Relationships may be made in heaven, but it takes down-to-earth realism to keep them from becoming hell.

CAN MEN AND WOMEN be friends? The debate in Psychology 53 played out like a scene from When Harry Met Sally. The female students gushed about their many friendships with men. The men said nothing. The women declared that their opposite-sex friendships were purely platonic, never awkward. The men said nothing. Finally the men, nudged into discussion, admitted they were skeptical, even pessimistic, about the whole idea.

Turning to more dispassionate data, Professor Todd Heatherton read to the class the results of the only scientific study he could find on malefemale friendships. The good news: As long as sex wasn't an issue, the friendships were strong. The bad news: Sex was an issue 93 percent of the time.

Few courses at Dartmouth have more immediacy for students than Heatherton's course on personal relationships. The class is so popular that more than 100 students signed up for 30 openings the first time it was offered; Heatherton let in 70.

Relationships are always vital. But college students are tossed into a maelstrom of friendships and intimacies, fed by hormones and untested freedom. The campus is a laboratory for the theories pondered in Heatherton's class. The course's personal relevance can also be a danger, Heatherton cautions. Everybody has anecdotes about any day's lecture: a stay-at-home father or a troubled sibling, a failed romance or difficult friendship. True, Heatherton drolly company. "Butthe prof makes sure the class sticks to psychology, not Sally Jesse. "I didn't want it to simply be a talk show," he said. "But at the same time, people's beliefs and views and personal experiences should inform the nature of the course." mentions his own young children one day when the classroom discussion turns toward the loss of freedom of new parents: "If you're like my wife and me, who never went out anyway, it's just the same but with

Heatherton starts with sibling relationships "For most people, that's their sole experience with violence," he says—and moves through friendship, dating, marriage, and childrearing. In addition to textbooks and research studies, students read relationship-heavy novels by Somerset Maugham and D. H. Lawrence. A recurring theme is why relationships are so difficult and especially, why so many romantic relationships flop. Adding the break-up of long-term, unmarried couples and the numbers of people who stay in unhappy relationships to the 50 percent divorce rate, Heatherton estimates that close to 70 percent of romantic relationships fail in this country.

Heatherton champions the theory, supported by research, that fingers the decline of civility among married couples as one culprit. As psychologist Rowland Miller wrote in 1997, "Married people are meaner to each other than they are to total strangers." Heatherton reels off the reasons why: the novelty of the relationship fades; spouses learn unflattering things about their mates; they have unrealistic expectations about the relationship. When people hear "for better or for worse" in their marriage vows, he says, "most people assume the 'better' part."

Heatherton argues for the therapeutic value of being nice to those closest to us, citing a selfish reason: feeling good about ourselves. Flirting, for instance, nurtures self-esteem. When people flirt, they try to be witty and charming. They tell stories of their successes. "When I make that good impression on you, I've also made a good impression on myself," Heatherton says. "And I temporarily feel better about myself for having done that."

The same principle applies to long-term relationships, he argues. When we are nice to our spouses, they like us more and treat us better. And that makes us feel better about ourselves. "It is paradoxical that we put our biggest efforts into pleasing other people and we come home and put on our sweatpants and take off our makeup and eat with our fingers—sort of being the 'real me,'" he says. "So many people think that when you finally are with the person of your dreams, you can let down your guard and be the real you. That's probably not good for relationships. It's not only not good for relationships, it's not good for ourselves."

Yet the interplay between self-esteem and other kinds of relationships can be tricky, Heatherton has found. He has been studying the class of 1999 closely to see how they feel about themselves and about their classmates. First students filled out surveys that allowed Heatherton to measure their self-esteem. Then they were asked to list people in their class that they liked. (To keep such potentially explosive data confidential, all student names were coded.) Contrary to conventional wisdom, Heatherton found that students who really like themselves were not necessarily liked by others. "How you feel about yourself is not necessarily a good reflection of how other people feel about you," he said. "It does call into question the assumption that if we give our children high self-esteem, they will be liked."

Throughout the course, Heatherton assigns groups of students to report back to their peers on research topics. One day last spring, the debate was "Children Bring Life Meaning vs. Children Are a Menace to Mental Health." The first group backed up conventional wisdom with research: raising children satisfies the need for social bonding, for instance. And although studies show that the birth of a child disrupts marriages, the students found, many couples reported an increased feeling of partnership. A 1981 survey found that two-thirds of married people reported that parenthood brought them closer to their spouses; just ten percent reported that it drove them apart.

But the anti-children group cited other studies that found that couples without children are happier with their lives than couples with children. Couples with children have two peaks of happiness in their marriage, according to one study: one, before the birth of the first child, and the second, after the last child has left home. And researchers found that after the birth of a child, men began working more, saying it was less stressful than home life. "Making them is fun enough," concedes the male student making the presentation, "but having children is the absolutely worst thing two spouses can do to their marriage."

In child-rearing, as well as marriage, Heatherton preaches anticipation and preparation. "People have these fairy-tale ideas about what relationships will be like," he says. "If people are aware that relationships are difficult because passion tends to fade, that familiarity breeds contempt, and that we start taking our partners for granted—knowledge of these things helps people have realistic expectations."

Flirting nurtures-self-esteem as well as relationships.

KATHLEEN BURGE, a frequent contributor to Syllabus, is getting married in May.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

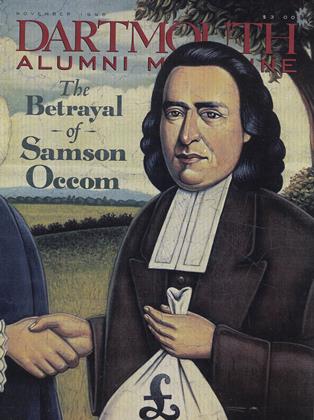

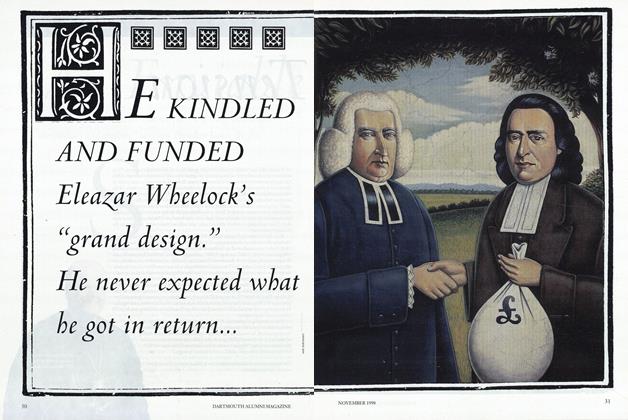

FeatureThe Betrayal Of Samson Occom

November 1998 By Bernd Peyer -

Feature

FeatureThe Mystery of the Tao

November 1998 By Rebecca Bailey -

Feature

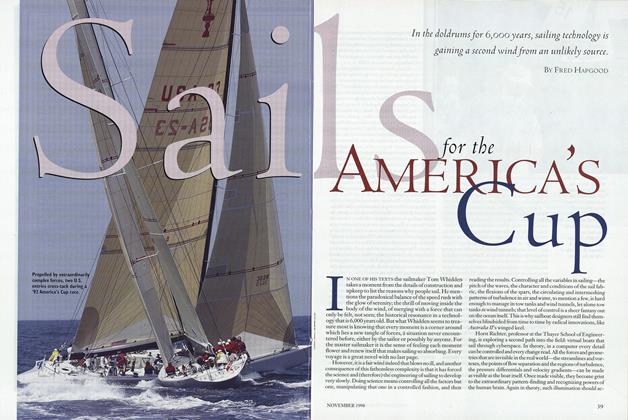

FeatureSails for the America's Cup

November 1998 By Fred Hapgood -

Cover Story

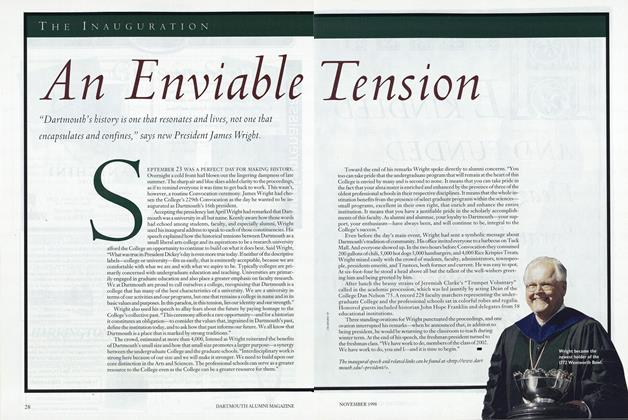

Cover StoryThe Inauguration

November 1998 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

November 1998 By Jeffrey D. Boylan, R. James "Wazoo" Wasz -

Article

ArticleThe Last Adventure

November 1998

Kathleen Burge '89

-

Article

ArticleWhen Bad Things Happen

January 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleOne for the Road

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleWhat Beethoven Heard

NOVEMBER 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleGender and Power in Shakespeare

OCTOBER 1997 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleTales from Uncle Anton

JANUARY 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleMother Russia's Daughters

DECEMBER 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89