECEMBER 1971 -

Feature

FeaturePiano Man

Sept/Oct 2004 By BONNIE BARBER -

Cover Story

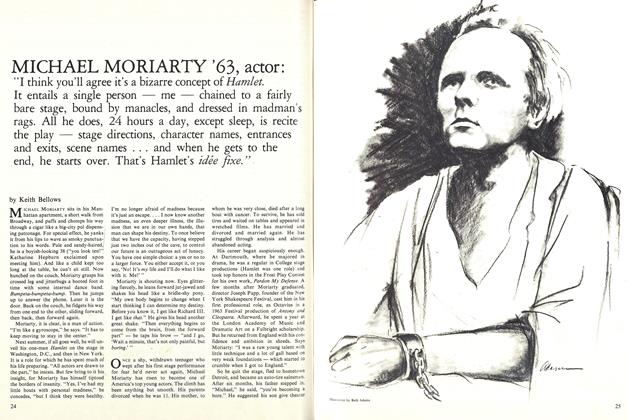

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

FeatureWhy I Traded Basketball for Biology

MARCH 1989 By Liz Walter '89 -

Feature

FeaturePoet of Place

December 1973 By R.B.G.