The story about the 32-year-old senior who came in the back door and saved Baker's bells from a musical blackout.

Late Last July, The Biggest Thunderstorm of Summer hit Hanover. The wind gathered, sudden and stiff, and pounding rain steamed the hot asphalt. The storm rolled, furious, over the campus. Then CRACK, a sharp flash of light ripped through the rain, joining in a fierce electrical communion with Baker Library's clock tower. The 17 bells rang as one.

looked as if the bells might never ring again, at least without a whole new system. The bells did not play that afternoon, or the next day, or for weeks after. The lightning had fried the bells' computer system. There were no backups. No one at Dartmouth knew the outdated computer language that was used for the bells, or how the archaic wiring worked. It

And so it might have been, if one student had not taken his time before enrolling. If not for dyslexia, if Dartmouth Admissions had not rejected him twice before accenting him, James von Rittmann '95, the only man who proved able to fix the bells, would not have been here when he was most needed.

Which, frankly, would be fine for some people. There are those at Dartmouth who may not like hearing "The Lone Star of Texas" on the Hanover plain, or who somehow resent having Madonna's "Like a Virgin" accompany them on the way to a lecture on Milton.

This is a story about the student who brought the music back to a silent campus. It is a story also about a college dropout's struggle to get admitted to Dartmouth, his eventual work in garnering half a million dollars annually for the College, and his tragic loss of a yacht once owned by Al Capone.

The Ringer

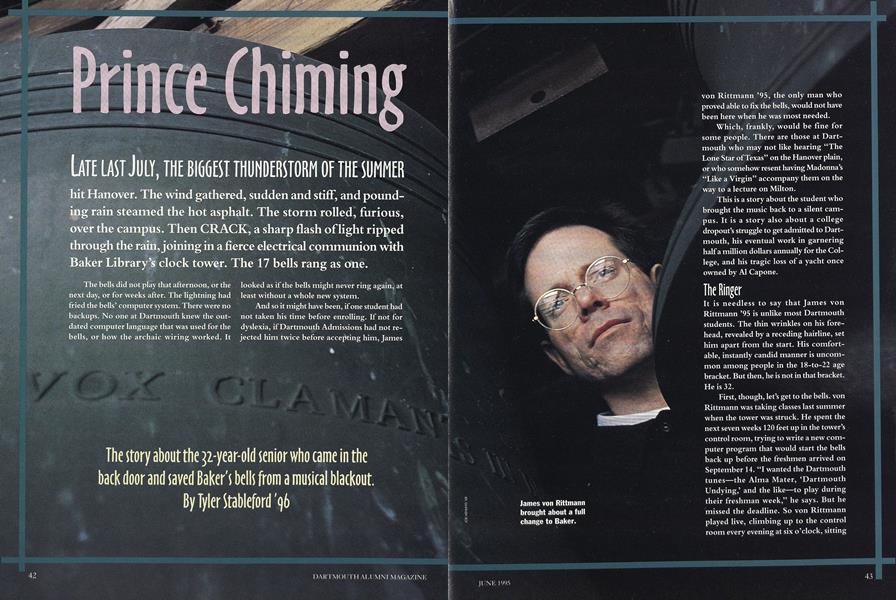

It is needless to say that James von Rittmann '95 is unlike most Dartmouth students. The thin wrinkles on his forehead, revealed by a receding hairline, set him apart from the start. His comfortable, instantly candid manner is uncommon among people in the 18-to-22 age bracket. But then, he is not in that bracket. He is 32.

First, though, let's get to the bells, von Rittmann was taking classes last summer when the tower was struck. He spent the next seven weeks 120 feet up in the tower's control room, trying to write a new computer program that would start the bells back up before the freshmen arrived on September 14. "I wanted the Dartmouth tunes—the Alma Mater, 'Dartmouth Undying,' and the like—to play during their freshman week," he says. But he missed the deadline. So von Rittmann played live, climbing up to the control room every evening at six o'clock, sitting down to a keyboard connected to the bell system, and playing a Dartmouth song. He did this until October 11, when the computer program was complete. The bells still ring daily at six o'clock, but the repertoire is now more diverse. "I try to have theme days," says von Rittmann. "For the class-change times I might play a number of Beatles songs, or songs from TV shows, or Madonna. Unfortunately, the bells can't play 'Jingle Bells'. They can't play a song where one note is repeated quickly like that." A campus favorite: "Ding Dong the Witch is Dead" from The Wizard of Oz. Students hum it into their next class.

The Bells

The tower's carillon is the second largest in the east, after the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. The sound travels amazingly, piercing through the silence of the Tower Room, and your body almost vibrates. You can hear the Baker bells while paddling a canoe below the Ledyard Bridge. You can hear them all the way up on Oak Hill near Storrs Pond. Sometimes, if the wind is right, you can catch the barest hint of a tune out by Dan & Whit's store in Norwich. The bells have become such a standard part of the Dartmouth day that they are sometimes hardly noticed until they are not heard.

There have been bells at Dartmouth for a long time. The first one was installed in Dartmouth Hall in 1781. As a means of signaling class and prayer times, it was an improvement over the conch horns students used to blow. The bell eliminated the annual 33-cent hornblowing fee assessed all students on top of tuition. The College's first carillonneur was Ozias Silsby, after whom Silsby Hall is named. He was paid to ring the bell every hour.

When Baker Library was constructed in 1928, an anonymous alumnus donated $40,000 for the purchase of 16 bells to fill the tower. A seventeenth was added in 1981 through the donation of Donal Morse '51.

In 1929 Walter Durrschmidt in the Music Department designed an instrument to save the carillonneurs the exhausting climb up the tower's 14 flights to ring the bells each hour. Durrschmidt connected a clock to a machine that read hole-punched paper scrolls much as a player piano does. Every morning, a carillonneur would feed a 30-foot scroll with punched holes into the machine, which read the punches and sent an electronic signal to the appropriate bell's hammer.

The Durrschmidt machine worked so well that Yale University bought and installed one in its own bell tower. Over the decades, though, the machine in Baker became temperamental, and it took constant work to punch holes in new scrolls when the old ones wore out. In 1979 Paul Grassie '80 and Chris Walker '73 designed a computer program that enabled the computer to read special music notation and control the operation of the bells. Songs could be programmed into the computer by entering the various notes to be played in sequence. The computer's internal clock would start a tune at the desired hour and minute—until that one fateful lightning stroke last July, which juiced the computer and its 15-year-old program and sent it to electronic oblivion.

But let's get back to James von Rittmann.

The Ringer

At the age of 19, frustrated with his studies, he dropped out of California's Mt. San Antonio College, von Rittmann (he insists that the "v" should never be capitalized) first saw Dartmouth in January 1988. "I drove up from Boston in a huge snowstorm," he says. "From the first time I saw the Green and the buildings, I knew. I knew that was where I wanted to be, where I was going to be." Admissions, however, did not agree. Not at first.

But he refused to be turned away from Dartmouth. So he came in through the back door, von Rittmann entered Babson College in Massachusetts and began linking one exchange program to another. The next term, he worked an exchange with Wellesley College "I knew they wouldn't let me actually attend, because I am a male, but they had another exchange program with Vassar." So he studied at Vassar for a term. Vassar had an exchange program with Dartmouth. The next term von Rittmann was in Hanover as a visiting student. "I knew once I got to Dartmouth I would be able to prove myself, that I could get accepted permanently."

At Dartmouth he was discovered to be dyslexic. "Dartmouth has one of the best programs for dyslexia in the country," von Rittmann asserts. "It's amazing how my academic ability has changed since I started dealing with my dyslexia. Until recently I never thought I could be a decent student." Armed with new study techniques—such as using a tape recorder for note-taking—von Rittmann saw his grades shoot up to a 3.8 average. He petitioned for permanent acceptance at Dartmouth. It was his third time applying. Applicants are allowed only three chances. On his final try, Admissions opened its doors.

The Fundraiser

Once admitted, von Rittmann needed a work-study job to help with his financial-aid loan. He joined the Green Corps campaign as a caller. Green Corps is the Alumni Fund's telemarketing fundraiser, employing students to telephone graduates for donations. One year after von Rittmann started at Green Corp$, the director graduated.

"I wanted that job," says von Rittmann. "I had been a caller for a year; I listened and knew why some of the alumni weren't giving money, and I thought Green Corp$ could respond to them more effectively."

He applied to be the program's student coordinator. The Alumni Fund gave him a shot.

von Rittmann wrote a manual of responses to alumni excuses, and started a new computer program to oversee record-keeping. "What I really had to do, though," he says, "was motivate the callers.'' He designed a number of games to blend in with the work each night. Now, callers compete in group games, from Hangman to Chutes & Ladders. Each successful call moves the caller closer to winning that night's prize: a gift certificate for dinner or to the Dartmouth Bookstore, or a weekend in Nantucket.

"The truth is, we have fun at work, and we raise a heck of a lot of money," says von Rittmann. Within one year, Green Corps income rose from $350,000 to more than $500,000.

The Boat

What follows admittedly sounds far-fetched. Skeptical readers have every reason for refusing to believe it—unless they have caught a glimpse of von Rittmann on television shows like "The Morning Show" with Regis Philbin. von Rittmann still has the videotapes. Beyond that, ifyou talk to von Rittmann himself, there is the look of fondness in his eyes, the way he hunches over in his seat and drops his voice, pulling you in closer, like Coleridge's ancient mariner drawing the wedding guest into his confession. If it is a tall tale, it is told convincingly. And then there are the videotapes.

It was Independence Day, 1986. Aircraft carriers, cruise ships and yachts funneled into the Hudson River, crowding around the Statue of Liberty for her 1OOth-anniversary celebration. In the bottleneck traffic, several yachts were damaged in collisions with other boats. One of them was the Liberty, a glamorous charter yacht once owned by Al Capone. The boat was towed to a dock for repairs, while the owner lost all his clients and revenue for the week. Encumbered with extraordinary debt, the boat was placed on the market.

"The owner was in big trouble. The banks were going to seize his house if he did not make payments by the next month," says von Rittmann. "So I said, 'Look, I can turn that boat around and pay off your debt, but I don't have the credit to put up for the loan. If you're willing to trust me, to hold the loan, I'll make sure you don't lose your house.'"

In what von Rittmann calls a stroke of luck, the owner turned the Liberty over to him. "Then what I had to do was make that boat an image, an image of prestige and regality." von Rittmann changed the boat's name to the Americana and anchored it just outside Manhattan's piers, never docking it. "And anytime I went ashore, I wore a crew uniform. People started noticing this elusive, beautiful yacht off shore, and began to wonder who the owner was. Who would believe he was only 25?"

Manhattan took his bait, von Rittmann's 140-foot boat became the most famous yacht in New York. Louis Gossett Jr., the Ford Foundation, and Ralph Lauren, among others, held their parties on the Americana. Ten months after he bought the boat, von Rittmann was offered $2.2 million for the business. He turned the offer down. "I wouldn't have sold my boat for the world," says von Rittmann. "It may not have been the best decision, but at that point in my life my boat was the pride of my life."

That winter von Rittmann and his crew sailed the Americana south to Florida and the Caribbean. He had almost completely paid off his debt for the purchase. But when the previous owner saw how successful von Rittmann had made his old business, natural jealousy turned hostile.

On a clear December morning on Fishers Island off the tip of Miami, the former owner boarded the Americana unannounced. He forced everyone off the boat and, according to von Rittmann, stole it. "He was dignified," says von Rittmann. "But it was violent. He forced us off with a gun." By the time von Rittmann could contact the authorities the Americana had disappeared. "Every personal belonging of mine was on that boat," says von Rittmann, "from artwork to my silverware, in addition to a safe full of cash. I have never loathed anyone as much as him."

For weeks, von Rittmann waited in Florida, hoping to hear that his boat had been recovered. The call never came.

Well, it did, actually, but not until eight months later. The good news was, the boat had been found in Fort Lauderdale. The bad news came when von Rittmann arrived at the harbor, where the Coast Guard had recovered the much-abused boat and chained it to the dock. "It was stripped to the bone, ransacked. Everything was gone.

"The hardest thing I have ever done was convincing myself that my boat business was over," says von Rittmann. "I had to let go, to move on. And it wasn't easy. I couldn't even afford the legal fees to sue the guy."

Soon after, von Rittmann determined to go back to school.

But let's get back to the bells.

The Bells

von Rittmann has now linked the belltower computer to his own Macintosh in 307 Wheeler Hall. Some may find it strange to see a 32-year-old man inhabiting a college dorm room. But von Rittmann says the dorms are where he is happiest. "I lived off campus my first year here, but I found that I wasn't meeting many of the students in my class. And I didn't want to go through Dartmouth without connecting with the kids here. So I'm in a dorm room, at the expense of some wall-shaking Pearl Jam booming from next door at 1 a.m. once in a while."

So why has von Rittmann devoted so much attention to the bells? "I didn't intend to, he admits. "I had no idea it would turn out to be such a commitment. And it would not have been had the tower not gone down in the storm. But it really means a lot to me that the College lets a student run the bells.

Most people don't go wild thinking about bells and I don't either, for that matter, he says. But the bells are one of those things that are a given at Dartmouth."

Commencement

On Homecoming Night, von Rittmann played live on the bells as the bonfire flamed. On Christmas Eve, "Silent Night" rang out at midnight.

To make sure someone is left in con- trol after he graduates, von Rittmann has taken an apprentice, Jennifer Herbst '96, to pass on knowledge of the controls.

And then, on Sunday, June 11, von Rittmann will receive his diploma—in Memorial Stadium, unfortunately. Back at Baker, the bells will play "Pomp and Circumstance," "Dartmouth Undying," and the Alma Mater. He will be in the simultaneous position of performer and audience, as he has been fundraiser and beneficiary, student and teacher.

von Kittmann knows how to play both sides.

James von Rittmannbrought about a fullchange to Baker.

Regis's Beat James made Bachelor of the Year and hit the talk shows. Here Regis Philbin schmoozes him up aboard his yacht.

Al Capone's Boat was stolen from von Rittmann at gunpoint.

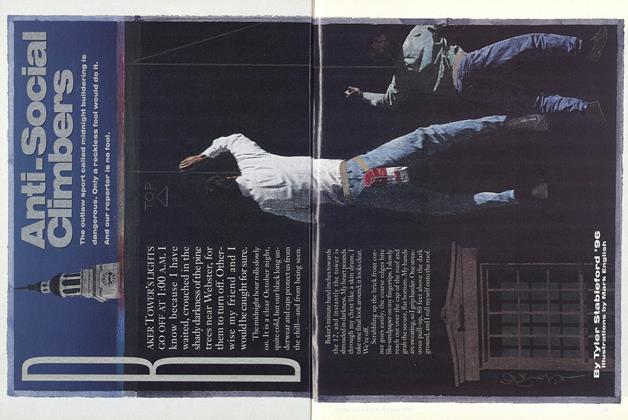

Tyler Stableford is a Whitney Campbell Undergraduate Intern with this magazine.His last feature story for us, "Anti-SocialClimbers, appeared in the Winter issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAfter Eleven Commencing

June 1995 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Cover Story

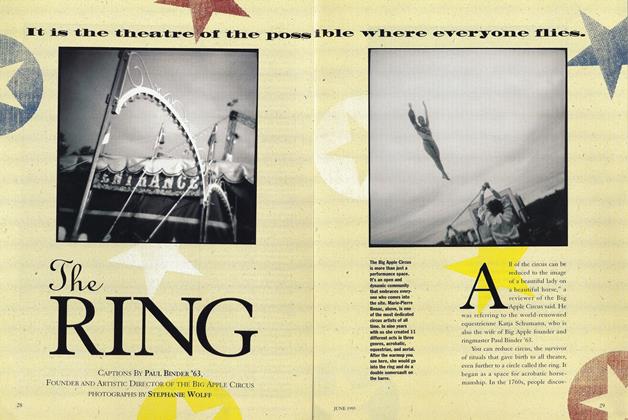

Cover StoryThe RING

June 1995 By Paul Binder '63 -

Article

ArticleMemory and Catastrophe

June 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

June 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

June 1995 By George M. Thompson Jr. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1960

June 1995 By Morton Kondracke

Tyler Stableford '96

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Sept/Oct 2006 -

Article

ArticleOkay, Now Bounce

November 1994 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Feature

FeatureAnti-Social Climbers

December 1994 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Article

ArticleOn June 23 choreographer Moses Pendleton '71

October 1995 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Cover Story

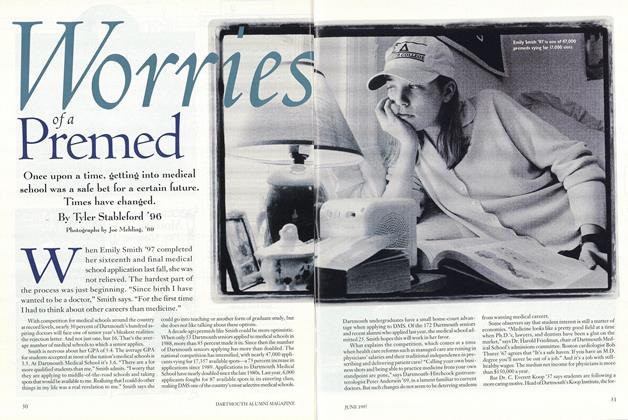

Cover StoryWorries of a Premed

JUNE 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Photography

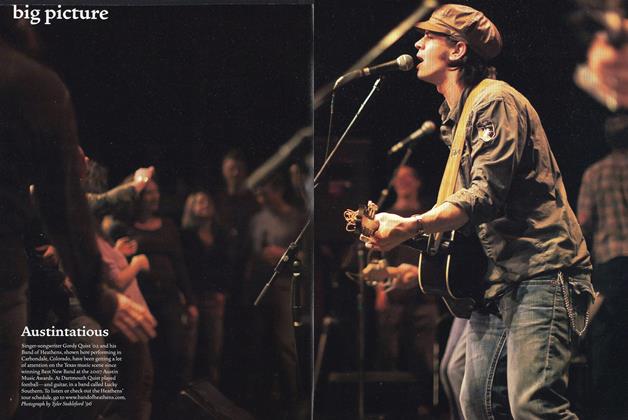

PhotographyBig Picture: Austintatious

Sept/Oct 2008 By Tyler Stableford '96

Features

-

Feature

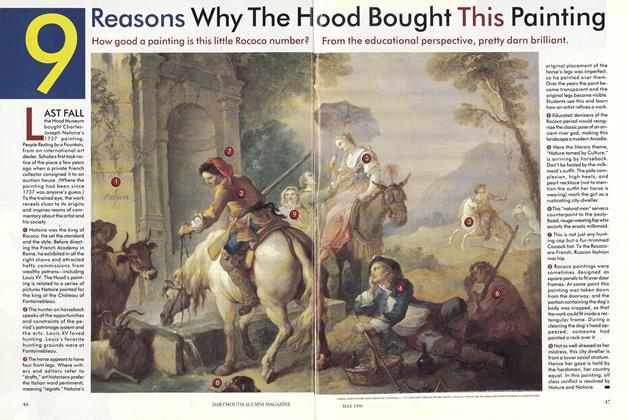

Feature9 Reasons Why the Hood Bought This Painting

MAY 1996 -

Feature

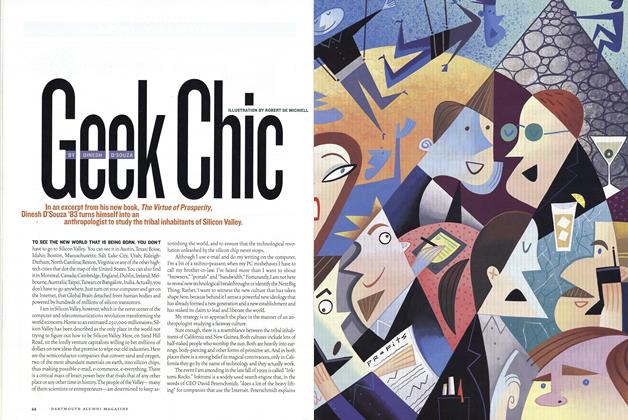

FeatureGeek Chic

Jan/Feb 2001 By DINESH D'SOUZA -

Feature

FeatureJames Marsh, Dartmouth, and American Transcendentalism

MARCH 1969 By Douglas M. Greenwood '66 -

Feature

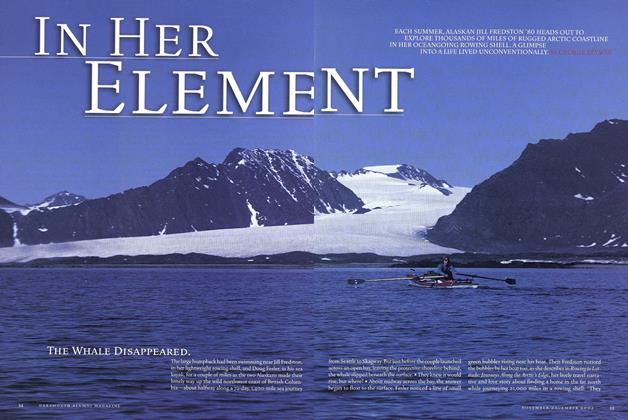

FeatureIn Her Element

Nov/Dec 2002 By GEORGE BRYSON -

FEATURE

FEATURESibling Revelry

MARCH | APRIL 2020 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureThe Dinan Decade

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham