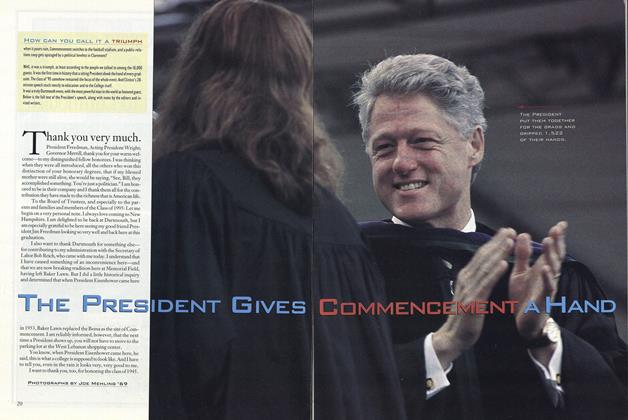

This month's Presidential Range presents the full text of President Freedman's speech at Dartmouth's 225 thCommencement.

After President Clinton's spirited and stirring address, few additional words are needed. Still, I make bold to add one thought, as I congratulate each of you on the achievements that have led to this happy ceremony.

One of President Clinton's predecessors in office, John Adams, who received an honorary degree from Dartmouth in 1782, once wrote in a letter to his wife, Abigail, "I must study politics and war that my sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. My sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history, naval architecture, navigation, commerce, and agriculture, in order to give their children a right to study painting, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain."

Adams thus recognized that education promised progress and greater privilege from generation to generation. As the members of one generation pursued the more practical sides of higher learning, they created opportunities for their children to devote their time to the classical pursuits of a cultured mind.

But what kind of obligations, we might ask, do such educational opportunities impose upon successive generations of children? The highest obligation of an educated person in a democracy is to be a citizen, a person devoted to the ideals of the nation and to the well-being of the entire commonwealth, rather than to only a narrow segment of it. And yet the achievement of that obligation is increasingly rare.

More than 200 years ago, Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote, "We have physicists, geometers, chemists, astronomers, poets, musicians, painters." But, he added, "we no longer have citizens." What Rousseau wrote about 18th-century France is ominously accurate about the United States today.

In die marketplace of political discourse, the steady trend toward the fragmentation of American life risks isolating each of us, causing us to speak past one another and turning us into special pleaders for our own preserves of privilege and economic interest.

The problem is not that the voices are too numerous, but that they are too demanding, parochial, self-serving, and unforgiving. They are too loud and yet too small. Too few of these voices are directed to the common good or focused upon the largest aims of the nation. Too few are devoted to creating that sense of community that enables a pluralistic nation to celebrate a common destiny.

Too much of our current political discourse is rancid and mean-spirited, displaying a common denominator of division division between races and nationalities, between young and old, between immigrant and native-born, between the affluent and the poor, between those who serve government and those who assert that they are oppressed by it. When divisions such as these are exploited for their short-term political potential, the ideals of citizenship are defamed.

At such a juncture in our history, we have good reason to ask: Who speaks for those Americans who lack political clout? Who are disadvantaged? Who are children of poverty and of immigration? Who do not have the opportunities that higher education has conferred upon fortunate people like you and me?

One of the reasons that Dartmouth Commencements are distinctively American occasions is that a liberal education seeks to prepare men and women for the responsibilities of democratic citizenship. At every Commencement exercise, we affirm our confidence that education, knowledge, and reason can improve the human condition. We assert our faith that our graduates have been well schooled to commit themselves to the attainment of a more perfect political and social order.

This is no idle commitment. Citizenship is an essential product of a liberal education. For want of such a civic commitment, societies forfeit the capacity to be humane and democratic.

This Commencement ceremony, then, is an exercise in American renewal an occasion for enlarging the number of citizens who are prepared to be leaders in binding this country together, establishing opportunity for the least of its citizens, and emphasizing the role of informed discussion of civility, self-discipline, tolerance, and trust—in determining the nation's future. Those whose minds have been deepened by a liberal education dare not pernit this country to be riven by the politics of difference.

I wish each of you every happiness and satisfaction in the years ahead. May your affection for "Dartmouth undying" be with you always. Congratulations and good luck!

Commencementis an exercise inAmerican renewal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe President Gives Commencement a Hand

September 1995 -

Feature

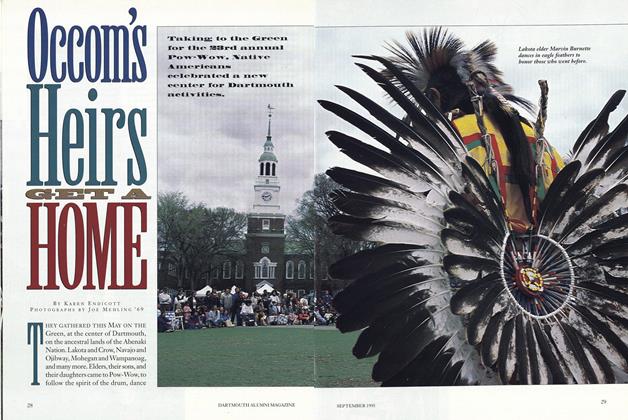

FeatureOccom's Heirs Get a Home

September 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

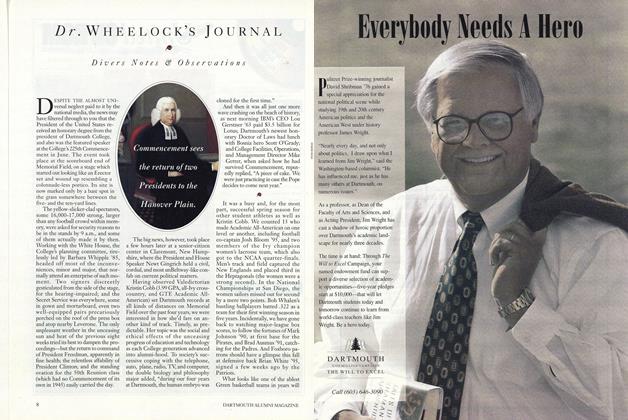

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

September 1995 By E. Wheelock -

Class Notes

Class Notes1989

September 1995 By Tom Avril -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

September 1995 By Daniel Zenkel, Michael Carothers, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

September 1995 By Brooks Clark

James O. Freedman

-

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleTHE HEROIC OUTSIDER

December 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Time Allotted Us

June 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWhen Knowledge Cures

October 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA Quiet Greatness

DECEMBER 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Uncertain Future of Medical Education

DECEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman