How astudent playedan extremelyminor role inthe creation ofDartmouth'smostcontroversialpiece of art.

THE STORY GOES THAT WHEN Ernest Martin Hopkins '01 turned over the presidency of Dartmouth to John Dickey '29 he said, "I'm going to give you only one piece of advice, John: Don't commission any murals."

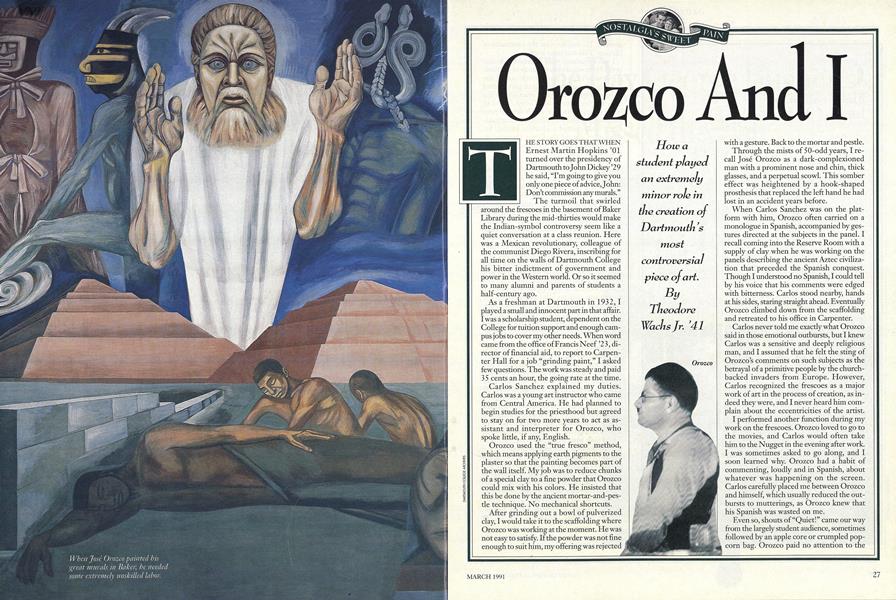

The turmoil that swirled around the frescoes in the basement of Baker Library during the mid-thirties would make the Indian-symbol controversy seem like a quiet conversation at a class reunion. Here was a Mexican revolutionary, colleague of the communist Diego Rivera, inscribing for all time on the walls of Dartmouth College his bitter indictment of government and power in the Western world. Or so it seemed to many alumni and parents of students a half-century ago.

As a freshman at Dartmouth in 1932, I played a small and innocent part in that affair. I was a scholarship student, dependent on the College for tuition support and enough campus jobs to cover my other needs. When word came from the office of Francis Neef '23, director of financial aid, to report to Carpenter Hall for a job "grinding paint," I asked few questions. The work was steady and paid 3 5 cents an hour, the going rate at the time.

Carlos Sanchez explained my duties. Carlos was a young art instructor who came from Central America. He had planned to begin studies for the priesthood but agreed to stay on for two more years to act as assistant and interpreter for Orozco, who spoke little, if any, English.

Orozco used the "true fresco" method, which means applying earth pigments to the plaster so that the painting becomes part of the wall itself. My job was to reduce chunks of a special clay to a fine powder that Orozco could mix with his colors. He insisted that this be done by the ancient mortar and pestle technique. No mechanical shortcuts.

After grinding out a bowl of pulverized clay, I would take it to the scaffolding where Orozco was working at the moment. He was not easy to satisfy. If the powder was not fine enough to suit him, my offering was rejected with a gesture. Back to the mortar and pestle.

Through the mists of 50-odd years, I recall Jose Orozco as a dark-complexioned man with a prominent nose and chin, thick glasses, and a perpetual scowl. This somber effect was heightened by a hook-shaped prosthesis that replaced the left hand he had lost in an accident years before.

When Carlos Sanchez was on the platform with him, Orozco often carried on a monologue in Spanish, accompanied by gestures directed at the subjects in the panel. I recall coming into the Reserve Room with a supply of clay when he was working on the panels describing the ancient Aztec civilization that preceded the Spanish conquest. Though I understood no Spanish, I could tell by his voice that his comments were edged with bitterness. Carlos stood nearby, hands at his sides, staring straight ahead. Eventually Orozco climbed down from the scaffolding and retreated to his office in Carpenter.

Carlos never told me exactly what Orozco said in those emotional outbursts, but I knew Carlos was a sensitive and deeply religious man, and I assumed that he felt the sting of Orozco's comments on such subjects as the betrayal of a primitive people by the church-backed invaders from Europe. However, Carlos recognized the frescoes as a major work of art in the process of creation, as indeed they were, and I never heard him complain about the eccentricities of the artist.

I performed another function during my work on the frescoes. Orozco loved to go to the movies, and Carlos would often take him to the Nugget in the evening after work. I was sometimes asked to go along, and I soon learned why. Orozco had a habit of commenting, loudly and in Spanish, about whatever was happening on the screen. Carlos carefully placed me between Orozco and himself, which usually reduced the outbursts to mutterings, as Orozco knew that his Spanish was wasted on me.

Even so, shouts of "Quiet!" came our way from the largely student audience, sometimes followed by an apple core or crumpled popcorn bag. Orozco paid no attention to the protests. He had been on the barricades in Mexico. This was tame stuff.

I was never sure what interested Orozco in the Hollywood extravaganzas of the time. He couldn't have made much out of the English dialogue, but the visual part seemed to be enough to trigger a reaction. In the early thirties, movies were often filmed in lavish settings with expensively dressed people getting in and out of Stutz Bearcat roadsters. This created a pleasant fantasy for most of us during the Great Depression, but perhaps it only stirred Orozco's revolutionary instincts.

I wasn't around for the later stages of the frescoes. During my sophomore year the Depression closed in on my family and I had to leave Dartmouth for a while despite the help I was getting from the College.I worked for five years, then returned in 1939 and finished with the class of '41, thereby setting a record for undergraduate longevity that probably lasted until the GIs came back from World War II.

By the time I was again settled in Hanover, the frescoes were completed and Orozco was home in Mexico. Students read at the long tables in the Reserve Room or dozed in their chairs. Occasional tourist groups came through to gaze at the panels in awe and pass on. The controversy had faded away for the most part, as controversies generally do, and Orozco's "Epic of American Civilization" had taken its place among the important murals of the twentieth century.

While I won't quarrel with this judgment, the murals will always hold a different meaning for me. Whenever I hear or read a reference to them I will think of an 18 year old freshman watching a fierce-looking man pour out his soul in an explosion of color on the bare walls of Baker. Several years ago, I mentioned this limited viewpoint to Richard Teitz, then director of the Hood Museum, who was collecting material on Orozco. His reply was comforting. He said that the same might have been true when Michaelangelo did the murals in the Sistine Chapel.

I have sometimes thought about those nameless people who pounded clay for Michelangelo 500 years ago. I wondered if they ever got together over a bottle of chianti and talked about the strange fellow who lay on his back on a platform and painted pictures of the Creation on the Vatican ceiling. Hail, brothers!

When Jose Orozco painted his great murals in Baker, he needed some extremely unskilled labor:

Orozco

Old Mother! Motker off in the hills, by the banks of the beautiful river! - Richard Hovey

Theodore Wachs did a stint with the FBI andworked as a writer and editor until his death lastsummer in his hometown of Chicago.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMiraculously Builded In Our Hearts

March 1991 By Judson D. Hale '55 -

Feature

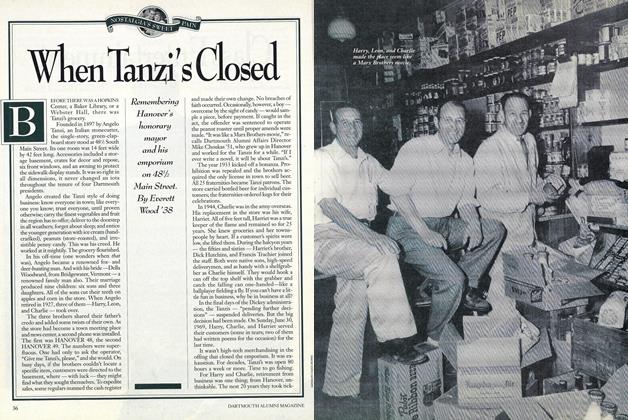

FeatureWhen Tanzi's Closed

March 1991 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

FeatureAn Unofficial (And, For That Matter, Not Altogether Pertinent) History of Dartmouth

March 1991 -

Feature

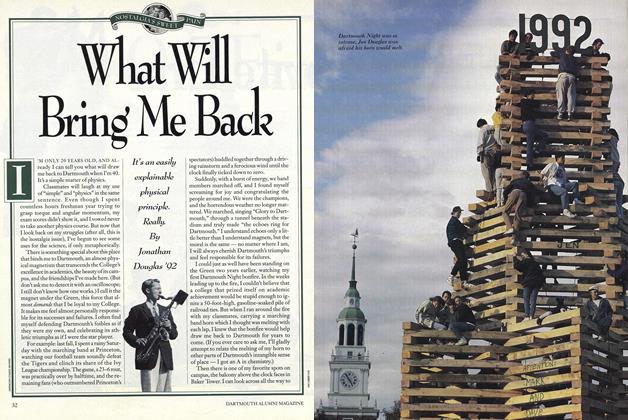

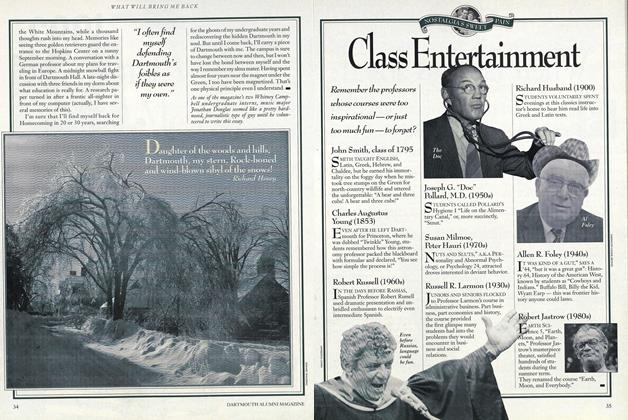

FeatureWhat Will Bring Me Back

March 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92, Richard Hovey -

Feature

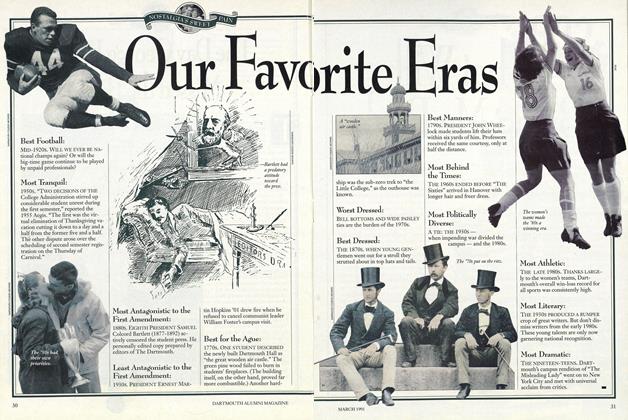

FeatureOur Favorite Eras

March 1991 -

Feature

FeatureClass Entertainment

March 1991

Theodore Wachs Jr. '41

Features

-

Cover Story

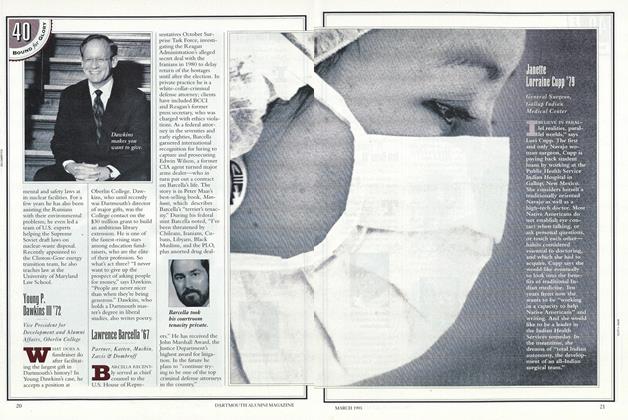

Cover StoryYoung P. Dawkins III '72

March 1993 -

Feature

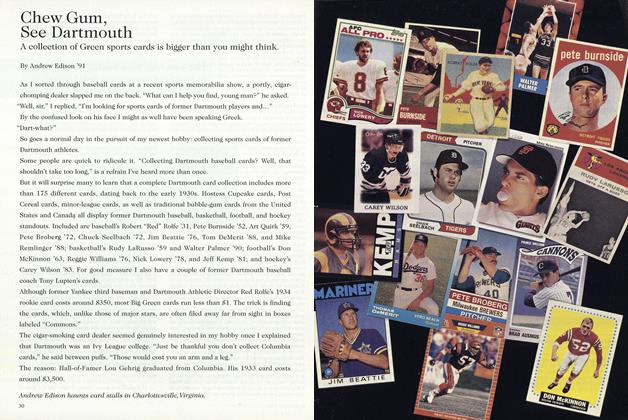

FeatureChew Gum, See Dartmouth

NOVEMBER 1993 By Andrew Edison '91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChris Miller '97

OCTOBER 1997 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

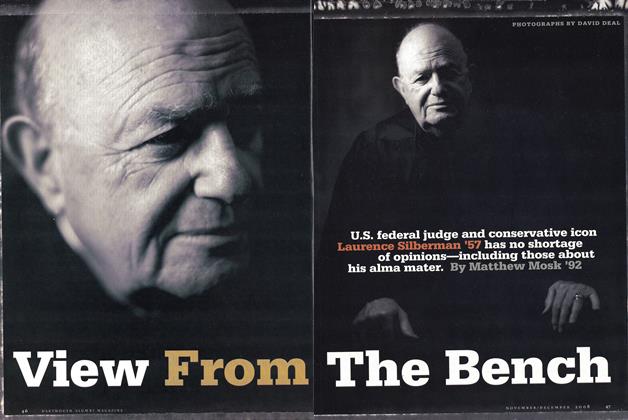

COVER STORY

COVER STORYView From the Bench

Nov/Dec 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

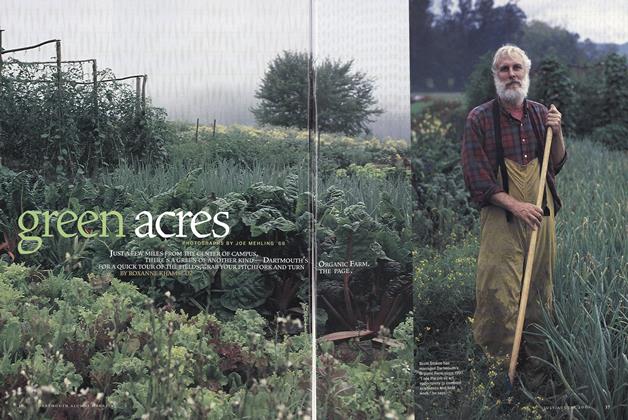

FeatureGreen Acres

July/August 2001 By ROXANNE KHAMST ’02 -

Feature

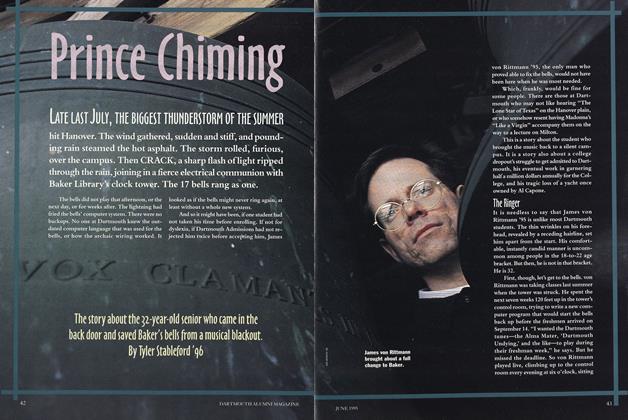

FeaturePrince Chiming

June 1995 By Tyler Stableford '96