The conventions

I am leaving tonight with New York's delegation of Unnecessary Delegates. They preach economy, and here are hundreds of thousands of dollars being wasted to ship all these Destructive Delegates to a place to announce something that everybody in the United States knew six months ago. He [Coolidge] could have been nominated by post card....

WHAT the comic genius of Will Rogers, an astute observer of the American political scene, was saying 54 years ago is being echoed today in other words, in other ways, for other reasons, by political scientists Denis Sullivan and Robert Nakamura of Dartmouth's Government Department: that delegates to nominating conventions are there mainly to ratify decisions long since made. (The analogy should be strained just so far, however; neither Sullivan nor Nakamura has received 22 votes on the first ballot, as Rogers did in 1932.) And, while the parallel holds in their conclusions that convention delegates have very little to do with the ostensible raisond'etre for the whole affair - nominating their party's presidential candidate - the reasons differ diametrically. In Rogers' day, it was the professional politicians in the proverbial smoke-filled rooms who preempted the delegates' deliberations; these days, it is more likely the folks back home, through their votes in either state primary or state convention, who have already committed them to a candidate.

Placing homo politicus (sub-species: convention delegate) under the figurative microscope and watching the individual and collective wiggles has become a quadrennial exercise for Sullivan and an evolving group of his colleagues and students. They have been examining the changing function of political conventions from the 1972 Democratic assemblage, first to work under new reform rules adopted largely in reaction to the disarray of 1968, through both parties' 1976 conventions. The idea has been to figure out whether the wiggles constitute an exercise in futility or whether they have meaning for the political life of the nation - whether the nominating convention is the appendix of the body politic, persisting vestigially among the guts of the political process but bereft of the function it once had.

Sullivan, who came to the College as a full professor in 1968, and the late Jeffrey Pressman formed the nucleus of the investigating team from the start. The most recent addition has been Nakamura, an assistant professor who joined the faculty in 1972. Originally a Dartmouth project, it became multi-institutional through the tides of faculty change: Pressman of Dartmouth became Pressman of M.LT. in 1973, and one of his colleagues there moved on in due course to Yale. Working with "Sullivan et al." - to borrow the bibliographical reference used for their collective publications - has been a shifting group of students: advanced-degree candidates from M.I.T. and Yale, from Dartmouth almost entirely undergraduates. The latter, Sullivan adds proudly, "have performed on a par with the graduate students."

With the support of the College and, at various times, the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Ford Foundation, the team has sampled the attitudes, perceptions, and preferences of a randomly selected group of several hundred delegates by written questionnaire shortly before the conventions and then followed up with interviews at the conventions and occasional questionnaires thereafter.

Their conclusions have been published in two books - The Politics of Representation, based on the 1972 Democratic convention, and Explorations in ConventionDecision Making, which covers both the 1972 convention and the Democrats' 1974 mid-term charter conference - sections of other books, and a number of articles in professional journals. The most recent is a series on the 1976 Republican convention, which took up the better part of last winter's issue of Political ScienceQuarterly.

Although the group has been subjecting Democrats to their scrutiny since 1972, the 1976 convention was the first Republican assembly they had covered. And they found that, indeed, there are differences between the parties and the way they go about their tribal rites - just as a lot of people, Will Rogers included, had suspected all along.

"R EPUBLICANS are neater, and they speak more grammatically," says Sullivan. As a body, they tend to be "more structured, with fewer special-interest groups. They are more homogeneous, heavily middle-class, whereas the Democrats have a lot more variety." The two men share a distinct impression that "Republicans view back-room politics with a faint distaste, that they fundamentally don't like politics." Republicans have specifically rejected the kind of extensive reform that has rocked the Democratic Party: "they don't want to 'McCarthyize.' " Sullivan seems to be saying that Republicans as a whole are better behaved. "No, it's not that they're not given to raucous behavior," he replies. "It's just raucous behavior of a different sort." A notable contrast is that Republican conventions are far better organized at the top than Democratic. "They tend to run on schedule."

A comparison of the women's groups adds an entire new dimension, Sullivan suggests. "While Republican women are intelligent and well educated in general, they have very little clout compared with their Democratic sisters - largely because they don't and won't caucus. Perhaps they don't consider it lady-like. Democratic women, on the other hand, tend to be much more professional and more outspoken."

Each party's partisans, in conversation at least, see the other's in stereotype: Republicans as rich, greedy, and heartless; Democrats as rather scruffy, soft-headed, given to radical notions. In point of fact, Nakamura and Sullivan agree, "the parties are becoming less and less distinguishable in the issues they emphasize during campaigns." As to whether the partisans really believe the stereotypes they promulgate, both men deny an inclination for mindreading. "Who knows?" says Sullivan. "We wanted to get below the conventional level in our surveys, but not too far."

Manners and images notwithstanding, the major parties share in a common historical trend, the researchers have found. The function of the national conventions has altered drastically, perhaps more in the last decade than in all the years since a group of Federalists met in secret in New York City to decide that Thomas Pinckney was to be their party's candidate for President in 1808. "Party nominating conventions," members of the team agree in the general introduction to their separate articles on Republicans assembled in 1976, "may have permanently lost the function of actually choosing a presidential nominee and serve now simply to ratify the winner of the primary campaign." What a burgeoning primary-election system has not done to weaken the power of party organizations, the reform rules have, particularly in the case of the Democrats.

"Since World War II," Sullivan writes, "the percentage of delegates committed to a candidate before coming to the convention has sharply increased." In 1960, he points out, only 40 per cent of delegates had been elected in primaries held in 17 states and the District of Columbia. By 1976, according to the CongressionalQuarterly, the ratio had changed sharply to 75 per cent elected in primaries in 29 states and the district. While some are only "beauty contests," whereby voters can indicate their preferences among the candidates, most are binding on the convention delegates.

The uncommitted delegate is not irrevocably extinct, although it is an increasingly endangered species. The genuinely uncommitted, who actually attends the convention to study the platform and listen to the candidates before deciding how to vote, now exists "only very occasionally," says Nakamura, recalling one such at the 1976 Republican convention. "Under West Virginia law," he explains, "all he had to do was pay $10 to get his name on the ballot. By some fluke, he got elected. From then on, he had a great time. He had lunch at the White House with President Ford, and he was driven around Kansas City with Reagan in his motorcade." For a time, of course, there seemed a strong possibility that it might be the first multi-ballot convention since 1952 - the first for the Republicans since Thomas Dewey won the 1948 nomination over Earl Warren on the third roll call. Although Ford ended up beating Reagan on the first ballot, an uncommitted delegate was an enticing target for hot pursuit.

Reform for the Democrats followed the 1968 brouhaha, when police and protesters rioted in the streets of Chicago and party professionals chose Vice President Hubert Humphrey as the nominee over Senator Eugene McCarthy, despite the fact that McCarthy and the late Senator Robert Kennedy had between them won 70 per cent of the primary ballots cast. The new guidelines included procedural changes aimed at bringing the delegate-selection process out of the smoke-filled room and into the public arena and others mandating more proportionate representation of women, minorities, and the young.

"Historically," Sullivan wrote in the study of the Democratic Party in the seventies, "state delegations have been thought to be the key units for bargaining in conventions; operating under the unit rule [by which state delegations cast their votes as a bloc], they bargain with each other and with candidate organizations. The rankand-file delegates are manipulated by hierarchical leaders holding important positions in national, state, or local party organizations. In order to enhance their bargaining position, these leaders often try to stay uncommitted to any candidate until the moment that their endorsement is crucial to victory for the ultimate nominee...."

Now, with the selection process out in the open and most delegates elected on the basis of their declared commitment to a specific candidate, the struggle for power has shifted to the candidates' organizations during the months leading up to the conventions. And, with special-interest groups heavily represented at the conventions, the caucuses - women's, blacks' and so on have come to rival the state organizations as bargaining agents with the candidates.

His delegate count already over the majority needed, Jimmy Carter arrived at the 1976 Democratic convention with his nomination already assured. "The Carter organization," Nakamura and Sullivan and their colleagues later observed, "exercised substantial control over convention business and was viewed by a large majority of delegates as the most important group at the convention. . . . Black and Women's Caucuses showed new sophistication....In 1972, these groups had existed as largely debating societies; in 1976, group leaders were able to engage in concrete negotiations with the nominee."

THE fact that the overwhelming majority of delegates arrive at a convention with their minds already made up, and often with their votes legally committed -or that Jimmy Carter, in Will Rogers' terms, could have been "nominated by post card" in 1976 - is not to say that the conventions no longer serve a useful purpose. Their most important current function is "legitimation," which Nakamura and Sullivan define as "the belief among delegates that the procedures and decisions of the convention were fair and proper and that, as a consequence, its selections should be supported in the general election campaigns." Disappointed delegates do find satisfaction in "certain divisible prizes that are still allocated, such as platform planks that express their policy views, opportunities to hear their leaders, a vice-presidential nominee who is one of their own, and rules changes that they hope will work to their advantage in the future." Although these are consolation prizes that pale before the presidential nomination, they still "contribute to the losing delegates' willingness to support the final outcome." And the convention also remains the time and place that various groups enjoy their greatest bargaining power over the candidate.

The reform rules have provided a hospitable climate for the emergence of groups of issue-oriented ideological purists as powers to be reckoned with in the nomination process. Issue activists Sullivan defines as "people who come to support a candidate as the principal spokesman for a particular point of view." Party-oriented activists, on the other hand, "justify their commitments in terms of the candidate's capacity to unify the party and win elections." The purist, furthermore, "arrives at a platform that is correct according to some conception of the public interest or good. For the professional, the platform is correct if it placates the losers without alienating the winners and, at the same time, increases the chances of winning the general election." Supporters of Eugene McCarthy in 1968 and Ronald Reagan in 1976 are classic examples of ideological purists who were attracted to candidates on the basis of specific issues.

Some political scientists contend that the issue activists, more often than not middleclass ideologues with little or no party loyalty, representative of causes rather than of the rank-and-file of either Republicans or Democrats, are partywreckers who will eventually weaken the organizations to the extent that voters will be alienated from the two-party system. Not so, Sullivan and Nakamura argue. Citing the disasters which befell the Republicans in 1964 and the Democrats in 1972, they claim to the contrary that it was in both instances the party professionals who failed to unify behind the duly nominated candidates, Barry Goldwater and George McGovern. "It can be demonstrated," Sullivan asserts, "that the activists will legitimate the results of a convention if they come to believe that their issues will be represented by the nominee."

In 1976, they point out, supporters of insurgent Ronald Reagan on the one hand and a spectrum of Democratic candidates on the other generally came around to ratifying the conventions' choices and went on to work for their parties' candidates in the general election. The price of disunity was perhaps not lost on either side, although the Democrats' recollections may have been more vivid. As one platform aide put it after the party's 1975 issues conference, where the thorny question of a stand on bussing was settled amicably, "We could tell that the tone would be geared to compromising and winning the election. Everybody knew that the last time we'd fought we got Nixon - and nothing could be worse than that."

The obvious alternative to conventions as vehicles for choosing presidential candidates is national primaries, a prospect Nakamura considers undesirable, if not infeasible. "No one has ever come up with a formula that would work. What would it take to win, for example - a plurality or a majority? If only a plurality were needed and three candidates were on the ballot, one could win the nomination with only 34 per cent of the vote. If, on the other hand, a majority were required, it could mean a compulsory run-off, for a total of three nationwide elections to choose a president." Aside from practicability, Nakamura's main complaint is that "a national primary would reward the candidate with the best recognition. It would reward incumbency, money, organization." A more likely possibility, he thinks, is regional primaries, a trend already clearly in evidence.

If it sometimes seems that increased emphasis on the primaries has made presidential campaigns a year-in, year-out proposition, it may only be, Sullivan says, that 'the explicit process is starting earlier. If you're an obscure candidate, announcing early may be the only shot you've got." As for more prominent figures, "Very few decide to run only in the last year; they may not start campaigning until then, but they're already running."

TURNING, however reluctantly, from their usual contemplation of the political past to the crystal ball, Sullivan and Nakamura agree that President Carter will probably receive the nomination for a second term. His pre-Camp David slump in public regard they attribute to the differing dimensions of the goals he set himself as a candidate and those imposed on him as President. "Carter was very successful in the primaries," Nakamura suggests, "because he set proximate tasks, goals he could achieve with moderate resources. Given his compartmentalized appeals - separate appeals to women, to religious people, to Mexicans, to technicians - he was able to mobilize support on a candystore basis. As President, he hasn't been able to achieve the large goals - world peace, universal human rights, solution of energy problems, getting his legislative program through the Congress - that both external circumstances and he himself have set."

Whether or not Senator Edward Kennedy will challenge the President for the nomination depends on the turn of events between now and the 1980 primaries, in Sullivan's opinion. "The greatest resource for Kennedy," he posits, "is that, given current economic conditions, Carter must adopt policies that go against the grain of the natural Democratic constituencies - on oil, on the dollar, on social programs. So Kennedy's strategy is to push national health insurance, for instance, try to force Carter into opposition, then see what effect that has on the Democratic coalition. If the President's constituency falls to pieces, then Kennedy will be ready."

Even if he is genuinely uninterested in the presidency, removing himself categorically as a possible contender would be to Kennedy's disadvantage, Sullivan suggests. "Aside from his natural dynamism, Ted Kennedy has influence and gets attention precisely because he is a presidential possibility. He has the power to achieve goals just because he is being considered. Once you become a presidential possibility, people who want something - from the cabinet level down - gather around. They're anxious to help - just in case."

The crystal ball shrouds the Republicans in haze. "The nomination is up for grabs," the prognosticators agree. "It could be a long list, like the Democrats' in 1976," Nakamura suggests. "If"Ford and Reagan are not the front-runners," Sullivan adds.

The issues in the 1980 elections, both men predict, will clearly be energy, stability of the dollar, and the possibility of a depression. "We are very likely to be in a worse position by 1980 than we are now, as far as the economy and oil are concerned," Sullivan says seriously. "But the rest of the world has a big stake in what happens to us."

For all the crises ahead, it seems likely that we shall muddle through - grassroots politicking, convention shenanigans, and all. As Sir Winston Churchill once reminded the House of Commons- celebrated for its own time-honored sort of raucous behavior: "It has been said that Democracy is the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time."

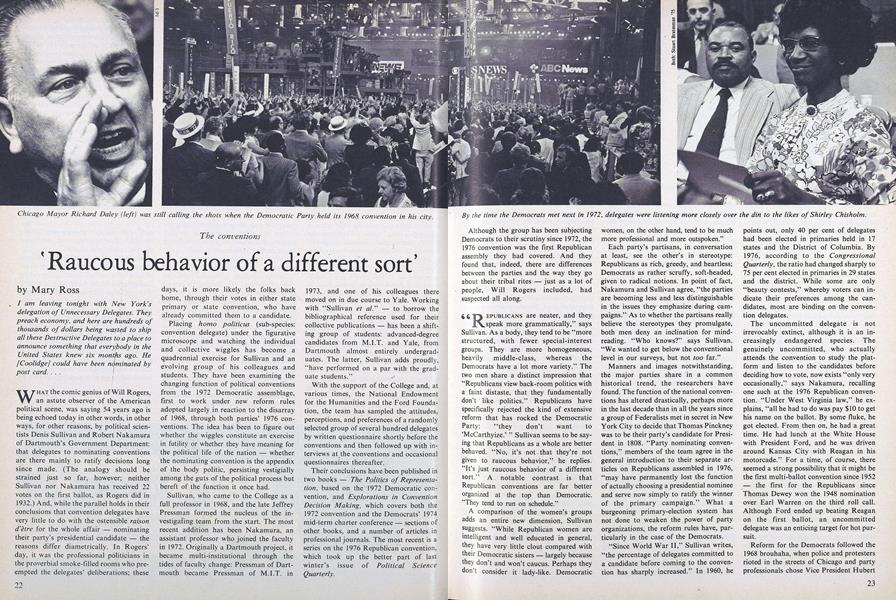

Chicago Mayor Richard Daley (left) was still calling the shots when the Democratic Party held its 1968 convention in his city.

Chicago Mayor Richard Daley (left) was still calling the shots when the Democratic Party held its 1968 convention in his city.

By the time the Democrats met next in 1972, delegates were listening more closely over the din to the likes of Shirley Chisholm.

By the time the Democrats met next in 1972, delegates were listening more closely over the din to the likes of Shirley Chisholm.

A Wallace delegate listens skeptically to goings-on at the Democrats' 1972 convention, while Senator Humphrey presses the flesh.

A Wallace delegate listens skeptically to goings-on at the Democrats' 1972 convention, while Senator Humphrey presses the flesh.

President McKinley accepted nominations and directed campaigns from his front porch. McGovern went to a delegate's head.

President McKinley accepted nominations and directed campaigns from his front porch. McGovern went to a delegate's head.

Mary Ross is associate editor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCrime and Punishment

December 1978 By Tim Taylor -

Feature

FeatureParadise Lost or Paradise Regained?

December 1978 -

Feature

FeatureGOOD NEWS

December 1978 -

Article

Article'Most Improved Professor'

December 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Article

ArticleStraight Shooter

December 1978 By D.M.N. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

December 1978 By DAVID R. BOLDT

Mary Ross

-

Feature

FeatureAnti-Bigot

JANUARY 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureThe Nautical Nyes

MAY 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticlePrairie Ornithologist

NOVEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureSCOPE: Off-Campus Options Made Easier

MAY 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureEditors' Editor

JUNE 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleStrict Reconstructionist

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Mary Ross

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

MARCH 1978 -

Cover Story

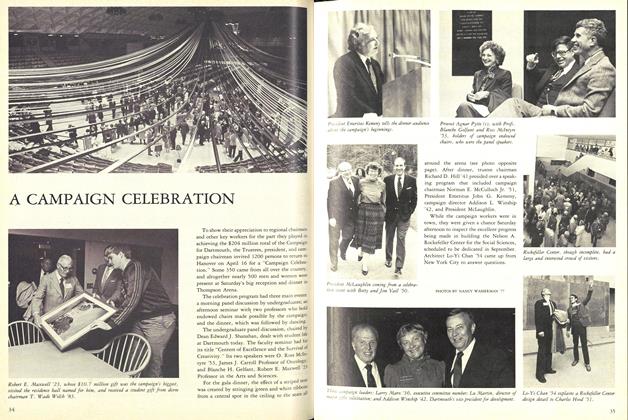

Cover StoryA CAMPAIGN CELEBRATION

MAY 1983 -

Feature

FeatureMEDIA MONSTER: The Rise of Rankings

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

FeatureThe Outward Look

JANUARY 1959 By BEVAN M. FRENCH '58 -

Feature

FeatureGood Teaching: A Case Study

February 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureBuilding a Better Student Body

OCTOBER • 1987 By Thurman Zick