AUTHOR JACQUES STEINBERG POSES the keynote question, "Should our federal museum contain history or iconography?" ("The Bomb in the Nation's Attic," May). But he seems (along with others quoted in the article) to have ignored the most obvious answer "Yes!"

The Enola Gay was powerful enough in 1945 to transport tons of ordnance and kilotons of explosive force; it should be powerful enough today to convey a broad diversity of ideas all valid, many disturbing, and some mutually contradictory.

Why should there not be multiple interpretations defining the Enola Gay as a "winged victory" symbol to those whose lives may have been saved by the aircraft's mission over Hiroshima, as an "angel of death" symbol to those who experienced the horror below, and as a symbol of anxiety and uncertainty to a world that has lived for five decades in the shadow of the mushroom cloud? Each of these truths is valid, and one does not refute or canqel the others.

HALLOWELL, MAINE

IT IS HARD TO IMAGINE THAT HARRY Truman, who personally saw war's realities in WW I, when he weighed his decision, thought only of the bomb's development cost, the far-reaching implications of the yet-to-be-named and engaged "Cold War," and the abstract figures fed to him of potential casualties from invading Japan.

It is hard to believe he ignored the dreadful human cost of ghastly battle on Okinawa, and did not extrapolate the far greater cost that lay ahead, for American soldiers, for Japanese soldiers, and for Japanese civilians.

Professor Sherwin's book no doubt appropriately calls attention to the horror of nuclear war, but his criticism of the Smithsonian's decision to cancel the Enola Gay exhibit is dulled by his inability to realize what kind of enemy the Japanese were, and his "historical" second guessing at what they might or might not have done.

SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO

THE TENDENTIOUS FLAVOR OF THE script is conveyed by this statement about the war in the Pacific: "For most Americans...it was a war of vengeance. For most Japanese it was a war to defend their unique culture against Western imperialism." Such rewriting of history while many of us who lived it are still around raises leftist political correctness to a new level of chutzpah and absurdity.

Recall that the Japanese launched a war of imperial conquest in 1937. Their atrocities in Korea and China were extraordinary slaughter of civilians, rape, torture, slave labor, and enforced prostitution. Then came "the day which shall live in infamy" and the Bataan death march. We went to war because we had to, and ended it with the bomb in preference to invading Japan at the cost of countless thousands of American lives (we had just suffered over 20,000 casualties taking the small atoll of Iwo Jima).

To have the Smithsonian's scholars (?) turn all this on its head and suggest we view the Japanese and their unique culture as victims of vengeful and racist American imperialism is almost breathtaking.

EAST DORSET, VERMONT

YOUR COVER STORY WITH THE Caption, "Smithsonian head Mike Heyman '51 discovers that some history won't fly," implies the editors agree with the revisionists. I am outraged!

Never forget who started the war. Your revisionists should also keep in mind that once the surrender was accomplished, never in the history of the world was a victor as magnanimous as the United States.

HARTLAND WISCONSIN

IF ONLY MARTIN SHERWIN HAD ASKED me I could have saved him and his colleagues the trouble of writing a 600-page "explanation" of why the U.S.A. dropped the bomb on Japan. The answer is short and simple: Japan surrendered five days later.

SHERMAN OAKS, CALIFORNIA

IN ALL THE ENDLESS SQUABBLING over the atomic bombing of Japan, one question remains in my mind:

Had Japan incinerated Toledo with one previously unheard of weapon, would we have unconditionally surrendered to Japan within only three days?

Isn't it obvious that it would have taken more than three days for us to even determine what had happened to Toledo? Why did we destroy another major population center after so short a time?

That second bombing was obscene.

WESTON, CONNECTICUT

WORKING IN A NAVAL HOSPITAL during WW II, I had the privilege of caring for naval and marine combatants. How well I remember the marine in continuous pain from his right arm that had been shattered by machine gun fire and the naval gunners' mate who lost a lower leg when a Kamikaze hit the aircraft carrier Ticonderoga. I will never forget the marine who had to listen to the piercing screams of his comrades who were being tortured at night by the Japanese on Gaudalcanal. Needless to say, I was upset with the Enola Gay exhibit planned for the Smithsonian. The exhibit allegedly suggested that the United States was unnecessarily aggressive and prejudiced against the Japanese. How many of the exhibit planners were in that war? How many were even born before the end of the war?

NEWPORT NEWS, VIRGINIA

AT THE TIME OF THE AUGUST 1945 A-bomb drop, already one of every 20 of my Dartmouth classmates had given his life in the war. Any additional casualties would have been even more tragic. I have no misgivings about my participation in the Manhattan Project at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, in 1944 and 1945.

1940 CLASS SECRETARY

Martin Sherwin '59 replies:

I NEVER SUGGESTED, AS HUGH Morris implies, that Truman thought "only of the bomb's development cost." The hope that the atomic bomb would end the war certainly motivated Truman to use it. However, there were other reasons related to domestic and postwar diplomacy that evidently led him and his top advisors to ignore other alternatives that might have brought the war to an even earlier conclusion. Secretary of War Henry Stimson notes in his memoirs: the possibility exists that "a clearer and earlier exposition of American willingness to retain the Emperor would have produced an earlier ending to the war."

Several letters correctly point out that an invasion of Japan would have been terrible and, therefore, that the atomic bombings were preferable. If those were the only two choices, I would have to agree. Those two choices were not the full range of choices. Modifying the disastrous doctrine of "Unconditional Surrender" to guarantee retention of the Emperor (which was done after both bombs were dropped), and waiting two days for the Soviets to enter the war against Japan, were other options. Truman and Stimson told the American public an abridged version of the truth.

In response to Alexander Hoffman's reference to the first draft of the Enola Gay exhibit script, the quotation was taken out of context by Air Force Magazine and then repeated by reporters and columnists. (The quotation was part of a more detailed version of his second paragraph.) I reviewed that script and it was my conclusion that it was too celebratory. The killing of more than 200,000 people at a time when the Japanese government had been seeking surrender terms for two months, is not something a great nation like the United States should celebrate.

Martin Sherwin ivho recently resigned asdirector of Dartmouth's Dickey Center, is theWalter S. Dickson Professor of History atTufts University.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

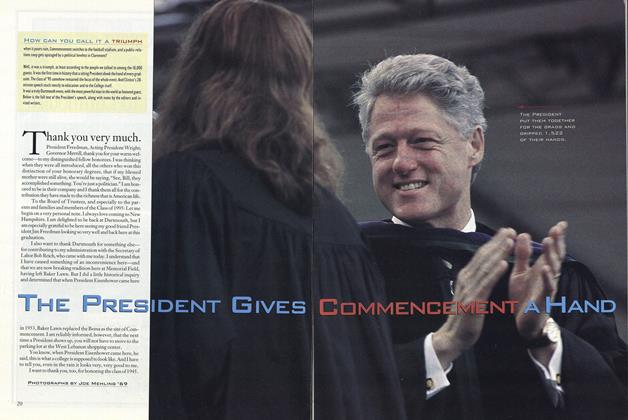

Cover StoryThe President Gives Commencement a Hand

September 1995 -

Feature

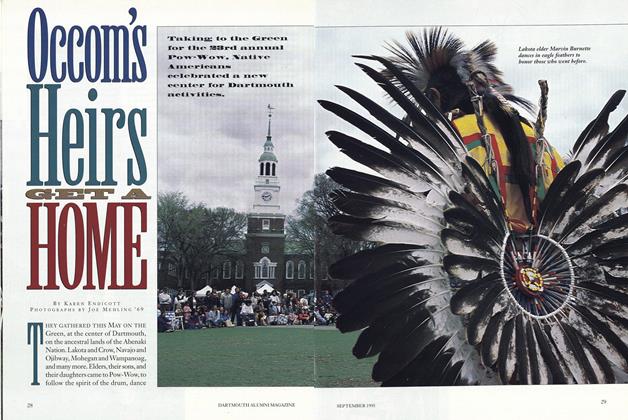

FeatureOccom's Heirs Get a Home

September 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

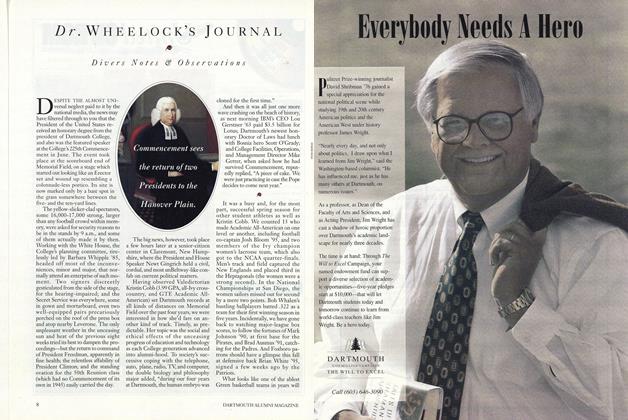

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

September 1995 By E. Wheelock -

Article

ArticleObligations of the Educated

September 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1989

September 1995 By Tom Avril -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

September 1995 By Daniel Zenkel, Michael Carothers,