Philosophers unveil the logic of nuclear deterrence.

Many students who take my course on the ethics of nuclear deter rence think they can just announce what they believe. Discussions intensify when the students face classmates and authors who support conflicting positions on the arms race. This is where philosophy comes in. My goal is to help students formulate the moral principles underlying their own positions and to understand and respect the arguments of their opponents.

Since most Americans support nu-clear deterrence, the most stimulating arguments come from those who oppose it. Such challenges might seem less important now that U.S.-Soviet relations are improving, but actually some of the reasons to abandon nu-clear deterrence are just as strong and perhaps stronger—if we do not need to fend off an evil empire. There are two main arguments against nu-clear deterrence: one emphasizes the intentions of the policy; the other deals with its consequences.

Most people who find nuclear deterrence morally questionable focus on the intentions behind it. The American Catholic Bishops and Reagan, in his "Star Wars"speech, focus on intentions. A simple and extreme version of this argument runs as follows. Nuclear deterrence requires an intention to retaliate after a large nuclear attack. But it would be morally wrong to use nuclear weapons to retaliate. The "wrongful intentions" principle tells us that it is morally wrong to intend to do what it is morally wrong to do. Therefore, nuclear deterrence must be morally wrong.

I find few students who want to accept this conclusion, but it cannot be avoided without denying one of the premises. Some defenders of nuclear deterrence deny the wrongful intentions principle, but they need to explain why it is morally wrong to intend to murder someone even if you fail to carry it out, why we never call reflex movements or accidents immoral when they are unintentional, and, more generally, why intentions seem so important to morality. Some students deny that it would be wrong to retaliate after a large nuclear attack, but they need to explain why it is permissible to kill millions of innocent people, especially if there is little left to defend after the nuclear missiles go off. Finally, some students deny that deterrence involves any intention to retaliate, but they need to explain how bluffing is possible in our open society. Since each response has problems, many students find that they have to question their basic assumptions if they still want to defend nuclear deterrence.

The second main argument against nuclear deterrence focuses on the consequences of various policies. Despite the ambiguous slogan "Better dead than red," most students think that all-out nuclear war is worse for most people in the world than Soviet domination. This speaks against nu-clear deterrence because two-sided nuclear war would not be possible if we gave up nuclear deterrence. The usual response is that the probability of all-out nuclear war under deterrence is very low, but nuclear disarmament would create a much greater risk of Soviet domination. If so, we have to choose between a lesser risk of a greater harm and a greater risk of a lesser harm. Opponents of nuclear deterrence then argue that nuclear disarmament would probably not lead to Soviet domination, since the Soviets are basically paranoid instead of expansionist. They also argue that the harms of nuclear war to future generations—especially given nuclear winter—are much greater than the harm of Soviet domination for some temporary period, as there are many times more people yet to be born than are now alive.

These arguments obviously rely on assumptions about what the consequences of various policies will be, but we cannot be sure that these assumptions are true. Since we do not know the absolute magnitudes or probabilities of the harms involved, we have to develop some way to decide under conditions of uncertainty. Considering only the worst-case and the bestcase scenarios overlooks the crucial question of how likely each scenario is. What we need is a principle that uses the information that we have within the limits of the uncertainties that we cannot escape. Philosophers have suggested such principles for similar moral problems, but all are controversial. In the end, we all have to determine our basic attitude toward risks and uncertainties.

Now we can turn to arguments for nuclear deterrence. Many people argue that nuclear deterrence produces the best consequences—peace—but these arguments run into the same uncertainties as above. The other main argument for nuclear deterrence employs some principle of self-defense. Killing is usually wrong, but the most commonly accepted exception is self defense. However, not all self-defense is justified. I am not permitted to kill an attacker if I can stop him just as well by knocking him down without killing him. Most people also think that it would be wrong for me to kill an innocent bystander in order to prevent someone else from killing me. The issue is whether nuclear deterrence is like those cases where self-defense is not justified. If Soviet citizens are innocent bystanders, or if we could prevent Soviet aggression without using nuclear weapons, then nuclear self-defense might not be justified. These limitations on self-defense raise questions about whether it is permisible to target cities and about whether particular weapons—the 82, MX, INF, SDI—really are necessary for self-defense. Here we have to distinguish many kinds of nuclear deterrence, since some might be necessary and justified even if others are not.

Most students eventually ask whether there is any solution to the problem of nuclear deterrence. At this point, I usually introduce some material from my own book, Moral Dilemmas. I argue that some moral problems have no solution, because each incompatible alternative is somewhat wrong and neither alternative is objectively more wrong. If nuclear deterrence fits this pattern, then reasonable people can disagree. By recognizing this possibility, we can learn to respect other people's views in such moral dilemmas, even when we still disagree with them strongly. For farther reading, see the books below.

Walter Sinnott-Armstrong teachesstudents to explode arguments.

When he got a "D" in the introductory philosophy course he took as an undergraduate at Amherst College, Walter Sinnott-Armstrong. was more challenged than chagrined, "I figured that the professor could teach me something," he recalls. Now a professor of philosophy himself, Sinnott-Armstrong tries to help his students look behind their assumptions about the World by learning how to analyze arguments and positions systematically, he teaches his students to apply philosophy all issues in life—"from the tragic to the trivial," as he puts it.

As a high school student at Hotchkiss, Sinnott-Armstrong had aimed toward a career in engineering until a philosophy-heavy religion course stole his interest. He never fully abandoned science, however; rather, he shifted points of view. "Does science give us knowledge of the world?" he asks as a philosopher, providing his own answer: "There are certain things we can know, but the interesting things are the theoretical. For example, is there such a thing as a black hole? We can't see it or go to it. Can we know it?"

Theory of knowledge—episteinology—is one of Sinnott-Armstrong's primary interests in philosophy. The other is ethics. He has already published a book ethical theory (see "Props 0Choice") and is now in the thick of a new hook about moral knowledge.the book will deal with such theoretical giants as: "Can moral propositions and "What is truth?"

Sinnott-Armstrong combines his scientific and philosophical bents to deal with what he calls "the most important issue we face": nuclear war. But assessing the arguments for and against nuclear deterrence isn't just philosophers' play. "Ethical argumentation can affect public policy," claims the professor. He notes that Jimmy Carter's readings of philosophy led him to conclude that aiming nuclear weapons at cities—rather than at weapons—is wrong. Reagan, according to Sinnott-Armstrong, used the argument against nuclear deterrence as a justification for "Star Wars." The professor says that while students who take his course on nuclear deterrence rarely their opinions, they "argue better, refine their views, understand their opponents. They get away from sloganism and name-calling. And they often find out that they and their opponents are not so far apart."

Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

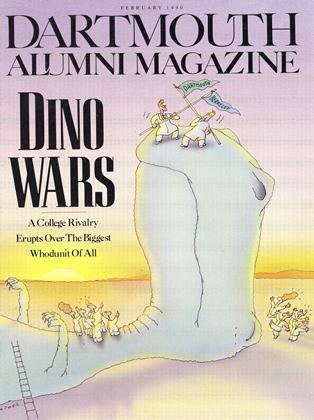

Cover StoryDino Wars

February 1990 By Roving Writer Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

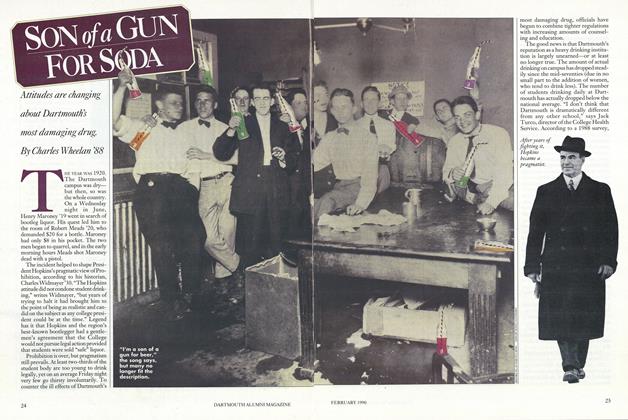

FeatureSon of a Gun for soda

February 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureIf You Thought the Comps Were Hard, Try This Quiz

February 1990 By Nancy Staab '90 -

Feature

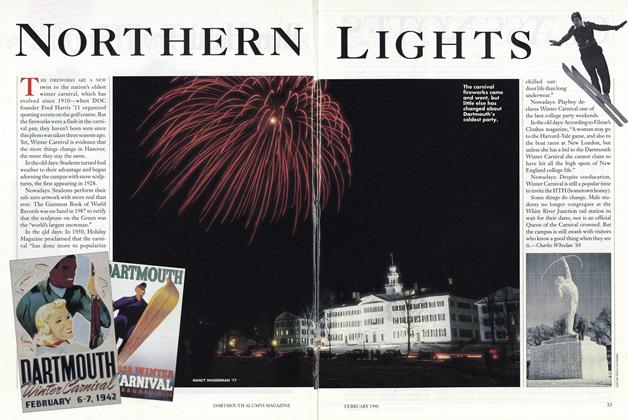

FeatureNorthern Lights

February 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

February 1990 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

February 1990 By W. Blake Winchell