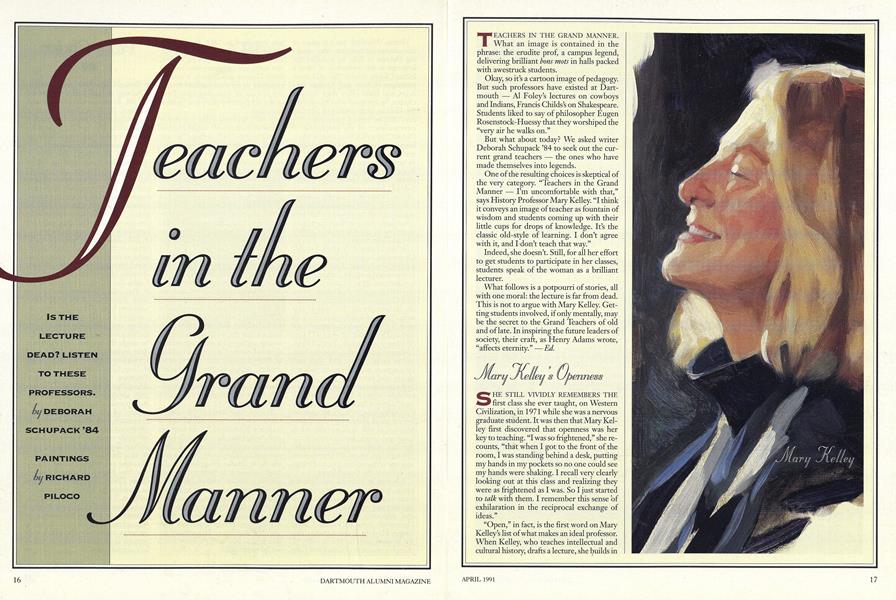

IS THE LECTURE DEAD? LISTEN TO THESE PROFESSORS.

PAINTINGS

Teachers in the grand manner. What an image is contained in the phrase: the erudite prof, a campus legend, delivering brilliant bons mots in halls packed with awestruck students.

Okay, so it's a cartoon image of pedagogy. But such professors have existed at Dartmouth Al Foley's lectures on cowboys and Indians, Francis Childs's on Shakespeare. Students liked to say of philosopher Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy that they worshiped the "very air he walks on."

But what about today? We asked writer Deborah Schupack '84 to seek out the current grand teachers the ones who have made themselves into legends. One of the resulting choices is skeptical of

the very category. "Teachers in the Grand Manner I'm uncomfortable with that," says History Professor Mary Kelley. "I think it conveys an image of teacher as fountain of wisdom and students coming up with their little cups for drops of knowledge. It's the classic old-style of learning. I don't agree with it, and I-don't teach that way."

Indeed, she doesn't. Still, for all her effort to get students to participate in her classes, students speak of the woman as a brilliant lecturer.

What follows is a potpourri of stories, all with one moral: the lecture is far from dead. This is not to argue with Mary Kelley. Getting students involved, if only mentally, may be the secret to the Grand Teachers of old and of late. In inspiring the future leaders of society, their craft, as Henry Adams wrote, "affects eternity." —Ed.

SHE STILL VIVIDLY REMEMBERS THE first class she ever taught, on Western Civilization, in 1971 while she was a nervous graduate student. It was then that Mary Kelley first discovered that openness was her key to teaching. "I was so frightened," she recounts, "that when I got to the front of the room, I was standing behind a desk, putting my hands in my pockets so no one could see my hands were shaking. I recall very clearly looking out at this class and realizing they were as frightened as I was. So I just started to talk with them. I remember this sense of exhilaration in the reciprocal exchange of ideas."

"Open," in fact, is the first word on Mary Kelley's list of what makes an ideal professor. When Kelley, who teaches intellectual and cultural history, drafts a lecture, she builds in questions and room for speculation places where, she feels, the real learning occurs. "Lecturing as an approach to teaching is almost a necessity, but a lecture that doesn't have a lot of interaction is for me not a success," she says. "Students can tell you: if I don't have much verbal response I will stop, say, a third of the way into the lecture. I'll ask them what they think. I tell them I'd be bored listening to myself for a whole hour. That causes a lot of laughter, then it does open conversation."

She encourages interactive lectures by seeking controversial material, like the Vietnam War, McCarthyism, Puritanism, reasons for the Civil War material to which students might bring their own opinions to the study of history. "For example," Kelley explains, "everybody who walks into my class thinks Puritanism was an awful thing."

She seeks interaction not only through the material but also in her relationships with students. When a class goes poorly "you can see it in the very looks on their faces" she seeks feedback from students whom she sees in office hours or around campus. "The myth notwithstanding, students are very honest and gracious and friendly," she says, speaking in her soft, almost confidential tone. "If they trust you, they'll be honest back."

Furniture is not safe in 102 dartmouth Hall. Clothing is not safe. Nor is decorum. Nor inhibitions. The Rassias Method, used internationally by colleges, business groups, and others, weaves drama with total immersion in a foreign language. Under his tutelage, and now that of most Dartmouth language professors, students learn enough of a foreign language in two terms to study overseas for a third. Rassias's teaching philosophy is emblazoned on a T-shirt hanging over his desk: Il faut être humain (You must be human).

The class in 102 Dartmouth Hall is French 2. An oft-repeated phrase here is unepetite éxperience a little experiment. To prepare for the biggest of today's little experiments, students shut the shades, turn off the lights, and, as naturally as opening a blue book for an exam, pull brown paper bags over their heads. "Do not," the professor says, his deep voice resonating in the darkened room, "under any circumstances, no matter what happens, take the bags off until I tell you. Anyone here with a weak heart?" Indeed, Rassias's classroom is no place for a weak heart. He bangs his desk. He throws a chair and its back breaks; he uses the loosened panel to bang students' desks. He grunts, makes animal noises, claps bagged students on the shoulders.

Each "petite experience" has a message. When the lights go on and bags come off, Rassias elicits students' reactions to having their sight cut off: "bizarre," "scary," "like you're in a zoo" (all this in French, of course). That is how they will feel, he explains, if they go to France with figurative bags over their heads, shutting their eyes to the culture. "You've got to speak French in the skin of the French," he urges students, most of whom will live in France for a term through the Language Study Abroad program. "When you go to France, do not take the sun, stars, and moon of Hanover with you. Live under the sun, stars, and moon of France."

Rassias believes deeply in tactile teaching, believes his message shines through his madness. He tears apart his shirts "and they're good shirts" to symbolize breaking through one's inhibitions; a seven-foot inflatable Godzilla "the ultimate existential hero: he's defined strictly by his actions, doesn't have a brain in his head" hangs from his office ceiling.

"The intellect functions best while fueled by emotion," Rassias says. "You have to hit them with a megaton of emotion." Which is exacdy what you'll find in French 2: he sits on a student's lap to coax an answer, then kisses the student's head in approval. "People connect this way," the professor explains later. "It's as the faith healer says: Touch someone and their whole body's metabolism changes."

Another student is called to the front of the room to give an informal personal history in French. When he finishes, Rassias genuflects before him. "He was perfectly poised, spoke excellent French. Why shouldn't I bow in front of the kid?" Then, after one explosive hour, class is over.

"Au revoir, mes enfants," he says as students file out.

"Au revoir, papa," they answer. "I'll go to any extreme to make the point," he says after class. "Take any risk. Frankly, I'd rather die of exhaustion than boredom."

It could be cambridge, circa 1950. OR Hanover, any time from 1960 to 1990, if the professor is Vincent Starzinger. In coat and tie, calling students Mr. or Miss LastName, the government professor bespeaks the academe of old with the "Paper Chase" rigor and formality of his classes. His name or his nickname, "The Zinger" conjures in students a mix of reverence, intellectual excitement, and fear.

"He's really a bulldog for intellectual rigor," says David Burwell '69, who studied with Starzinger, "my favorite professor," more than 20 years ago. "I had him for an introductory course as a freshman, and I wasn't used to being treated as an adult. From the first day he treated students as colleagues. It was scary at the start, but then it was extremely attractive to me."

Starzinger cuts a sharp figure on campus conservatively dressed, his gray hair closely cropped. ("I always liked that fact in the late sixties, when everybody was counterculture, he always cut a very dapper figure," recalls Burwell.) Starzinger, a political conservative, is known as a man of military discipline, both in his classroom and out on the lonely Connecticut River, where he rows his single skull almost every day from May through November.

He can be elusive and offputting. "I don't talk about teaching school," he says by way of declining to be interviewed. "I do it. I don't talk about doing it."

But for students who discover the man behind the myth, Starzinger is rife with intellectual challenge, respectful of opposing (read: liberal) opinions, and eager to participate in what Burwell calls "sympathetic debate over political philosophy." Burwell says, "The two people who've had the most influence on my career and Vince isn't going to like this are Vince Starzinger and Ralph Nader. I still think, 'What would Vince Starzinger say about this?'"

VinceStarzinger

ROBERT JASTROW HAS AN IMPORTANT story to tell: nothing short of the genesis

of the universe, Earth, and man. "It's the most interesting form of science a story that stands alongside the great ideas of Western religion," says Jastrow, professor of Earth Sciences, nationally known astronomer, and author of science-for-the-amateur books that sell in the millions. "It's a story everyone should know."

Throngs of Dartmouth students who have graduated in the past two decades do know the story of cosmic evolution, thanks to the College's traditionally most-enrolled class, Jastrow's Earth Sciences 5, better known as "Earth, Moon, and Planets." It has become a sophomore-summer staple (one-third of registered students took the class in the summer of '89) and is the science-distributive option for the "unwashed," as Jastrow jokingly calls non-science majors.

Jastrow speculates on the course's popularity: "The way it presents science is appealing: placing all the main facts and ideas of astronomy, geology, and the evolution of life into one chronological context, telling the genesis of life through a direct chain of events. Then finally man appears on the earth it's quite illuminating." He pauses. "It certainly can't be because of my jokes."

Last summer marked the first time in 20 years Jastrow did not offer the course, deferring instead to his research on global warming. Did he like hundreds of bereaved '92 s miss Earth, Moon, and Planets? "Sure," he says, with a shy-looking crescent-moon smile. "Like when somebody stops hitting you on the head with a hammer." He explains, "It's a lot of work, but I like it."

Jastrow whose not-always-down-toearth subject matter has earned him the moniker "Astro Jastrow" among students often finds himself in the middle of nationwide controversy, ranging from the extinction of dinosaurs (see "Dino Wars" in the February '90 issue) to the merits of the "Star Wars" nuclear-defense initiative. But life in the classroom is less mercurial. "I think I have good rapport with my students," Jastrow says. "I enjoy figuring out how to explain complicated matters to them. In the art of teaching, you must encourage students because great things might happen."

THERE ARE MORE PEOPLE IN DONALD Pease's classroom than meet the eye. There is the teacher and the student, of course; but there's also the student inside the teacher, and the teacher inside the student. Pease, who specializes in American literature and drama, says his goal is to activate the teacher inside the student. "I love to see the teacher in the student come to life," he says. "The recognition in the student that she can teach herself—she or he does not have to depend on an instructor to learn, and will make learning a lifelong pleasure instead of a burden."

How better to tap the teacher in the student than by uncovering the student inside the teacher? "The teacher has to reawaken the student in himself to address the student in the class," Pease explains.

If things sound busy and noisy inside Donald Pease, they are. Talking with Pease is a complex affair. Although he looks deceptively boyish with excitable blue eyes, slightly tousled brown hair, and wearing jeans he hits a listener with ideas that have many strands and are often presented in an elaborate macrame. Such as the explanation of how he prepares for his classroom lectures, which are among the most popular on campus:

"I combine what I did before, in previous years, with what I'm presently thinking about. The lecture is the interface between what I think I know and what I presently know I don't know."

Pease's teaching method relies on both lecture and seminar classes. "Alecture," he says, "requires a finished formulation of the material, whereas a seminar requires a very engaged and participatory sense of the material. What's finished [in a lecture] is constantly getting dismantled by group discussion." A seminar, he adds, is when the teacher "begins to unlearn."

Why, then, bother to present a finished lecture if its arguments are only going to be dismantled later? The answer is distinctly Peasean, an

elaborate entangling of ideas: "A lecture is like putting a net in a stream. You can say, 'Given the fluidity of the process, these are the fish we can net at this particular time with this particular net.' But you never lose the sense that the flow is proceeding. And you have to keep in mind there are other meshes of net, larger or smaller holes depending on the fish you want to catch. You can also fish closer to shore, or farther from shore."

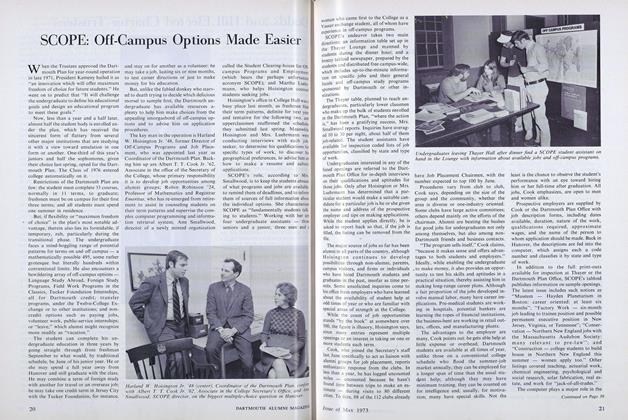

BILL COOK IS A POET, AN ACTOR, A storyteller, and a scholar. In other words, he is a teacher. "All those other things I do are part of me as a teacher," says Cook, professor of English and former chairman of Afro-American Studies. "I bring whatever skills I have as an actor into class. I certainly don't have the standard, cliché academic temperament: objective, dignified, detached. I don't think I'm any of those."

Cook is a flamboyant and familiar figure on campus, with his rich voice (ideal for the annual Halloween ghost-storytelling at the Top of the Hop), sweeping gestures, dramatic white handlebar mustache and beard, and always-open office door in the basement of Sanborn Hall. He frequently reads to his classes "Lord, do I ever!" and is constantly trying to extend the canon for them. His syllabus for English 5, freshman English, includes Native American writers, blacks, and women, as well as white men.

For Cook, the ideal teaching schedule combines the large lecture class and the small seminar. "In a larger class, it is physically impossible to accommodate that individual contact you have in a seminar-size class. But I'm an actor so I like a large lecture. Ta da!" he says, spreading his arms with an onstage grandeur. "I get to perform."

Cook subscribes to the get-'em-while they're-young doctrine of any good zealot, his mission being teaching. He devotes each fall term to teaching freshmen, and he is a committed member of the National Faculty of Arts and Sciences, a group of 700 college professors who consult with elementary and secondary school teachers throughout the country.

"I can't remember ever wanting to be anything but a teacher," says Cook, who taught public school in New Jersey for 20 years before coming to Dartmouth in 1973. He does, however, admit to a flight of fancy as a young child: "I did want to be an opera singer. Only problem was, I lacked the voice. But in a sense I did succeed; I think of my teaching as operatic loud, dramatic, extreme. I love to whoop and bellow."

Mary Kelley

John Rassias

Robert Jastrow

DonaldPease

Bill Cook

Mary Kelley's Openness

I TELL THEM I'D BE BORED LISTENING TO MYSELF FOR A WHOLE HOUR."

The Passion of John Rassias

The Zinger

HIS IDEAS AREOFTENPRESENTEDIN ANELABORATEMACRAMÉ.

Pease and Cues

Cook's Deliqht

HIS NAME CONJURES IN STUDENTS A MIX OF REVERENCE, EXCITEMENT, AND FEAR.

Earth, Moon, and Jastrow

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Recent Interview with Ernest Martin Hopkins' 01

April 1991 -

Feature

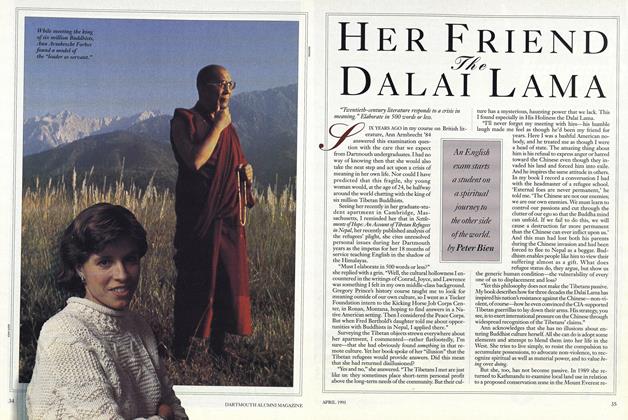

FeatureHer Friend the Dalai Lama

April 1991 By Peter Bien -

Feature

FeatureSTEVE KELLEY IN TWO ACTS

April 1991 By ROBERT ESHMAN '82 -

Feature

FeatureCOULD I GET IN TODAY?

April 1991 -

Feature

FeatureDisengagement

April 1991 By John Sloan Dickey '29 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

April 1991 By E. Wheelock