The split between the impulse to dominate nature and the urge to celebrate it constitutes the tragedy of our species.

TWO accounts of the creation human beings in the Book of Genesis address the question: How can we simultaneously subdue nature and celebrate it? In the first account, an androgynous God "created man in His own image, in the image of God created He him; male and female created He them." God's first commandment to Adam and Eve is to reproduce: "Be fruitful and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth." This Darwinian injunction has been taken to heart, so to speak, by every gene in every human, animal, and plant ever since. Evolution has been driven by the principles of replication and survival. Humankind's dominion over nature represents a distinction between people and animals, but only in terms of power. The earthly hierarchical chain of domination ends with us, yet a limit as to how we appropriate other life is implied by the close linking of human beings with the rest of creation.

In the second account of creation, however, the first act that God requires of Adam is the naming of the animals. Adam is told to exercise a very different kind of power: not that of appropriation but of appreciation. The history of poetry, one might say, begins here with the annunciatory power of language. It follows that human creativity, by virtue of the gift of speech, will evolve in response to the natural world: "And out of the ground the Lord God formed every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air; and brought them unto Adam to see what he would call them; and whatever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof." Humankind's ambivalence toward nature the desire to subdue nature and to celebrate it begins mythically with our Biblical origin.

In time, as we now witness to our dismay, appropriation would exceed its original limit of survival and become exploitation, and celebration would shift from acknowledging the otherness of nature as a resource for the imagination—our capacity as namers and diminish into indulgent subjectivity. The ultimate irony that we must now confront is that as a species we may very well fail by succeeding: By subduing the earth and by multiplying beyond any expectation of the Biblical imagination, we may destroy the resources upon which life depends. What once appeared to be God's and therefore nature's infinitude, its capacity to be cultivated without ever being subdued, now appears as a revelation of limits requiring a new commandment of both sexual and acquisitive restraint—a restraint which our genes are not designed to comprehend or enact.

A respect for nature's otherness should, however, prevent us from being sentimental about nature's awesome beauty. Nature's cruelty and indifference to suffering and loss, and thus the need to subdue its forces, was well understood by the Biblical imagination and has been restated with great vividness many times subsequently. In Darwin's words: "As more individuals are produced than can possibly survive, there must in every case be a struggle for existence, either one individual with another of the same species, or with the individuals of distinct species, or with the conditions of life." John Stuart Mill, in his unflinching essay, "Nature," expressed the same realization: "Nature impales men, breaks them as if on a wheel, casts them to be devoured by wild beasts, burns them to death, crushes them with stones like the first Christian martyr, starves them with hunger, freezes them with cold, poisons them by the quick or slow venom of her exhalations, and has hundreds of other hideous deaths in reserve." The contemporary historian of the changing concepts of nature, Roderick Nash, in Wilderness and the American Mind, describes the modern idea of wilderness as usually positive, as in Gerard Manley Hopkins's lines, "What would the world be, once bereft/ Of wet and wildness? Letthem be left,/ O let them be left, wildness and wet,/ wildness and wet;/ Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet." Nash contrasts this modern attitude with the "ancient Hebrews [who] regarded the wilderness as a cursed land and associated its forbidding character with a lack of water." Conversely, as Nash points out, "when the Lord wished to express his pleasure, the greatest blessing he could bestow was to transform wilderness into a 'good land, a land of brooks and water, of fountains and springs.'" It would appear that only because nature and wilderness had already been largely subdued by civilization that Thoreau was free to declare in his essay, "Walking," that "Wildness is the preservation of the World" or that "The most alive is the wildest. Not yet subdued to man, its presence refreshes him." Wilderness "refreshes" for Thoreau because it carries with it the association of water rather than the desert's association with barrenness.

In the course of civilization, and with unprecedented intensity in the nineteenth century, poets have emphasized the power of the human mind over the power of nature. These literary namers, however, often failed to acknowledge that artistic creation depends upon a physical world of things and creatures that have existed prior to them. Indeed, the forms that nature has evolved are more various than poets could have contrived from their most fervid imaginations. Nature provides the images from which poets make their metaphors, so a world where fewer creatures thrive diminishes the resources that inform our capacity to invent symbols. Without the snake, for example, our ability to evoke a sense of evil would be lessened. With industrialization and technology, the balance between domination and appropriation on the one hand and celebration and naming on the other has taken a fatal shift.

The prophetic passage in the Bible that no doubt anticipates that fatal shift toward aggressive domination can be found in Genesis, chapter nine. After the flood has abated and Noah leaves the ark to make his residence again on the land, God reaffirms His covenant with Noah and gives him the same Darwinian commandment that He gave to Adam: "Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth." But now, perhaps in recognition of some endemic predatory instinct in human nature, God chooses to permit human beings to eat animals as well as plants, thus establishing a terrible separation between humankind and the rest of the animal kingdom: "And the fear of you and the dread of you shall be upon every beast of the earth, and upon every fowl of the air, and upon all that moveth upon the earth, and upon all the fishes of the sea; unto your hands are they delivered./ Every moving thing that liveth shall be meat for you; even as the green herb have I given you all things."

We would do well, through an empathetic act of imaginative projection, to contemplate the "dread" of the animals today. Despite the immemorial and necessary project of civilization to mitigate the random cruelty of nature what Mill asserts as the "undeniable fact that the order of nature, in so far as unmodified by man, is such as no being, whose attributes are justice and benevolence, would have made"—we are destroying our resources of metaphor and therefore limiting our capacity as namers. Species in the animal and plant kingdom are now being brought to extinction throughout the planet at a rate thousands of times faster than in the previous 65 million years. These species, we should remember, took millions of evolutionary years to create. Among the natural catastrophes that brought destruction to life on this planet—such as the asteroid which, colliding with the earth, scattered dust that obscured the sun and killed off the dinosaurs—we, the human species, are the earth's pre-eminent catastrophe. Our dreadful capacity to subdue, to dominate and destroy, always has been inextricably bound to our capacity to name and celebrate. Our salvation as a species lies in the desperate hope that our aggressive instincts may yet remain within the scope of the human will—the will to make civilization itself a work of art that names and celebrates nature, that does not merely replace nature with self-reflecting human images.

Like Adam's initial act of naming the animals, the pictures on the walls of the caves of Lascaux celebrate the grandeur of the animals. They are drawn with incredible grace that contrasts with the few awkward representations of the human figure. In contemplating these depictions of the animals, we can imagine that we are witnessing the human invention of the ideas of beauty. The Lascaux artists' personal renditions are wedded to the observed animals being hunted, just as Adam's names become the names of the animals. We cannot fulfill our role as namers without a world of things, of animals, beyond our own making that have preceded us and helped us define our special function within the mutual creaturely bond as namers.

Naming as a response to what is there—naming grounded in observation and description—can, however, easily collapse into indulgent subjectivity in which self-assertion is given priority over the natural world. When language becomes a form primarily of self-expression, when it abandons its fidelity to the natural world, we no longer can assume a shared understanding about the relationship between an object and its name, or find a solid communal meaning in a text that derives from the design ofnamed things. Communication collapses, and discourse becomes anarchic as in the city of Babel. Wordsworth clearly understood the break down of language as an aspect or an extension of The Fall when he claimed in his appendix to the Preface to Lyrical Ballads (1802) that "the first Poets...spake a language which, though unusual, was still the language of men... [until] diction became daily more and more corrupt, thrusting out of sight the plain humanities of nature." Wordsworth's point is that the directness and simplicity of poetic diction must serve to highlight the actuality of objects, the specific details of divine creation, rather than draw attention to itself. After all, Wordsworth believed, language itself derives from the physical sounds of the natural world:

...and I would stand, If the night blackened with a coming storm, Beneath some rock listening to notes that are The ghostly language of the ancient earth, Or make their dim abode in distant winds.

(Prelude 11, 306-310)

Just as language, according to Wordsworth, derives from the "notes" of the "ancient earth," so too does physical creation, represented by the animals, evoke what is essential about our humanity—our ability to celebrate the natural world by giving names to its inhabitants. The animals that the Lord brought forth for Adam to name are meticulously described by the Lord Himself in the Book of job. Job asks the Lord to explain why evil exists in the world, why good people often suffer for no discernible cause, and why malefactions go unpunished. Replying out of the whirlwind, the Lord circumvents any discussion of the ethical issues raised by Job; rather, God recounts the scope and magnitude of His powers in having cre ated the universe ("Where were you when I planned the earth?"). The divine argument culminates in a long list of the creatures that God has fashioned—a list which (with divine irony) does not include human beings.

There is nothing sentimental in the Lord's depiction of the animals. Invariably, their behavior and their fortunes involve pain and destruction—as Darwin claimed subsequently was the inevitable design of nature—but they are awesome and beautiful nevertheless. It is as if they are there simply to be seen, as if the universe required nothing more in making creation complete than that the animals be named. The Lord describes them to Job in loving detail to reawaken in Job his capacity for wonder and celebration and to remind him of his own finitude within the larger scheme of nature—a cosmic scheme well beyond the workings of planet earth and the designs of human beings.

Do you tell the antelope to calve or ease her when she is in labor? Do you count the months of her fullness and know when her time is come? She kneels; she tightens her womb; she pants, she presses, she gives birth. Her little ones grow up; they leave and never return... Do you show the hawk how to fly, stretching his wings on the wind? Do you teach the vulture to soar and build his nest in the clouds? He makes his home on the mountaintop, on the unapproachable crag. He sits and scans for prey; from far off his eyes can spot it; His little ones drink its blood. Where the unburied are, he is.

(Stephen Mitchell translation)

Such are the images of life, breeding and struggling to survive, given by the Lord to inspire human imagination in its contemplation of the interdependence of creation and destruction. In preceding human existence, either according to Biblical mythology or evolutionary theory, the animals, the forms of the natural world, still hold dominion over the poetic mind, even as human greed and appetite have diminished nature's astonishing plenitude.

To exploit and destroy die plants and the animals is to diminish the source of beauty in ourselves. Sadly this is true despite the bitterly ironic fact that simultaneously as we annihilate our fellow inhabitants on this planet we also pursue the legitimate work of replacing nature's indifference with human empathy upon which morality and the sense of justice are based—as in King Lear's injunction to himself, and to us all, to "Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,/ That thou mayst shake the superflux to them,/ And show the heavens more just." This split between the impulse to take dominion and the impulse toward celebratory respect constitutes the tragedy of our species.

Darwinian wisdom reminds us that we have not evolved as a species designed to solve problems beyond the immediacy of own generation; never before has such prescience been necessary. "Natural selection does not look ahead," says Colin Tudge in The Engineer in the Garden, "and in general is bound to favor short-term advantage over long-term." If being fruitful only means multiplying, then our species will be left without a morality of fruitfulness when the earth no longer can support any further enlargement of the population. The idea of fruitfulness will have to change from numerical increase to some concept of improvement in the quality of life. We as a species need to change ourselves radically through an act of reasoned willa change no species has ever been called upon to accomplish. The power of naming, therefore, that poets must summon today is to name ourselves as devourers gone berserk, as the scourge of the earth, and, perhaps, in the realization of that naming, to reinvigorate our commitment as preservers and our role as celebrators.

The need to enlarge the idea of fruitfulness is inherent in the Biblical text as a warning to Adam about forbidden fruit. Adam is not permitted to transcend nature, and therein lies the fundamental lesson of accepting limits. Because Adam rebelled against his bond with nature by seeking to become immortal, by violating a necessary limit, God sends Adam forth from the garden of Eden "lest he put forth his hand, and take also of the tree of life and live forever." In presuming to take dominion over the planet earth, with only human welfare and comfort in mind, our species has not mastered the universe or taken dominion over the second law of thermodynamics or, most significantly, achieved eternal life that would set the human species apart from the fate of all the other creatures.

With the first human awareness of death as an ongoing state of nonbeing, the desperate wish not to die must simultaneously have been born. This immortal desire is implied in the earliest burial sites in which possessions are placed in the grave to accompany the dead on a journey. But taking dominion, even when that effort aspires to the most glorious aspiration of civilization—to bring empa thy and justice into the world cannot mean that we can possess our bodies for long or that the Yeatsian speculation, "Once out of nature I shall never take/ My bodily form from any natural thing," can ever be realized, except as a fantasy of power in which one gives birth to oneself as if to a work of art. The fantasy of transcending nature and becoming immortal is the ultimate extension of the wish to take dominion over nature and subdue it. But taking dominion over nature can only mean for our species that we will have proven that our particular genius has been the destruction of many wondrous living forms, and finally the destruction of ourselves. No doubt bacteria and cockroaches will survive our folly, or some more adaptable life form will emerge in another solar system. To choose to remain creatures, then, moral creatures, yes, but creatures still, is to accept limits—the limits of morality, the limits of power and possession. We must remember and remain true to our evolutionary origins, not merely as multipliers but as namers as well.

The human imagination continues to depend on natural images and natural beauty, on trees and plants and birds and animals, on the seasons and the weather; without them, the human spirit, nurtured by its own poetic expression of a world of "wildness and wet," is diminished and impoverished. Without a sense of beauty that derives from otherness, from nature's independent existence, a prior world on which our fabricated natural world depends, the capacity for taking delight in our surroundings will have withered away. Even before the planet becomes inhospitable to the human species, we will have died in spirit. Perhaps superintelligent creatures of our own technological creation, based not on carbon but on silicon, who do not depend on food or air or a moderate climate or leisure time for reading Shakespeare, will evolve to survive us in a state of happiness that we, still the children of natural laws, who live, as Prospero says, "'twixt the green sea and the azur'd vault," have not evolved to comprehend.

"Our salvationas a species lies inthe desperatehope that ouraggressiveinstincts may yetremain withinthe scope of thehuman will—thewill to make civilization itself awork of art thatnavies and celebrates nature,that does notmerely replacenature with selfreflecting humanimages."

"In presumingto take dominionover the planetearth, our specieshas not masteredthe universe ortaken dominionover the secondlaw of thermodynamics or,;most significantly, achieved eternal life thatwould set thehuman speciesapart from thefate of all theother creatures."

Called by The New York Times "the trueheir" of Robert Frost, ROBERT PACK teachesat Middlebury College and directs the BreadLoaf Writer's Conference. Among his 32published books is Naming the Sun.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

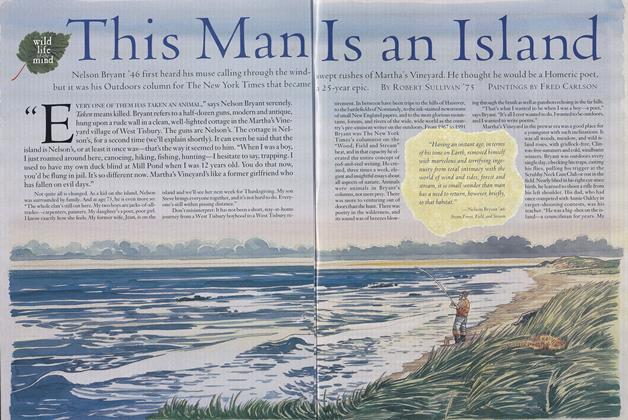

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

October 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

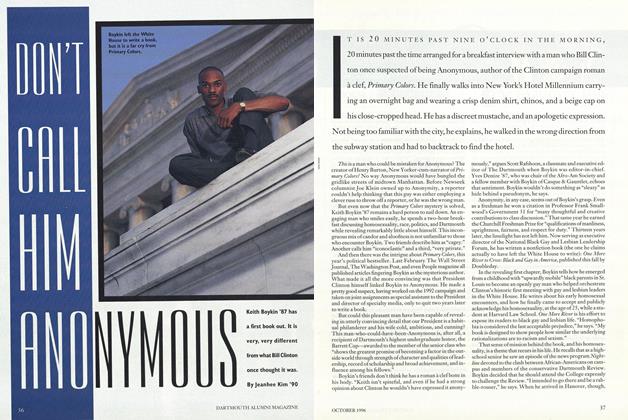

FeatureDON'T CALL HIM ANONYMOUS

October 1996 By Jeanhee Kim '9O -

Cover Story

Cover StorySecond Nature

October 1996 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

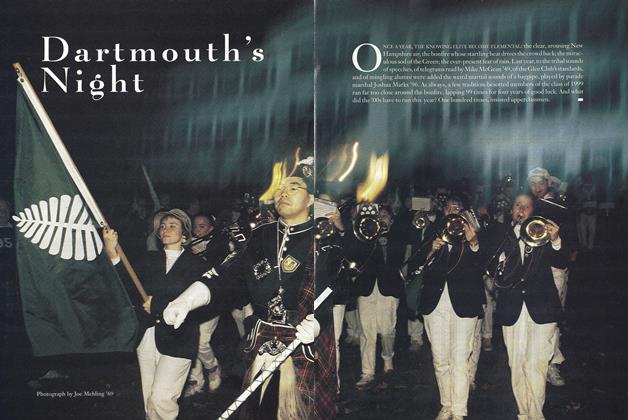

FeatureDartmouth's Night

October 1996 -

Article

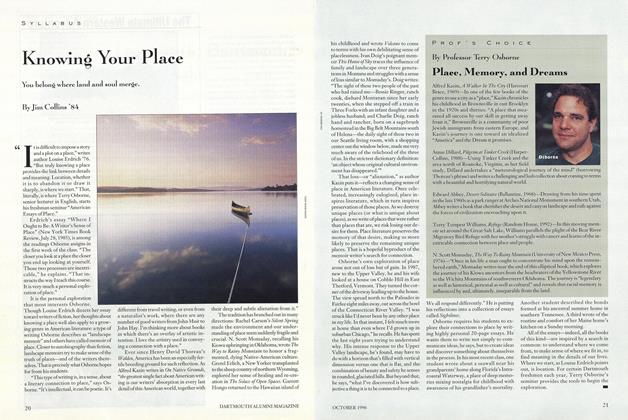

ArticleKnowing Your Place

October 1996 By Jim Collins'84 -

Article

ArticleThe Orange on Campus Is Not on Leaves

October 1996 By "E. Wheelock"

Robert Pack '51

Features

-

Feature

FeatureIvy League bands: The beat goes on

OCTOBER 1972 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThorne Smith 1914

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

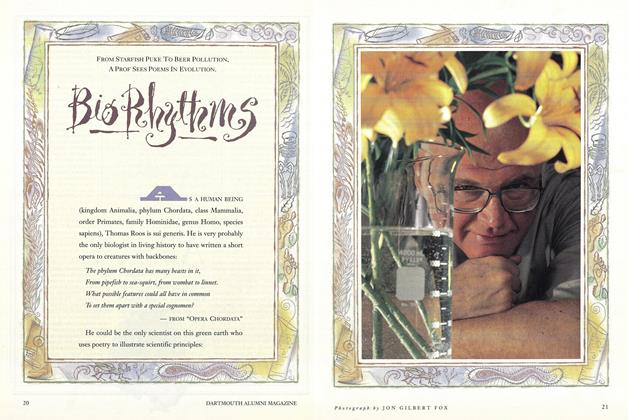

FeatureBio Rhythms

SEPTEMBER 1991 -

Feature

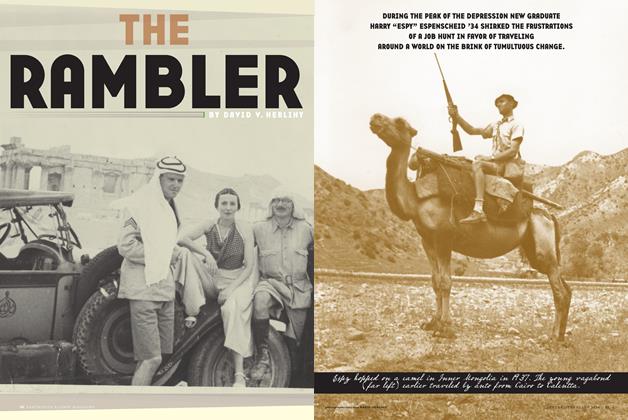

FeatureThe Rambler

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By DAVID V. HERLIHY -

Feature

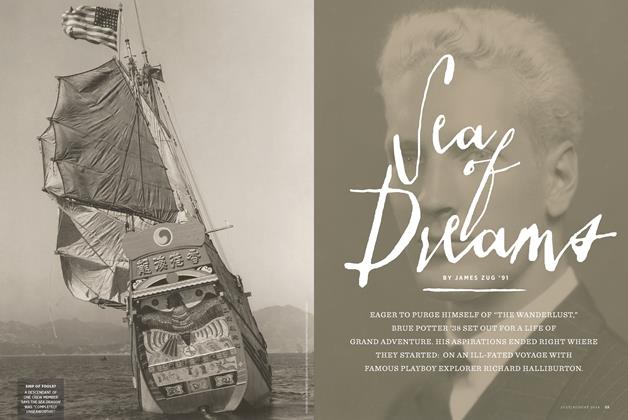

FeatureSea of Dreams

July | August 2014 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

Feature

FeatureEducation's Marshall Plan

JULY 1967 By ROBERT H. WINTERS, LL.D.