Of all the horrors humans have endured during the twentieth century, two refuse to fade into the historical distance. The Holocaust, which destroyed two-thirds of European Jews, and Hiroshima, where 100,000 people perished from the first atomic bomb, remain as scars on the souls of survivors and on the consciousness of their cultural brethren. Like the identification numbers branded onto the arms of concentration camp prisoners and the keloids that mark radiation burns, the Holocaust and Hiroshima are beyond forgetting.

"As historical events, the Holocaust and Hiroshima were of completely different orders of magnitude, but they have produced similar responses and assumed similar places in the cultural imaginations of people," says Alan Tansman, a professor of Japanese language and literature. He and Hebrew professor Shalom Goldman co-teach "Memory and Catastrophe," a course on Japanese responses to Hiroshima and Jewish responses to the Holocaust. One of only two such courses in the nation, the class is a hellish march through the many attempts—literary, artistic, historical, and religious—people have made to come to terms with the traumas.

The very idea that the two events have anything in common disturbs some peo- ple, the professors say. "Sometimes in class I have a flash that my grandparents are asking me how I can compare these two events," says Tansman, whose family left Europe during Hitler's rise. He and Goldman agree that in many respects there are no comparisons. A crucial issue is victimhood. The Jews were unquestionably victims of methodical genocide, unlike the Japanese. Moreover, Japan's role as a victimizer complicates, if not cancels, Hiroshima and Nagasaki being seen as mere victimsthough they undeniably suffered unprecedented horrors in the nuclear attack. Questions of victimhood aside, the very specificity of horrors has surrounded each event with a kind of sacredness that makes comparison taboo, say the professors. "If something is unique, it can't be compared," Goldman explains.

But responses to these catastrophes show similarities born of the human condition and distinctions arising from cultural specifics. "Each society offers people different means to cure their suffering," Tansman says. Some European Jews, for example, have tended to think in Freudian terms—such as overcoming or integrating trauma by talking about it—while psychoanalytic ideas never took hold in Japan. "In the Buddhist sensibility there is a strong consciousness of the impermanence of life, which leads to a kind of quietude that to us can seem passive but can lead to acceptance of suffering and tragedy," Tansman says. "The Japanese are likely to take the view: enough already, don't obsess. Get on with life."

Even so, getting on with life clearly wasn't easy for the hibakusha, the people who lived through bombing. Observations jotted down right after the bomb, memoirs written subsequently, and fully realized literary portrayals of what the hibakusha writer Ota Yoko called "a new kind of death" clearly indicate that the atomic bomb opened a gulf between life before and after the cataclysm. Witnesses described the flash, the unearthly gust of searing heat, and of people caught between life and death, skin hanging in sheets from bodies that still walked. They described the impossibility of aiding all the injured who cried out for help and the ongoing agonies as person after person succumbed to radiation sickness.

Despite such descriptions, the gap between experience and narrative loomed large. "Writers felt numbed by such an unimaginable event," says Tansman. Ota Yoko, who presented herself as the A-bomb writer, insisted that people who hadn't experienced the bomb could never truly comprehend it.

Other writers accused Ota Yoko of being an "A-bomb fascist," but in some respects she was right about experience. The hibakusha had indeed lived through a nightmare, and many survivors of the bomb never fully re-integrated into normal Japanese life. Employers were reluctant to take on lifetime employees who could sicken from radiation at any moment, a permanent time bomb that marred survivors' marriage prospects as well. But Ota Yoko's notion ignores the human ability to empathize and the time-bound necessity of turning individual memories into cultural memorialization. Hiroshima took on an identity as an international City of Peace, its citizens becoming a kind of role model as the first victims of atomic attack with a duty to remind the world of the consequences of nuclear weapons. Each August 6, as the Japanese pray for the dead, people from all over the world join them to pray for peace. Sustaining memory, students make braids of paper cranes as a continuing link to Sadako Sasaki, a 12-year-old girl, who, hearkening back to Japanese legends of cures, tried to fold a thousand paper cranes in an attempt to stave off radiation-induced leukemia.

Within this remembrance, however, lurks the potent matter of what is left out as time passes. As Tansman explains, "The creation of an identity as victims has allowed for great forgetting of their role as victimizers in the war."

Facing parallel issues of memorializing tragedy, Jews want the world to remember the Holocaust in its terrible entirety, even as Jews themselves continue to place the experience in historical and Jewish perspectives. Just after the war, the international community viewed the concentration camps, where the Nazis imprisoned and killed various "enemies of the state," as a universal rather than a Jewish tragedy, Goldman points out. Released from hell, many jewish survivors refused to speak about the horrors they endured. Some other Jews didn't want to know. In the new state of Israel, Goldman tells his class, some Jews looked down upon the survivors as remnant sheep in a herd that allowed itself to be led to slaughter. It wasn't until 1961, when Israel prosecuted Adolph Eichmann for war crimes, that many survivors revealed the extent of Nazi atrocities and Israel and the wider world truly listened to the testimonies. As tire details emerged, the concentration camp experience took on a named identity. Israelis adapted the term shoah, "destruction," to specifically mean the murder of the Jews. Elsewhere people used Holocaust, from the Greek term for burnt offering.

'"The jewish Holocaust' is such a disturbing phrase. It takes the emphasis off Germans and murder," Goldman states. "It suggests that history or God gave up the Jews for sacrifice." Moreover, he takes issue with the term's implication that murder victims willingly gave them selves up. Noting that many Jews resisted as best they could, he emphasizes instead the ways Jews have used their religious tradition to frame their understanding of the genocide. "The traditional Jewish response to hardship and misery is communal prayer for divine mercy," he says. Jews have long reacted to a history of disasters—especially the destruction of the ancient Temples in Jerusalem and the expulsion ofjews from Spain in 1492—with mourning and prayers that keep memories alive and shape responses to new catastrophes. This theme emerges, for example, in the testimony of concentration-camp survivor Leon Sperling, videotaped by the Fortunoff Holocaust Archive at Yale. Sperling describes seeing old men facing a Nazi firing squad. They wrapped themselves in prayer shawls and prayed vidui ha-gadol, the traditional last confession before death. They died sanctifying the name of God, Sperling says, referring to a tenth-century tragedy remembered in the Yom Kippur liturgy.

Indeed, it is part of the Jewish tradition to not forget. And it is part of the tradition to avenge tragedy by living the Jewish life numerous enemies have tried to destroy over the centuries. But as the Holocaust is memorialized in museums in this country, Israel, and at the sites of former concentration camps, questions of purpose remain. "What do you make of the claim that this is so these horrors won't happen again?" Goldman asked his class. His own view is clear. "I'm calling for a fascination with life instead of with murder."

In remembering theHolocaust andHiroshima, how is astelling as why.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePrince Chiming

June 1995 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Feature

FeatureAfter Eleven Commencing

June 1995 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Cover Story

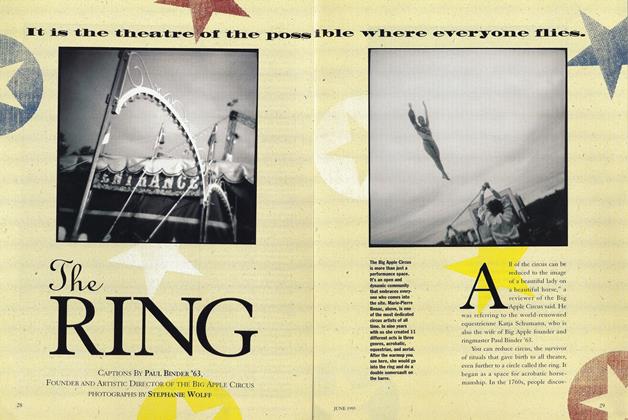

Cover StoryThe RING

June 1995 By Paul Binder '63 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

June 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

June 1995 By George M. Thompson Jr. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1960

June 1995 By Morton Kondracke

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleReligion Professor Ronald Green:

December 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorYou could say a woman started it all.

MARCH 1997 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleSports Illuminated

March 1998 By Karen Endicott -

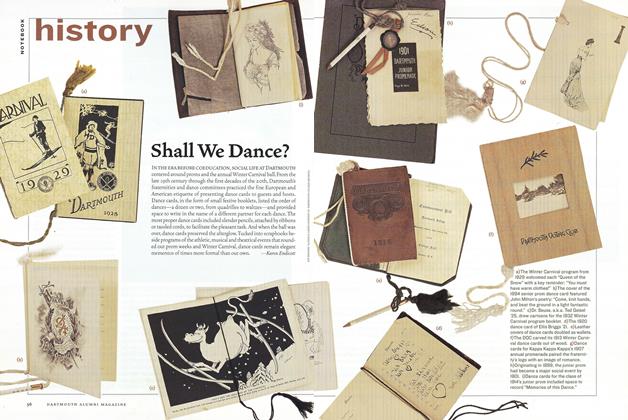

HISTORY

HISTORYShall We Dance?

Sept/Oct 2000 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWHEN POETRY SPEAKS

FEBRUARY 1991 By Professor Cleopatra Mathis, Karen Endicott

Article

-

Article

ArticleFELLOWSHIPS AVAILABLE FOR STUDY IN SCANDINAVIA

April 1920 -

Article

ArticleSenior Fellows Chosen

May 1935 -

Article

ArticleThe Origin of Palaeopitus

November 1941 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

January 1951 -

Article

ArticleBehind Every Grad, A Great Teacher

Sept/Oct 2007 -

Article

ArticleTHE HOVEYS

JANUARY, 1928 By Jason Almus Russell, 1920