You belong where land and soul merge.

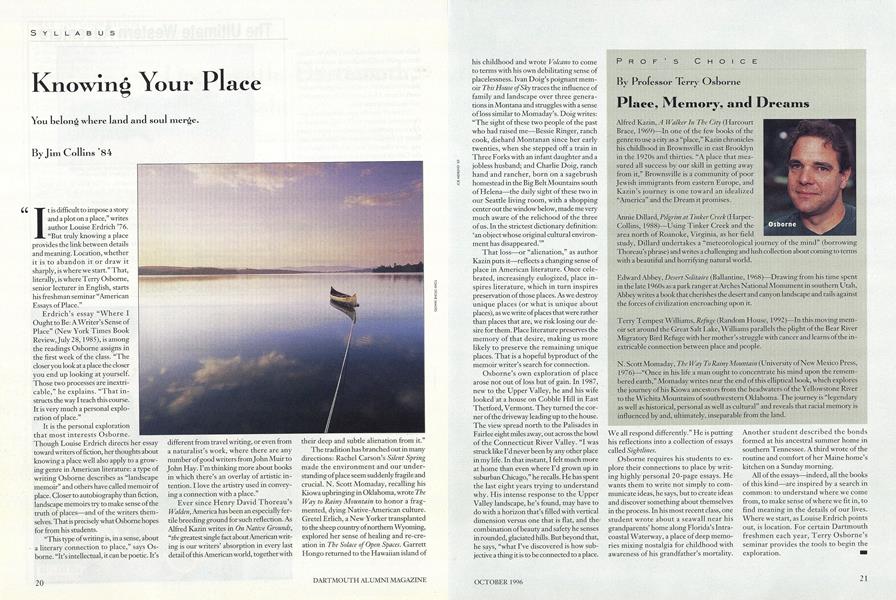

"It is difficult to impose a story and a plot on a place," writes author Louise Erdrich '76. "But truly knowing a place provides the link between details and meaning. Location, whether it is to abandon it or draw it sharply, is where we start." That, literally, is where Terry Osborne, senior lecturer in English, starts his freshman seminar "American Essays of Place."

Erdrich's essay "Where I Ought to Be: A Writer's Sense of Place" (New York Times Book Review, July 28, 1985), is among the readings Osborne assigns in the first week of the class. "The closer you look at a place the closer you end up looking at yourself. Those two processes are inextricable," he explains. "That instructs the way I teach this course. It is very much a personal exploration of place."

It is the personal exploration that most interests Osborne. Though Louise Erdrich directs her essay toward writers of fiction, her thoughts about knowing a place well also apply to a growing genre in American literature: a type of writing Osborne describes as "landscape memoir" and others have called memoir of place. Closer to autobiography than fiction, landscape memoirs try to make sense of the truth of places—and of the writers themselves. That is precisely what Osborne hopes for from his students.

"This type of writing is, in a sense, about a literary connection to place," says Osborne. "It's intellectual, it can be poetic. It's different from travel writing, or even from a naturalist's work, where there are any number of good writers from John Muir to John Hay. I'm thinking more about books in which there's an overlay of artistic intention. I love die artistry used in conveying a connection with a place."

Ever since Henry David Thoreau's Walden, America has been an especially fertile breeding ground for such reflection. As Alfred Kazin writes in On Native Grounds, "the greatest single fact about American writing is our writers' absorption in every last detail of this American world, together with their deep and subtle alienation from it."

The tradition has branched out in many directions: Rachel Carson's Silent Spring made the environment and our understanding of place seem suddenly fragile and crucial. N. Scott Momaday, recalling his Kiowa upbringing in Oklahoma, wrote TheWay to Rainy Mountain to honor a fragmented, dying Native-American culture. Gretel Erlich, a New Yorker transplanted to the sheep country of northern Wyoming, explored her sense of healing and re-creation in The Solace of Open Spaces. Garrett Hongo returned to the Hawaiian island of his childhood and wrote Volcano to come to terms with his own debilitating sense of placelessness. Ivan Doig's poignant memoir This House of Sky traces the influence of family and landscape over three generations in Montana and straggles with a sense of loss similar to Momaday's. Doig writes: "The sight of these two people of the past who had raised me—Bessie Ringer, ranch cook, diehard Montanan since her early twenties, when she stepped off a train in Three Forks with an infant daughter and a jobless husband; and Charlie Doig, ranch hand and rancher, born on a sagebrush homestead in the Big Belt Mountains south of Helena—the daily sight of these two in our Seattle living room, with a shopping center out the window below, made me very much aware of the relichood of the three of us. In the strictest dictionary definition: 'an object whose original cultural environment has disappeared.'"

That loss—or "alienation," as author Kazin puts it—reflects a changing sense of place in American literature. Once celebrated, increasingly eulogized, place inspires literature, which in turn inspires preservation of those places. As we destroy unique places (or what is unique about places), as we write of places that were rather than places that are, we risk losing our desire for them. Place literature preserves the memory of that desire, making us more likely to preserve the remaining unique places. That is a hopeful byproduct of the memoir writer's search for connection.

Osborne's own exploration of place arose not out of loss but of gain. In 1987, new to the Upper Valley, he and his wife looked at a house on Cobble Hill in East Thetford, Vermont. They turned the corner of the driveway leading up to the house. The view spread north to the Palisades in Fairlee eight miles away, out across the bowl of the Connecticut River Valley. "I was struck like I'd never been by any other place in my life. In that instant, I felt much more at home than even where I'd grown up in suburban Chicago," he recalls. He has spent the last eight years trying to understand why. His intense response to the Upper Valley landscape, he's found, may have to do with a horizon that's filled with vertical dimension versus one that is flat, and the combination of beauty and safety he senses in rounded, glaciated hills. But beyond that, he says, "what I've discovered is how subjective a thing it is to be connected to a place. We all respond differently." He is putting his reflections into a collection of essays called Sightlines.

Osborne requires his students to explore their connections to place by writing highly personal 20-page essays. He wants them to write not simply to communicate ideas, he says, but to create ideas and discover something about themselves in the process. In his most recent class, one student wrote about a seawall near his grandparents' home along Florida's Intracoastal Waterway, a place of deep memo- ries mixing nostalgia for childhood with awareness of his grandfather's mortality. Another student described the bonds formed at his ancestral summer home in southern Tennessee. A third wrote of the routine and comfort of her Maine home's kitchen on a Sunday morning.

All of the essays—indeed, all the books of this kind—are inspired by a search in common: to understand where we come from, to make sense of where we fit in, to find meaning in the details of our lives. Where we start, as Louise Erdrich points out, is location. For certain Dartmouth freshmen each year, Terry Osborne's seminar provides the tools to begin the exploration.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

October 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureNaming the Animals

October 1996 By Robert Pack '51 -

Feature

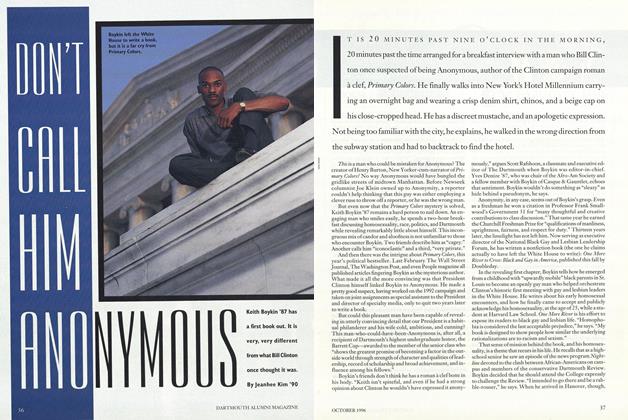

FeatureDON'T CALL HIM ANONYMOUS

October 1996 By Jeanhee Kim '9O -

Cover Story

Cover StorySecond Nature

October 1996 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

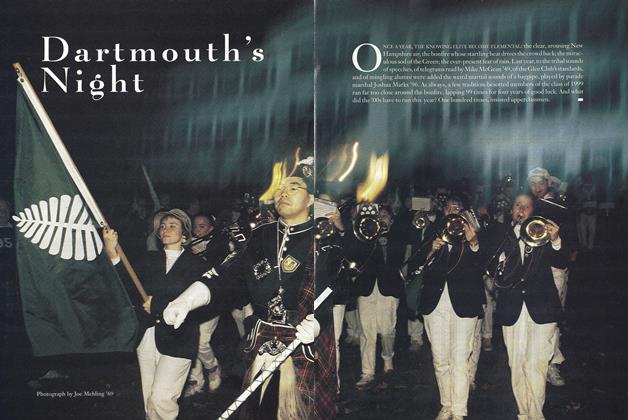

FeatureDartmouth's Night

October 1996 -

Article

ArticleThe Orange on Campus Is Not on Leaves

October 1996 By "E. Wheelock"

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH CLUB ORGANIZED IN BRIDGEPORT, CONNECTICUT

April, 1923 -

Article

ArticleThey Threw Back 14-Pounders

November 1950 -

Article

ArticleRave Reviews?

APRIL 1986 By Dorothy L. Foley '86 -

Article

ArticleNotebook

July/Aug 2010 By NICK WIEBE -

Article

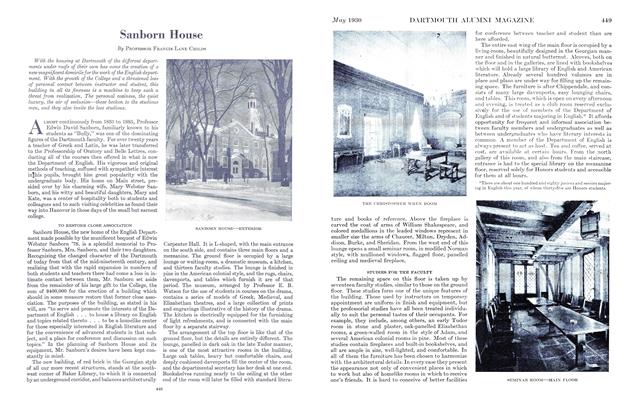

ArticleSanborn House

MAY 1930 By Professor Francis Lane Childs -

Article

ArticleINTERESTING LETTER FROM SECOND OLDEST ALUMNUS

June, 1923 By S. H. JACKMAN.