An alumnus offers an alternative to President Freed man's vision of a liberal-arts university.

"President Freedman did us all a favor when he brought the collegeuniversity issue out into the open," says Sandy Apgar, who began drafting his own views of Dartmouth's future immediately after reading the president's speech in the winter issue.

Apgar has been an active alumnus for more than a quarter century. After graduating from Dartmouth in 1962, he studied at Oxford and earned an M.B.A. at Harvard. He was instrumental in establishing the Class of 1962 Faculty Fellowship and has served as an officer of the Dartmouth Club of London. A director of Alex. Brown Realty Advisors, Inc., in Baltimore, he has also advised to the United Kingdom on educational management, taught at Harvard, and authored two books and more than 40 articles on management, real estate and public-policy issues. —Ed.

The college-or-university issue lies at the heart of Dartmouth's competitive position in American higher education. Its resolution will profoundly affect her stature, quality and resources for decades to come. Call it the second Dartmouth College Case: will she fulfill her destiny as the premier national institution in her class? Or will she be shackled by a vision that, while noble in spirit, is impractical to implement?

In his winter Alumni Magazine article, and in other public pronouncements, President James O. Freedman offers to clarify Dartmouth's mission and institutional character. He also leaves little room for doubt as to where he stands: he wants Dartmouth to be a university, to compete for students who aspire to Harvard or Stanford, and to attract faculty who pursue research at the "frontiers of knowledge." As an alumnus of Harvard and Yale, whose reputation was made at Pennsylvania and lowa,- his university perspective is understandable. The issue is whether the Dartmouth community shares these aims and goals, or prefers to see its unique collegiate culture sustained and enhanced.

Love of learning, breadth of understanding, skill in critical inquiry and pragmatic wisdom are what the College is about. In principle, of course, one may achieve the same in a university. But Dartmouth has fostered an environment of intellectual and social fellowship in which these attributes of leadership are probable—not merely possible. Daniel Webster's exhortation, "It is ... a small college, and yet there are those who love it," is not an empty platitude but a driving institutional force of shared values, as strong and relevant today as in 1819.

The challenge now is to farther strengthen Dartmouth's competitive position without eroding those values or diluting the undergraduate liberalarts focus. An axiom of competitive strategy is to seek niches in which to excel and to avoid head-on confrontation, with dominant powers. Think of Switzerland among nations, Nordstrom's in retailing, the Walters among art galleries. Dartmouth's strength is in providing exceptional undergraduate education in a vigorous yet intimate atmosphere and a natural environment of serene beauty. To compete directly with the Harvards of this world risks compromising the emphasis on undergraduates, dissipating both intellectual and financial resources, and weakening the very foundation that has made the College what she is today.

The president declares that Dartmouth is a "small liberal-arts university" in all but name. Among his various reasons, four favor university status: (1) attract and retain talented faculty who otherwise would be lost to the large research universities; (2) improve scholarship, especially by emphasizing new areas of knowledge that build on significant research, in order to enrich and diversify the intellectual environment for both faculty and students; (3) attract gifted undergraduates who judge colleges and universities by the "rigor and excitement" of the educational experience they offer; and (4) increase research support by placing Dartmouth in the mainstream of grants with a clear, research-oriented image.

Persuasive as they are, these arguments seem to be based on a self-folfilling proclamation: that the undergraduate liberal-arts college no longer can sustain a level of academic excellence and competitive superiority without the status of a full-fledgedalbeit small—university. They imply that the traditional mission to educate leaders of distinction and humanity has somehow been eclipsed in this era of specialization and technocracy. But where is proof of this premise? What are Dartmouth's "natural" attractions for these various constituents? Why does the administration perceive deficiencies in faculty and student quality when Dartmouth appears to be attracting people of extraordinary talent and dedication? Does the traditional mission to educate leaders compel the change to a research-oriented university? And do the benefits of this change outweigh the costs and potential risks?

Dartmouth does not have, and would be hard-pressed to develop, sufficient resources to feed a university-sized appetite. Harvard's endowment is more than seven times ours; Princeton's is more than four. We do not have an equivalent pool of wealthy individual and major corporate donors. Development of a sponsored research fund for graduate programs is a daunting, expensive and highly competitive task; Johns Hopkins had 15 times the level of Dartmouth's research grants in 1988. In short, our resources are finite; generous for an undergraduate college and probably sufficient to achieve supremacy, but limited for a university and insufficient for the top rank.

In addition, a research orientation is likely, over time, to erode Dartmouth's historic strength as a liberalarts college. Dartmouth produces leaders because she educates generalists (and the American economy sorely needs more of them). But as their rewards are skewed toward institutional research, teachers are forced to specialize. While the president has highlighted the need for intellectual cross-fertilization and interdisciplinary programs, the faculty as individuals should be sparking the connections—the synthesis—that the generalist learns to make.

How can Dartmouth fulfill its traditional mission while meeting the competitive challenge?

First, stress undergraduate teaching in an environment of intellectual rigor, tolerance and excitement.

Teaching excellence should be the prevailing value of the community of scholars—both for faculty and for students—and the dominant criterion in both recruiting faculty and awarding tenure. Research should be clearly positioned as a means to nourish teacher-scholars and to stimulate the process of collegiate learning, not as an end in itself.

I was privileged to attend Oxford as a graduate student. One of the world's distinguished universities, Oxford nonetheless places primary emphasis on undergraduate teaching within its relatively autonomous colleges. Save for the sciences, research remains largely an individual, independent quest—not a series of institutional programs. The Oxford tutorial is a decidedly rigorous intellectual experience, infused by brilliant teachers in the Socratic tradition, not by Ph.D. programs and graduate assistants. Dartmouth still enjoys the same emphasis on teaching and must guard it from infringement.

Second, focus current and solicited funds on teaching.

The new Presidential Scholars program is an outstanding initiative to signal Dartmouth's emphasis on intellectual distinction among students. Similar incentives should be explored for faculty. Interdisciplinary courses should receive disproportionate funding to spawn new areas of knowledge in the core curriculum, but other programs should be scrutinized for their relevance and contribution to the undergraduate teaching mission. Support to faculty should reflect practical needs that will be as important as research to the teaching mission—for example, travel grants for academic conferences to enhance Dartmouth's presence as well as the individual's; and subsidies for housing in Hanover's prohibitively expensive market.

Third, strengthen the three existing graduate schools, both as independent units and in interdepartmental programs.

It is significant that Tuck, Thayer and the Medical School are professional, not academic, in character. Consistent with the College's mission, they also produce leaders. Last winter's Business Week survey, "The Best B-Schools," lauded Tuck for its quality and accorded it third place. Among the top 25, Tuck is notable for not having a doctoral program.

Because the graduate schools have achieved national distinction, and also have the potential for programmatic innovation, they deserve additional support to achieve their aims. Each in its own way can be financially selfsupporting in research without diverting resources from undergraduate teaching. Moreover, there can be valuable spillover to undergraduate programs; for example, closer links already have been forged between the Medical School and undergraduate science departments, while Tuck has much to contribute to the Economics Department.

Fourth, limit other graduate programs to areas of demonstrable competitive strength and importance.

It makes sense for small groups of graduate programs to support the nationally recognized mathematics, computer science and music departments; but 12 doctoral programs, two master's programs and other specialpurpose programs seem excessive for a rural undergraduate college. The academic equivalent of zero-based budgeting would serve well here: does Dartmouth need to be in the vanguard of Caribbean studies and molecular genetics to stimulate the searching mind of a 20-year-old? If a few graduate programs are deemed to be essential to the mission, the humanities most deserve consideration for new investment for their low cost and high impact on the core liberal-arts curriculum.

Fifth, forge alliances with specialpurpose research institutions to complement the College's strengths and diversify its curriculum without high overhead.

During my senior year, I spent a term at MIT with the distinguished political scientist Robert Wood, in the Joint Program in Urban Studies, and returned to Hanover on the weekends. While I never would have considered attending MIT as an alternative to Dartmouth, this arrangement greatly enlarged my horizons, leveraging my course work and Dartmouth's small, specialized faculty. It will take initiative and creativity to organize joint ventures, partnerships and other forms of cooperative academic enterprise such as this, but the payoff will come in a broader array of programs with scholars of distinction than the College could afford or attract on its own.

The move toward university status has been an incremental, creeping decision, not the result of broad consensus on a deliberate strategy. President Freedman is to be admired for his boldness in getting the issue out into the open. Faculty, alumni and students are all stakeholders in the Dartmouth enterprise and should be polled on this issue.

In doing so, let us consider anew the heritage that Webster, Thayer, Hopkins and others have reinforced and defended for more than two centuries. Leadership qualities, and intellectual excellence, do not depend on a university structure or institutionalized research; they are brewed in the crucible of humanistic values, spirit and environment that are unique to this college and may not flourish if the structure is changed. In short, Dartmouth's mission should make clear that she is today, and aspires to be in the future, a great liberal-arts college of international renown rather than a small liberal-arts university of uncertain stature.

Dartmouth should be to academia as Switzerland is to the world, says Apgar.

"Daniel Webster'sexhortation is not anempty platitude but adriving institutionalforce of sharedvalues."

"An axiom ofcompetitive strategy isto seek niches in whichto excel and toavoid head-onconfrontation withdominant powers."

"Dartmouth does nothave, and would behard-pressed todevelop, sufficientresources to feeda university-sizedappetite."

"The move towarduniversity status hasbeen an incremental,creeping decision, not the result of broadconsensus on adeliberate strategy."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhen Dialogue Turns to Diatribe

May 1989 By Larry Martz '54 -

Feature

FeatureLet's Start a Genuine Discussion About Our College

May 1989 By George Munroe '43 -

Feature

FeatureStudents in a "Goldfish Bowl" Rise to Debate

May 1989 By Ron Lepinskas '89 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCAN WE TALK?

May 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleREVIEW LOSES SUIT

May 1989 -

Article

ArticleSTARSTRUCK

May 1989 By Gary Wegner

Mahlon Apgar IV '62

Features

-

Cover Story

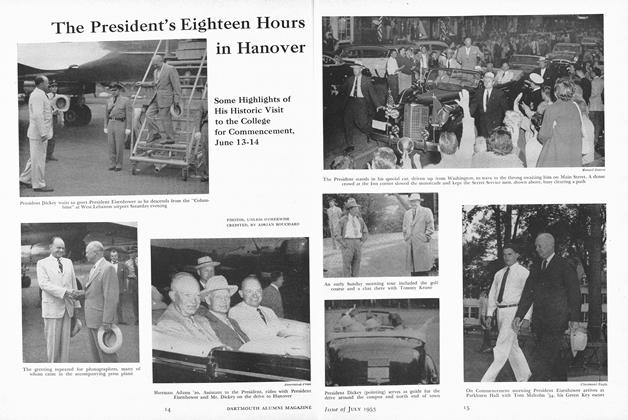

Cover StoryThe President's Eighteen Hours in Hanover

July 1953 By ADRIAN BOUCHARD -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYWhy Is Dartmouth So Expensive?

MAY | JUNE By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

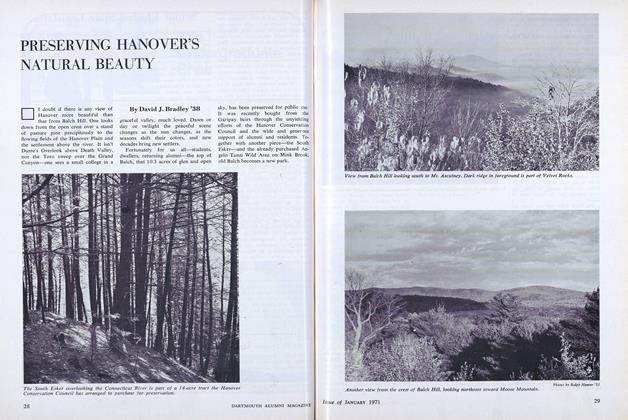

FeaturePRESERVING HANOVER'S NATURAL BEAUTY

JANUARY 1971 By David J. Bradley '38 -

FEATURE

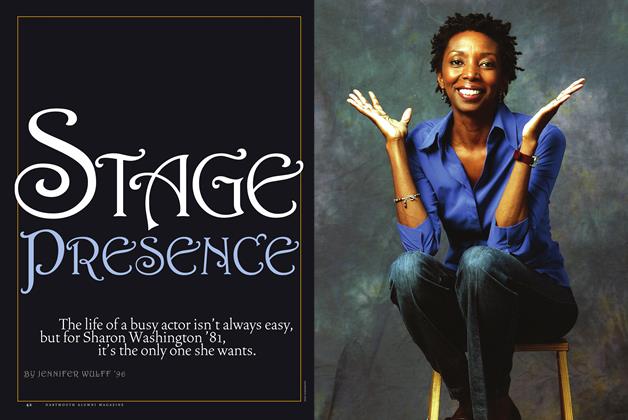

FEATUREStage Presence

Mar/Apr 2009 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

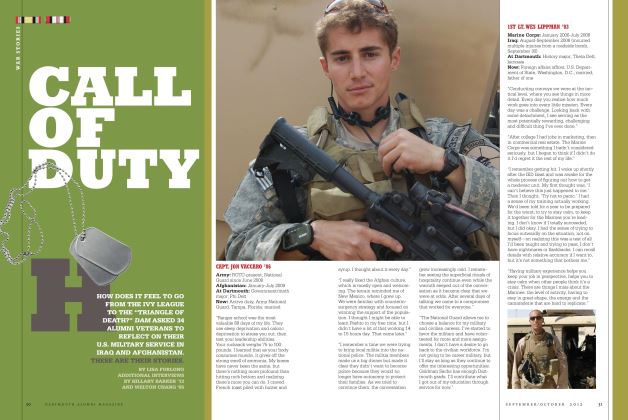

FeatureCall of Duty

Sep - Oct By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureThe Uncompetitive Society

MAY • 1987 By Richard D. Lamm