Adventurer Ned Gillette '67 and his wife, Susie Patterson, both former U.S. Olympian she a cross-country skier, she a downhiller were shot by robbers on August 5 while camping in northern Pakistan. Gillette was killed in the attack, having been hit twice in the stomach and once in the back. Even as he was dying, he urged his wife to flee. Patterson, the sister of Dartmouth ski coach Ruff Patterson, was shot in the back. She recovered from her wounds in a hospital in Islamabad, and has returned tO the U.S.

Robert Sullivan '75 wrote about the couple for this magazine in 1990 and offers this remembrance.

To be sure, Ned had been at the fresh-air life long before arriving at Dartmouth. "My dad started it," he once told me. "He had me on skis when I was three. I was small and the mountains were very big." At Holderness prep school in New Hampshire, Ned took up cross-country skiing "'cause all the best racers were racing downhill. I had these ratty old skis, and over Christmas I went around and around our garden in the backyard double sessions, morning and evening. The January time-trials remain my proudest moment in skiing. I was coming toward the finish line and the guy in front of me fell and I won. I have never given up since. My whole life since then has been a life of getting tilings done. But just barely getting things done. I barely won that time-trial, barely made the Olympic team, succeeded on Mckinley after falling once. The thing is, though, ever since that afternoon at Holdertiess, I have gotten things done."

He starred at cross-country at Dartmouth. He confirmed in Hanover that, above all else, what he loved was "being out in the air." After college and the Olympics, he had his "brieffling with being a serious person," but business school lasted all of one day. And then it was back into the air. Over the years, among other things he got done, he summited Everest and skied all the way around it, skied the Mountains of the Moon on the border between Uganda am! Zaire, made the first telemark descent of 2 2,834-foot Aconcagua in Argentina, was among the first Americans in a half-cen-McKinley. With three buddies, he rowed a 28-foot aluminum boat across Drake Passage, open water that connects the Atlantic and Pacific, and experienced some of the worst sea-level weather in the world. Seven hundred-twenty miles and 13 hellish days later, Gillette stepped onto the ice of Antarctica and broke into a grin. tury to climb in China when he summited—then skied off—24,757-foot Muztagata. The two adventures he'll be remembered for: With Galen Rowell, he was the first to make a one-day ascent of

He was always doing that: grinning and laughing. Some saw hinl as the clown prince of adventuring since his ideas often bordered on the wacky, bill the fact is: I le was very methodical about what he was doing, because the things he did were so ferociously difficult, He hag Scant margin for error in his life, and he knew it. But he was a happy guy, and so the adventures seemed happy-go-lucky. The word "'boyish" was often used unfairly in reference to Med, as if he were irresponsibly footloose, or at least non-serious. Ned was boyish, certainly, but in the way thata boy is more wide-eyed, excited, and hopeful than a man. Other adventurers are obsessed with bagging peaks, getting notches in the belt, putting things behind them. Ned always seemed focused on what was ahead, what was next. "Life doesn't stop With one Experience." he once said.

Susie knew it. "I'd heard about Ned," she told me when we met in 1989, a few months before she and Ned were wed. "I did have an idea of what I was getting info. I did not know some of it would be quite so extreme." Ned said of his marriage, which was as good, if as strange, as any: "Since Susie is new to this adventuring stuff, she's even more gungho than I am. Hook at it this way: Now I can bring my home life with me."

And so he did. That worried those of us who knew Susie and Ned. Off-limits had no meaning for Ned, nor did "dangerous." His friends never said it aloud, but we half expected to hear bad news one day. Not news like this, of course: being set upon by bandits with shotguns. We expected we might hear bad news from a higher elevation. From way up up in the thinner, finer air. That's where Ned found he had to go, for there he was most alive. He once told me that the highest elevations made him feel as if he were in Heaven.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

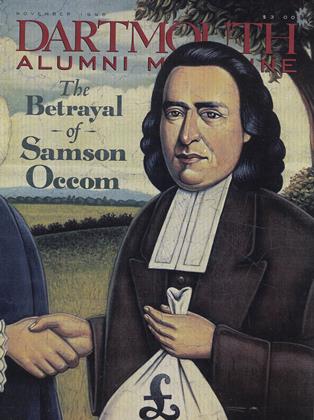

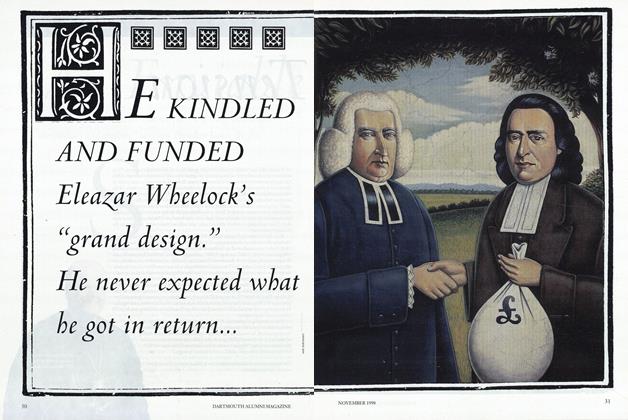

FeatureThe Betrayal Of Samson Occom

November 1998 By Bernd Peyer -

Feature

FeatureThe Mystery of the Tao

November 1998 By Rebecca Bailey -

Feature

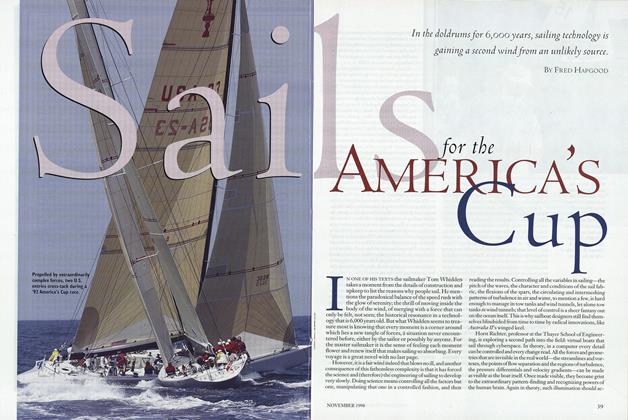

FeatureSails for the America's Cup

November 1998 By Fred Hapgood -

Cover Story

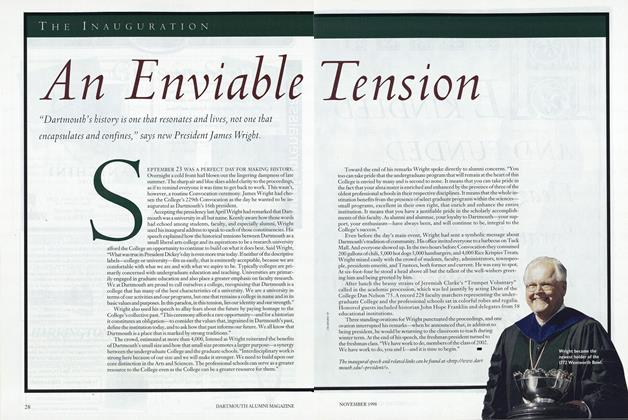

Cover StoryThe Inauguration

November 1998 -

Article

ArticleThe Problem with Romantics

November 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

November 1998 By Jeffrey D. Boylan, R. James "Wazoo" Wasz

Article

-

Article

ArticleThis number of The Magazine

December, 1919 -

Article

ArticleBACK FILES OF ALUMNI MAGAZINE DESIRED

June, 1923 -

Article

ArticleA Chance for Clippers

May 1951 -

Article

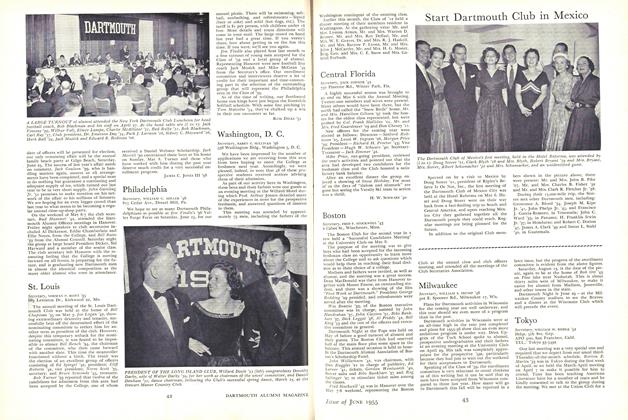

ArticleStart Dartmouth Club in Mexico

June 1955 -

Article

ArticleClub Calendar

MAY • 1988 -

Article

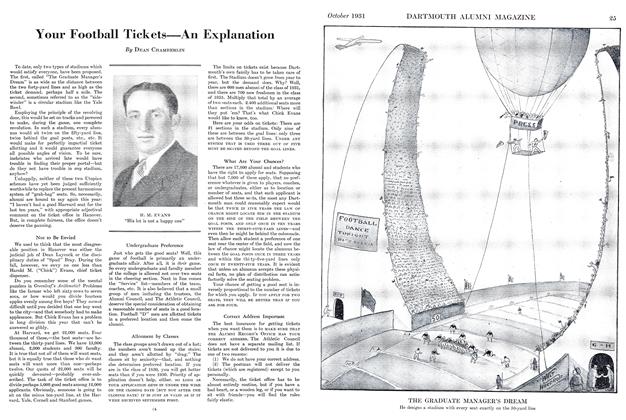

ArticleYour Football Tickets—An Explanation

OCTOBER 1931 By Dean Chamberlin