The class of 2000 is an extremely talented and interesting group of young people who are, judging by their abilities and character, more than equal to the challenges they will face in the next century. Beyond their demonstrated abilities, the class of 2000 represents the changing demography of America and the world. They come from 47 of the 50 United States and 20 foreign countries. Nineteen percent come from minority backgrounds. The representation of women and men is virtually equal, as it has been for the last three years. Interestingly, there are 45 alumni daughters and 38 alumni sons. Perhaps anticipating the demands of the next century, the majority of first-year students state a preference for science and technology concentrations. Two thirds of the class attended public secondary schools. And 47 percent of the class is receiving some form of need-based financial aid, including $6.9 million in scholarships. The class of 2000 also includes a sled dog racer, a professional square dance caller, several performing clowns, a Bosnian refugee, the great, great grandson of Daniel Boone, a direct descendent of Samson Occom, a student of Tibetan heritage, and three sets of twins. Twenty-six percent were varsity team captains in high school, 24 percent were seriously involved in music, 15 percent performed community service on a regular basis, nine percent were newspaper editors, eight percent were class presidents, and 17 percent worked at a job at least ten hours a week. The makeup of this group is a far cry from the classes attending selective colleges a generation—let alone a century—ago.

One of the first major challenges these students faced on their way to the next millennium was the college admissions process itself—one that is far more complex and competitive than it was a generation ago. Selecting a college has always been a challenge for students as they take stock of their previous accomplishments and try to define their goals for the future. Today's students move through this transition from adolescence to adulthood in the context of a national mania about selective admissions. No longer is the search for a college left to the private ruminations of the student and conversations with family members and trusted advisors. Contemporary culture seems fixated on the college admissions process. We are constantly reminded of its importance by a barrage of television, radio, newspaper, and magazine stories.

Anxiety about getting into the "right college" has also spawned an industry of services from college guides and consultants to test preparation and college financial planning. All of a sudden everybody is an expert on an activity that is highly individualized and personal for each student and incredibly complex and subtle for the colleges as they recruit and select students.

No dean of admissions in the 1990s can escape the fact that the public, and the media, is quick to analyze, and criticize, what it thinks are the admissions policies and priorities of colleges and universities. Admissions issues are frequently debated in the political arena and, increasingly, the courts are being called upon to rule on admissions-related cases. Admissions policies and decisions have become a vehicle for working out important national social issues. Witness the debate about affirmative action and various notions of merit. Moreover, questions abound about student access to higher education and its relationship to the cost of education. Admissions policies and decisions give action to the values of an institution and as such are subject to considerable public scrutiny. Because education contributes so significantly to economic advantage in American society, various constituencies have a keen interest in trying to influence the policies that determine who has access to higher education. In the case of elite, highly selective colleges like Dartmouth the stakes are particularly high because the quality of the education and future benefits are so considerable.

There is little doubt that the national focus on selective admissions has given Dartmouth greater national visibility. The effort to attract the most talented students to Hanover takes place in a keenly competitive national market. Dartmouth now competes for the talented high school seniors, most directly with other elite, private universities. However alumni or others see us, prospective students see us as more closely associated with these universities than selective liberal arts colleges.

Because success in enrolling an outstanding class is highly dependent on the size and quality of the applicant pool, selective colleges and universities are engaged in much more aggressive recruiting. Potential members of the class of 2000 were inundated with information about numerous colleges from die time they were sophomores and juniors in high school. At Dartmouth our recruiting takes four major forms:

•Trips by admission officers around the country, and world, to meet prospective students.

•Sophisticated publications, including direct-mail efforts, that seek to distinguish Dartmouth from the competition.

•Campus visit programs such as tours, interviews, and overnights that bring prospective students to Hanover.

•Alumni recruiting and interviewing at the local level, which expands our reach.

Increasingly, the computer and the World Wide Web are a means by which colleges convey information to prospective students. But the most influential form of recruitment, I think, is the campus visit. There is no substitute for seeing Dartmouth firsthand.

All of these efforts seem to be working. The sorting process engaged by both the colleges and the students, referred to by some as the "great admissions funnel," generates a considerable amount of contact between prospective students and the College. For the class of 2000, more than 63,000 students contacted our office for information about applying. Tens of thousands of students and their families visited Hanover to see the campus firsthand. Admissions staff members visited 735 secondary schools around the United States and overseas. The admissions staff conducted 2,355 personal interviews on-campus while alumni conducted another 7,394 interviews in their home areas. Ultimately, Dartmouth received 11,398 applications,"an all-time record. From this group of candidates 2,271 were offered admission, making it the most competitive admissions year in Dartmouth's history. The class of 2 000 numbered 1,095 students when it enrolled in September.

The review of applications for admission is a thorough and painstaking process that lasts for four months. Inevitably it involves many hard choices. Imagine, for a moment, 11,398 applications sitting in the admissions office, each one containing: a student biographical information form, lists of activities and interests, three short and one long essay, a high school transcript, SAT I and SAT II (formerly achievement) test scores, guidance-counselor recommendation, two teacher recommendations, a peer reference, and an interview evaluation. And, yes, we do receive scores of videotapes, photographs, poems, brownies, and helium balloons. All of the materials submitted by, and on behalf, of more than 11,000 applicants are carefully evaluated by at least two, and in most cases three, different admissions officers. Each reader is responsible for writing a short summary outlining the strengths and weaknesses of the applicant and recommending a final decision. As an application folder moves through the evaluation process, officers do not see the summary and recommendation of the previous readers.

Our reading of applications is not only thorough; it seeks also to be both objective and humane. With more than 11,000 well qualified applicants there is little room for subjectivity. Readers assign academic and personal ratings, based on historical data for the last four classes admitted to Dartmouth. After the reading of applications, and the sorting out of exceptionally strong and noncompetitive candidates, the remaining applications are considered by a committee of three or four officers who debate each candidate and reach a final decision. This is a deliberate and considered process, with a number of checks and balances and a strong analytical base. Unfortunately for some candidates, chocolate-chip cookies don't make a difference.

As important as the selection process is, the criteria for selection are even more so. Obviously, the first and highest priority for admission is the academic accomplishment and intellectual quality of the student. These are measured by both tangible and intangible factors. Included in the tangibles are test scores, rank in class, and grade-point average. Academic judgments must also consider the quality of high school programs undertaken by the student, patterns and trends in grade performance, and the relationship of different academic measures to one another. We are careful not to overlook students with highly developed but more specialized academic talents; students with exceptional abilities in one area can sometimes be overlooked in a selection process that averages out talent or looks for uniformity in performance. But it is the presence of the intangible measures of academic accomplishment, promise, and dedication that really distinguish the exceptional applicants from the "solid" ones. The exceptional applicants are typically admitted; the others are most often denied admission.

The key difference between the two groups is intellectual curiosity. This quality eludes precise measurement, but we always look for it. Academic "stretch," intrinsic interest in learning, excitement about ideas, a questioning attitude, involvement in discussions, breadth of view, interdisciplinary thinking, tolerance for new and different ideas, and risk taking are all qualities that signal intellectual curiosity. We seek critical thinkers with the independence of mind and personal confidence to assert their ideas.

Excellence in extracurricular areas also receives careful attention. Dartmouth is fortunate to have a large number of applicants who demonstrate both academic and extracurricular distinction. We seek evidence of accomplishment and commitment. Leadership, developed talents in the arts and athletics, significant commitments to school activities, community service, and parttime jobs are all noteworthy examples. What is important is the depth of commitment and follow-through that lead to significant contributions and recognition from others. There is an intangible dimension to extracurricular records, and we must be attuned to those human qualities—integrity, leadership, compassion, open-mindedness, sense of humor, independence, energy—that will continue to improve the Dartmouth community.

I believe our admissions process does attract and enroll some of the finest young people from around the world, and the statistics certainly bear that out. But, as you can see, the first-year class is much more than its aggregate statistics; it is a collection of fascinating and talented individuals. At Dartmouth we talk as much as ever about educating the "leaders of tomorrow." Leadership embraces both intellectual and human dimensions. The ability to influence people and events with the quality and conviction of one's ideas has always been a significant facet of leadership. This is likely to be even more important in the next millennium. If the members of the class of 2000 use the impressive resources of Dartmouth to develop their considerable talents, their effect on the next century will be awesome.

Dartmouth's admissions dean, Karl Furstenberg, explainsbow the class of zooo got here, and where it's likely to go.

"The idea of social responsibility is the very seam that holdssociety together. The social contract keeps the human race on its feet. It is thissocial and moral responsibility that keeps us from turning on our brothersand turning tomorrow into a nuclear judgment day." From the essay of an applicant to the class of 2000

Karl Furstenburg likes to call himselfDartmouth's "vice president of sales." Salesare up: applications to Dartmouth have risen40 percent in the last five years. A HarvardM.B.A., Furstenberg came to the College in1990 and was made a VP in 1992.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCue the Millennium

November 1996 -

Feature

FeatureA Billion Dollars

November 1996 By Rebecca Bailey -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOught Ought

November 1996 By Joe Mehling '69 -

Article

ArticleWhat Beethoven Heard

November 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleA Two-for-One- Convocation and the Med School's 200th

November 1996 By E. Wheelock -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty's Turn to Give

November 1996 By Noel Perrin

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1973 -

Feature

FeatureThe Philosophy of Culture

DECEMBER 1966 By ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32 -

Feature

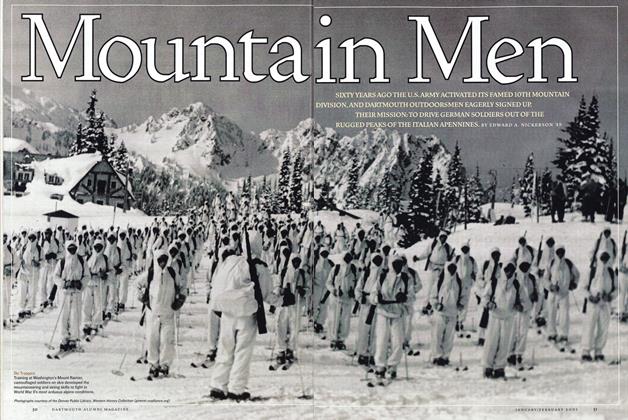

FeatureMountain Men

Jan/Feb 2001 By EDWARD A. NICKERSON ’49 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Mar/Apr 2012 By JOSEPH MEHLING '69 -

Cover Story

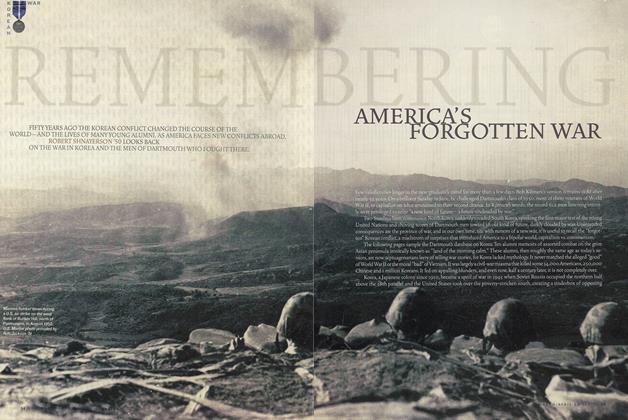

Cover StoryRemembering America’s Forgotten War

Mar/Apr 2003 By ROBERT SHNAYERSON ’50 -

Feature

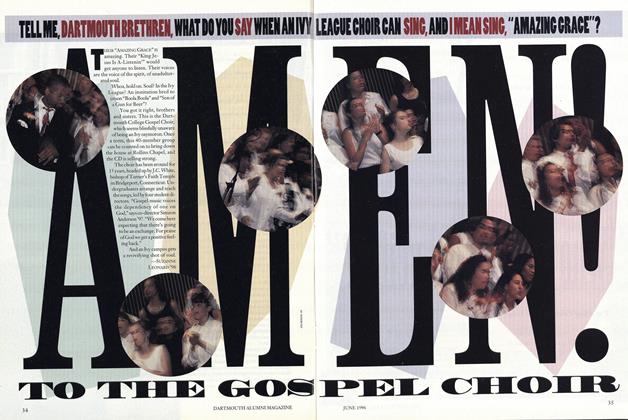

FeatureAMEN! TO THE GOSPEL CHOIR

JUNE 1996 By Suzanne Leonard ’96