Jerome Brody '44 uses both to cut a spectacular swath through the New York restaurant field

FOR Manhattan's hurried, harried, moneyed inhabitants it takes more than the plain unusual to win a second glance, and even the spectacular often fails to penetrate their blasé shells. This is especially true in the restaurant field, where block after block of satisfactory, often quite notable, establishments compete for customers by offering elegance or novelty as well as good food. But one man, a native of the big city, lately has given New Yorkers and the restaurant world something to talk about - and he is likely to keep them talking.

He is Ira Jerome Brody '44, president of Restaurant Associates, Inc., a group of aggressive and imaginative young men currently engaged in managing a varied string of restaurants that in effect cater to New York clear across the board. The latest and brightest jewel in their corporate crown - and the cause of most of the talking — is The Four Seasons, a four-and-a-half-million-dollar combination of art and gastronomy in the newly opened Seagram Building. Prior to this addition in July, a lot of interest was focused, and still is, on another sophisticated creation of theirs called The Forum of the Twelve Caesars, located in Rockefeller Center. Both of these extraordinary restaurants bring joy to the epicure, though the joy might come dearly; Restaurant Associates has an interest in making sure it is all a good investment. But the New Yorkers and visitors catered to by such restaurants are not exactly famous for their economic restraint.

The operations of Restaurant Associates began quite modestly some years ago with the low-priced Riker cafeteria chain - "No Better Food at Any Price" - and then gradually expanded into the present high-rent district. Along the way from Rikers to Park Avenue, Brody and associates gathered in the experience of a number of other operations, all noteworthy in their own right: the Newark Airport Restaurant, Leone's, the Hawaiian Room of the Lexington Hotel, and the Brasserie, located just around the corner from The Four Seasons. And there is more to come; to be opened soon in the new Time-Life Building is the Fonda del Sol, featuring Latin-American atmosphere and cuisine.

Despite the impressive breadth and quality of this list, it has taken a spectacular and costly enterprise like The Four Seasons to make Brody's accomplishments known to the public as they have long been known in the restaurant field. This new and talked-about restaurant, on the first floor of the Seagram Building, occupies a series of rooms raised slightly above street level and overlooking Park Avenue. Architect Philip Johnson and interior designer William Pahlmann, with assists from Mies van der Rohe, Saarinen and Eames, have achieved a stunning effect, and spared no expense in doing so.

Once inside it is soon discovered that the name is not without significance, for the seasonal characteristics outdoors are subtly reflected by the stately decor within. Sometime around the recent autumnal equinox, summer trappings disappeared overnight to make way for new wall hangings and, in honor of the fall months, whole potted trees, their foliage bathed with russet and orange late-season coloration. Rippling metallic chains flow across the high windows with mesmerizing regularity and a floating design of long brass rods by sculptor Richard Lippold hangs gracefully from the ceiling, diffusing the whole place with the sunny warmth of an October afternoon. Art treasures by Miro, Picasso, and Pollock, their overall value approaching a quarter of a million dollars, adorn passageways and reception rooms, giving a sense of life and beauty to The Four Seasons that contrasts sharply with the antiseptic austerity of the Seagram Building's exterior.

Glancing over the menu, it is again evident that seasonal variations are reflected; however after awhile one tends to suspect that in many cases it is principally the same fare with a new press agent. Still, it is a rich and impressive list, living up to the highest expectations, and it would be difficult to come away from the table without the serene smile of a contented gourmet.

The service, needless to say, is perfection itself, that ultimate state in which it is everywhere at once yet so discreet as to be practically unnoticed. There seems to be little attempt at regal elegance or flourish as might be found at such places as the Plaza, but the waiters make up an invisible backdrop always available when needed and amazingly courteous and afforms, colorful but simple, also change with the seasons; and the restaurant's trademafk, a small band picturing a quartet of trees as they might appear at different times of year, is worn on the tunics like a military decoration.

Distinguishable noises are notable only by their absence and the audible background is a ripple of conversation blending perhaps with the sizzling of brandy over a crepe suzette or the bubbling of a pool. This particular pool, by the way, is in the center of the north wing of The Four Seasons and it can be completely covered for dancing or partially covered with runways for the fashion shows that frequently take place there. One publicity agent suggested jokingly that a model could get her name into print by simply falling into the uncovered part of the pool some day, but that is the sort of thing you just wouldn't think of doing at The Four Seasons.

As you leave The Four Seasons and walk down the Avenue a bit, and then turn west across town for two blocks, Rockefeller Center looms up in all of its magnificence. On the first floor of the Center's Goodyear Rubber Building is another of Brody's blue-chip offerings, The Forum of the Twelve Caesars, smaller and less august than The Four Seasons, but unique in its own way and dedicated to Lucullan pleasures in the elegance of an empire. As the guest picks up the menu he is met by the dictum, Cenabis Bene ... Apud Me, an invitation to the feast. The impression one begins to receive is that this would be sort of a university club for the Roman emperors were they alive today. Grace and authenticity are stressed at The Forum, with busts and portraits of the first twelve Caesars around the walls adding to the imperial flavor. The staff has been well indoctrinated with a background of Suetonius, and the chairman of the classics department of Hunter College checked the décor and menu Latin for correctness.

The fare of Universal Rome was the fare of Europe, Africa, and nearer Asia, giving The Forum a wide leeway in its spread. Over thirty per cent of the menu is prepared in the manner described by Apicius, compiler of the Roman cookbook, the first known to western civilization. The unusual is common, with such suggestions as wild boar from the lands of the Belgae, salmon baked in ashes, roasted peacock, and many more, all creating infinite possibilities for imperial delights.

Leaving The Forum one could take a cab, or if it's a nice day walk, over to Leone's on 48th Street; and then there's always the Hawaiian Room in the Lexington Hotel, or for a late snack how about the new Brasserie? Try any of them and you will still be in the domain of Jerry Brody's Restaurant Associates; and strangely enough it all came about almost by chance.

THE country was at war when Jerry Brody was at Dartmouth; and he left for Air Force pilot training in February 1943, without being able to graduate with his class. He had gotten started in Tuck School and risen to be business manager of The Dartmouth, knowing that he wanted to be a businessman in later life but with no more specific plans than that. When hostilities ended and he was discharged from the Air Force, he joined his father's New York hat company.

In 1942 he had married a Smith girl, the former Grace Wechsler of New York, whose family was connected with the original Restaurant Associates, operating at that time only the Riker chain of cafeterias. By the end of the war the old family management was dying out and Rikers had come upon lean days, but it was at this fateful moment that Brody's father-in-law prevailed upon him to take over Restaurant Associates and try to nurse it back to health. He knew nothing about the restaurant business and the first two years were rough going, but the line was held and things began to look up. Improvements he made produced gratifying results, but progress was painfully slow because there was not enough capital to renovate die facilities and pull Rikers up by its bootstraps. Expansion, it was obvious, would have to go in other directions.

It was a moment of decision and at this juncture an opportunity presented itself. The terminal buildings at the Newark Airport were nearing completion and the airport officials were looking for someone to handle the restaurant concession. Restaurant Associates threw their hat in the ring and were given the contract. But at this point they went out on a limb; rather than the mediocre eating facilities commonly designed for airport transients, they plunged in and created a first-class community restaurant, hoping against hope that it might catch on. It did, and with a real flourish. Brody and his associates had correctly sensed the local feeling of inferiority concerning restaurant facilities prevalent in northern New Jersey. The residents immediately adopted the excellent Newark Airport Restaurant as their own and when Manhattan friends would suggest meeting them for dinner someplace in New York, they could now counter with, "Why don't you come over and try our place."

This first outside project had been a happy one and Restaurant Associates now began to gain the experience necessary to launch into more sophisticated ventures. When the next opportunity presented itself they were ready. New management was taking over the Lexington Hotel, and the Hawaiian Room, which had been consistently losing money for the hotel, was about to be closed. Brody asked to have one last shot at making the Room pay its own way and was given it. Efficient management policies were set up and legitimate Hawaiian food and atmosphere introduced. Business was soon doubled, the operation was out of the red, and another new success had been added. Other concessions came along soon and Restaurant Associates established a reputation as men who could handle the job.

Brody feels that since the firm even today is essentially under-capitalized, it is still their reputation and skills they are selling. He came in as an amateur and admits that in many respects he still is one, never having had the time to gain basic restaurant experience or strike up a rapport with the old professionals. But possibly as a result, his ventures have been noted for their original approach and fresh personal touch. He finds it a challenging and cosmopolitan field, unique in its opportunities every day to meet new and interesting people. Yet it never ceases to be a gamble. He hasn't had a lame opening yet, but the public can never really be predicted. It's a lot like show business, he says. "You just open the doors the first night and pray that someone will come in." His prayers so far have been answered profusely.

Restaurant Associates has a small building of its own on West 57th Street housing administrative offices and a commissariat. To the casual observer just peeking in it appears to be just like any other large business operation complete with scurrying well-dressed secretaries, personnel men tied up in union contract negotiations, and harassed public relations staffers. Brody himself supervises the operation like a general with a competent and trusted staff, registering final approval or disapproval on the preparations of others. His personal attention is mostly focused upon negotiations for new concessions or, as he says, "sitting up with the sickest child."

Due to recent successes and obvious managerial talents, the group has been expanding at an accelerating rate with really no end in sight. Though they have found by far the most favorable results in the high-quality, high-priced restaurant field, there is no particular pattern to this expansion and they more or less play it by ear, following whatever paths economics or current opportunity tends to open to them.

Aside from the business end, Brody finds some of his greatest satisfaction in the creative aspects of each new operation. The necessity of personally planning and checking on an infinite number of details brings him into contact almost every day with talented and fascinating people. It's exciting and one of the wonderful breaks of the job, he claims. He knows full well that he is constantly being brainwashed by the designers and artists, but he still enjoys it and modestly insists that he has a lot to learn. Recently when the question arose as to whether a certain section of The Four Seasons was to be decorated with a Picasso or the work of an American artist, Brody felt that only native artists should be represented on the walls. However the experts and professionals worked on him for awhile and that night he thought it over. It didn't take long - and Picasso prevailed.

The Brodys and their three children live in Scarsdale. For recreation the family has a boat on Long Island Sound. It's a 34-foot sloop and Brody claims that, just as with his restaurants, he plunged in and bought it, then started learning how to handle the darned thing.

It was almost chance that landed him in the restaurant business twelve years ago instead of in some more prosaic profession. Is he still happy about it? Sure, he says, "It's been a lot of fun."

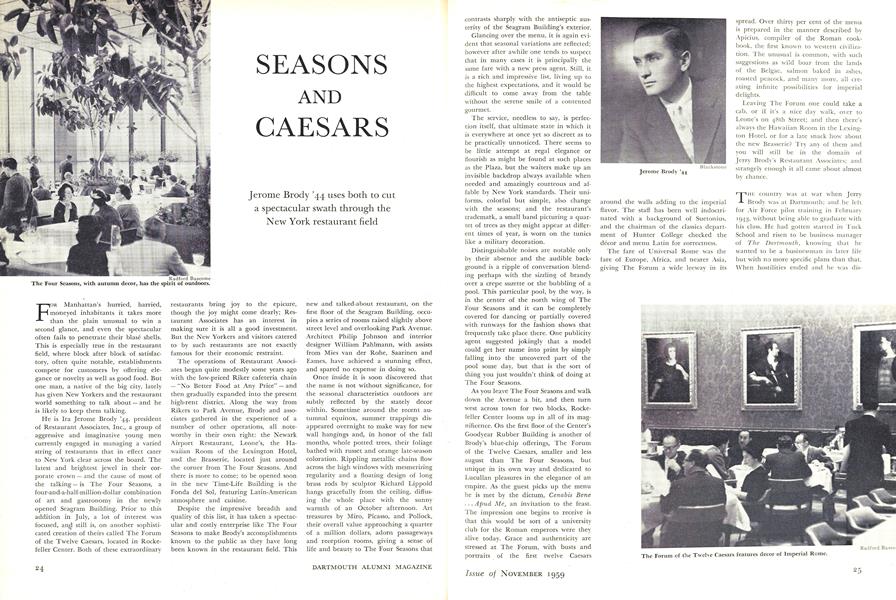

The Four Seasons, with autumn decor, has the spirit of outdoors.

Jerome Brody '44

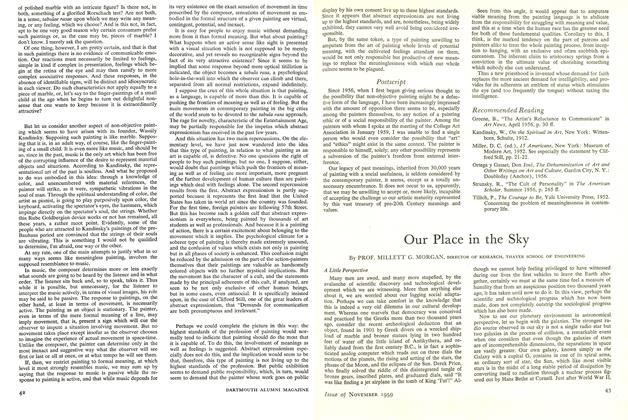

A floating design of brass rods by sculptor Richard Lippold is one of the modern art treasures adding to The Four Seasons' fame.

Some Roman touches at The Forum's bar.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOur Place in the Sky

November 1959 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN, -

Feature

FeatureCan Chinese Civilization Survive Communism?

November 1959 By WING-TSIT CHAN -

Feature

FeatureSocial Responsibility in Painting

November 1959 By CHARLES T. MOREY, -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Fellowship

November 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth and Saint Francis

November 1959 By GORDON M. DAY -

Article

ArticleHow I Conquered Alcohol

November 1959 By ALAN COOKE '55

JIM FISHER '54

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWHEELOCK’S FULFILLING OF THE SCRIPTURE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureFive Plays for All Seasons

September 1975 By DREW TALLMAN and JACK DeGANGE -

Feature

FeatureKappa Kappa Grandpa

MAY 1985 By Gabrielle Guise '85 -

Feature

FeatureWatergate and the Press

December 1973 By H. WILLIAM SHURE -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Section 504

DECEMBER • 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

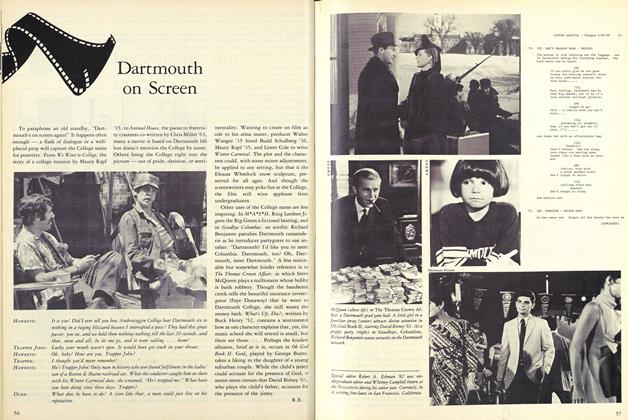

FeatureDartmouth on Screen

November 1982 By R.E.