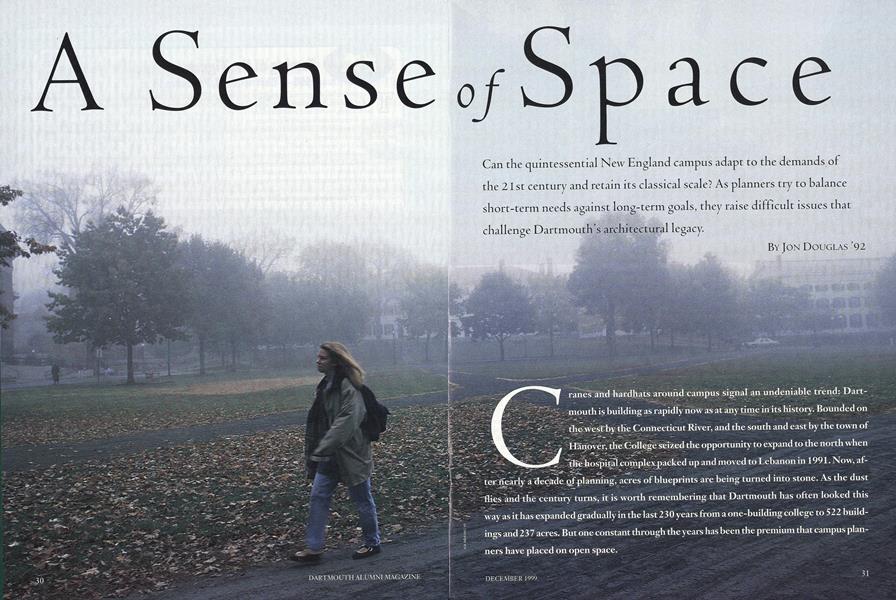

A Sense of Space

Can the quintessential New England campus adapt to the demands of the 21st century and retain its classical scale?

DECEMBER 1999 Jon Douglas ’92Can the quintessential New England campus adapt to the demands of the 21st century and retain its classical scale?

DECEMBER 1999 Jon Douglas ’92Can the quintessential New England campus adapt to the demands,of the 21 st century and retain its classical scale? As planners try to balance short-term needs against long-term goals, they raise difficult issues that challenge Dartmouth's architectural legacy

Cranes and hardhats around campus signal an undeniable trend: Dartmouth is building as rapidly now as at any time in its history. Bounded on the west by the Connecticut River, and the south and east by the town of Hanover, the Gollege seized the opportunity to expand to the north when the hospital complex packed up and moved to Lebanon in 1991. Now, after nearly a decade of planning, acres of blueprints are being turned into stone. As the dustflics and the century turns, it is worth remembering that Dartmouth has often looked thisway as it has expanded gradually in the last 230 years from a one-building college to 522 buildings and 237 acres. But one constant through the years has been the premium that campus planners have placed on open space.

It's not so much that the campus is getting bigger as it is filling out to the size required by a premier undergraduate college with lofty research ambitions. After decades of crowding faculty into small offices and students into small dorm rooms, Dartmouth is using the master plan to help relieve its campuswide space crunch.

With $100 million worth of buildings currently under construction and an additional $100 million worth of new buildings in the planning stage, Dartmouth's campus is on the cusp of a change potentially more defining of the College's sense of place than anything that has happened since President William Jewett Tucker, class of 1861, expanded the academic and physical scope of Dartmouth at the close of the last century. The flurry of construction set in motion by Tucker, lasting from 1893 to 1940 and producing 56 buildings, set in stone a campus ambiance that symbolizes the College for all living alumni. At the dawn of a new century, however, the campus balance is shifting northward to properties formerly occupied by the old hospital.

The man responsible for establishing the blueprints and the framework for the debate is Lo-Yi Chan' 54, a specialist in campus planning (see "The Master Planner," p. 33). Chan's third update of the campus plan was released last spring. If it is faith- fully followed, when the '00s return for their 50th Reunion, they should feel right at home. To appreciate how Chan plans to preserve the character of campus and create opportunities for future architects, one has to realize he didn't start with a clean slate. His job is much more difficult. He has to build on two centuries of good planning. The stakes are high.

CAMPUS PLAN BY FIAT

Dr. Wheelock set the tone for today's Dartmouth when he cleared the forest and built his campus. In reality, however, the seminal date in the history of Dartmouth planning is 1808, when College Trustees voted to prohibit construction on the Green. That action was the single most important precedent for planning the campus today. The Green defines the character of Dartmouth's campus—a fact carefully noted in Chan's plan: "Open space is paramount to the creation of a campus. Buildings gain significance when they are integral with that open space." In other words, Dartmouth Row looks so good because the Green is open and alive with the passing and playing of hundreds of students. Moreover, Chan says, "Dartmouth has one of the finest campuses in the country. What makes it work so well is the College Green."

Once the decision was made to keep the Green green, Dartmouth didn't need campus planners for the next two decades. Classrooms, dorm rooms, the library and chapel were all inside Dartmouth Hall. The expansion of the campus in the 1820s, during which Wentworth and Thornton halls formed Dartmouth Row, was die first time that Dartmouth conceived of buildings in related groups, another precedent the College has maintained to this day.

The next great period of campus growth came during the administration of President Tucker in the 1890s. "Tucker so fundamentally changed Dartmouth, developing the College on a scale that dwarfs everything since," says Timothy Rub, director of tecture. The College commissioned architect Charles Alonzo Rich, class of 1875, to create its first master plan in 1893. Over the next 20 years Rich designed more than a dozen buildings that still survive, including Fayerweather, Richardson, Wheeler and Massachusetts dormitories; College, Robinson, Tuck (later McNutt) and Parkhurst halls; and Webster, Wilder and Alumni Gym. Rich's conception of each building included plenty of open space around its edges and maintained architectural connections between groups of buildings, most of which are in the Georgian style of brick walls and copper roofing. This is the Dartmouth that we know and love today.

Fortunately for the class of 2000, the master planning of the 1920s was successful in envisioning the future needs of the College. While not every proposed structure in the comprehensive 1922 master plan of John Russell Pope was actually built (see "Unbuilt Dartmouth," p.35), two elements define the current campus. Pope designed Tuck Mall, bolstering the precedent for open space, and his placement of Baker Li- brary at the head of the Green declared the library the literal and figurative heart of the College. Pope's contemporary, Jens Frederick Larson, the primary architect of the 19205, transformed paper plans into brick with his designs for Baker, Carpenter, Sanborn and Silsby. Their Neo-Georgian attributes enjoy a collective appeal among alumni.

THE COLLEGE ON THE HILL (AND BEYOND)

As the millennium draws to a close, the number of undergraduates is the same as it was 25 years ago. Why then, one might wonder, does the College need so many new buildings? A number of factors come in to play. "Students coming to campus need more space than they used to," says College President James Wright. And more space translates into larger dorms. Double rooms in Gile average about 240 square feet. Doubles in Andres, one of the College's newest dorms, average 350 square feet. Moreover, although the number of undergraduates on campus isn't increasing (undergraduate enrollment is capped at 4,300), the number of people on campus has, and this growth will continue. The graduate student population has grown from 17 percent of the student population to 25 percent. The number of administrators has been increasing by about 1.5 percent per year, so there are 800 more of them on campus than there were 20 years ago. During the same 20 years, the College increased the size of the faculty by 25 percent, added 14 new academic departments. In short, the College needs spaces for all these people.

Besides needing new buildings to house new subjects and faculty, new facilities are needed to support what is already here.

New buildings aren't ends in themselves, says President Wright, but they are necessary to maintain the quality of teaching and research, particularly in the sciences. Old multipurpose buildings such as venerable Dartmouth Hall are no longer adequate for specialized learning. In this arena of classroom space, the College has lost ground. From 1965 to 1989 only $13 million was spent on academic facilities, compared to $21 millions for athletics and $24 million for dorms and dining facilities. As a result, there are actually fewer classrooms today than when Wright began teaching at the College in 1970 because, as the size of the faculty expanded, smaller classrooms were converted into offices.

Faced with limited acreage and an insatiable appetite for floor space, the College's edifice complex appears to leave Chan with only two options: either increase the density of College buildings or spread out beyond current boundaries. The first option might make Dartmouth more like M.I.T., an urban university where every building is physically connected. And the latter option might echo Middlebury, where the campus is so spread out that students ride to class. Or Duke, whose west and east campuses are separated by more than a mile; shuttle buses run back and forth all day. To date, Dartmouth has gone right down the middle: Additions to overcrowded buildings, such as the Science Center adjacent to Wilder Hall, nibble away at the open space, while growth north of Baker means fewer parking spaces on campus and almost certainly a shuttle to move employees out to satellite parking lots.

The current construction boom is evidence of how the Dartmouth master plan is already taking shape. One of the plan's primary recommendations is the creation of new academic facilities north of Baker. The just-opened Moore Hall for psychology is just the first in a series of large new complexes that will include the soon-to-be-constructed Kemeny Hall for mathematics, an as-yet-unnamed biology building and the state-of-the-art Berry Library.

While the design of the Berry Library probably raised the most architectural hackles in Hanover since the Hopkins Center was built, there is more to the debate than the critics' claim that the library's length and columns evoke a New England mill. The design of an individual building is only part of the equation. Chan's job as a planner is to balance the known programmatic needs of the College with architectural principles that will last for generations. When considering the relationship of buildings to each other, as well as their scale and materials, Chan's primary goal is to preserve connections between the old and new Dartmouth. "There's a real danger that we'll create a north campus separate from the main campus," says Chan. His vision for the northern end of campus is potentially as important to the future College as the Trustees's 1808 vote prohibiting construction on the Green.

Chan's plan calls for the series of new open spaces north of Berry Library, an idea first proposed by planner Denise Scott Brown in 1988. This series of classroom or residential buildings will provide a walkway parallel to Main and College streets. Whether students and alumni embrace Chan's new "Berry Row" is predicated upon what future needs the College identifies and how architects shape new buildings around those needs. Chan says that even if later planners carry out his wishes for Berry Row, it won't happen immediately. The College's plan is to complete Berry and the adjoining academic wing, Carson Hall, and then sit back for a decade or so to see how the community adapts to the open space. As the series will likely be constructed one building at a time, we won't understand how well those buildings succeed in defining Berry Row until the entire grouping is completed a couple of decades from now. In the meantime, we have to accept that the main entrance to Moore Hall isn't facing a street. The main entrance faces the as-yet-unbuilt Berry Row.

However, where Chan sees an opportunity, the Hood's Rub raises a concern about using Berry Library as the focal point of the north campus. Berry's design, like Moore's, depends on a vision of north campus that may never be fulfilled. Then what happens? Indeed, some on campus have already seen the future and feel it doesn't reflect the vision of Chan's campus plan. Art history professor Joy Kenseth, who spearheaded opposition to the Berry project two years ago, still finds the exterior design and positioning troubling. "What I found problematic was the mass of the building and the way it was crowded next to surrounding buildings, which is quite unlike what happens to most buildings on the central campus," she told The Dartmouth.

Rub says there is always room for rich and sophisticated debate about the merits of a particular building. "Even if you hire the best architects, you won't get successful buildings 100 percent of the time," he notes. "Architecture is fundamentally the expression of an artist." Which brings up another point about campus plans. Campus plans are not unlike constitutions: Once adopted, well-credentialed experts will endlessly debate the implementation. Hence a hallmark of good planning is the ability to balance current needs against anticipations of the future. The ink was barely dry on Chan's latest plan when the Trustees announced their social and residential life initiative. While the initiative details will be ironed out over the next year, it is a solid bet that more dorms, dining halls, social spaces and perhaps even a student center might be part of the campus mix in the near future. (See "The Shape of Things to Come?" p.17.)

DENSITY VS. SPRAWL

One way to solve the College's space problem might be to increase the density of buildings on campus. And that might not be a bad idea. The Hood Museum, which now connects the Hopkins Center and Wilson Hall, is an example of a successful trade-off of green space for density. "The center of campus is actually less dense than it has been in the past," argues Scott Meacham '95, who has a master's degree in historic preservation and maintains a comprehensive web site about Dartmouth architecture (www.meachams.com/scott/darch). "Putting another building in front of Sanborn could make the Green even stronger as an open space."

That isn't likely to happen anytime soon. While President Wright is committed to keeping Dartmouth a walking campus for students and faculty, Chan's plan includes the off-campus relocation of employees deemed non-essential to the College's academic mission. On the surface Dartmouth looks the same, but a careful reading of the phone book reveals that alumni records are no longer maintained in Blunt Alumni Center, but in a bank building on lower Main Street. Other administrative departments are slated to move to a new parking/office complex under construction across the road from the Hop. Others may move to a suburban-style office park along Route 10 in Lebanon.

Even moving people off-campus doesn't provide enough space however. Open space within an easy walk to the Green is finite, and if the trend toward off-campus expansion continues, it may fundamentally alter how future generations perceive Dartmouth. For some students Dartmouth is no longer a walking campus. The College's organic farm is 3.5 miles from campus and the pottery studio is in Norwich. A rugby clubhouse will occupy land on Hanover's Reservoir Road, across from the far end of the golf course. "At the end of the next century, Dartmouth may no longer be a walking campus," says Wright. Athletic Director Dick Jaeger '59 agrees, but says it is important for Dartmouth to build its facilities as close to campus as possible, rather than in an outlying area, as at Columbia, where the football team has to travel several miles to play in Morningside Heights. "There could be a time in the future when we bus our athletes to a complex far away," says Jaeger, "but we don't want to have to do this."

For many alumni, the best master plan is one in which nothing ever changes. Sentiments aside, the College's master plan must be flexible enough to adapt to unforeseen changes in Dartmouth's environment. "Master plans can't be blueprints of the future that fix where you're going," says Wright. "They evolve."

The fundamental tension of master planning then, is to balance the architectural tastes of the present—for both individual buildings and the connections between them with what the campus will need a hundred years from now. The master planner's job, in essence, is to hold Dartmouth in trust for the future. And for visitors to consider Dartmouth a beautiful campus in a hundred years, one that is neither too dense nor too sprawling, the architects of the next century will need to understand the wisdom of Chan's plan. Only the youngest readers, however, will live long enough to see whether tomorrow's College will embrace Lo-Yi Chan's vision.

The Hood Museum, nestled in a courtyard between the Hopkins Center and Wilson Hall, is widely regarded as the most successful architectural project of recent years, though it ignores Dartmouth's general philosophy of preserving open space between existing structures and mimics M.I.T.'s model of interconnected buildings.

Chan suggests that the Hopkins Center represents the best of Modernism. Given enough time, the building could evolve into a signature for the College.

A less successful modernist project than the Hopkins Center is the Choate dormitories. There's a reason students refer to the "habitrails" that connect individual pods: Modern buildings rarely attempted to connect to the rest of campus.

Although Dartmouth Hall is obsolete as a classroom space, the view toward Dartmouth Row will remain unchanged. The campus plan calls for Dartmouth to preserve its traditional historic structures.

Three decades after it was built, Butterfield Museum was razed to make room for Baker Library proving that even the best plans can't anticipate every new trend. Butterfield was doomed because texts superseded objects as items worthy of study. When the geologic and natural history treasures became less important than the library collection, the museum had to go.

The Master Planner Although everyone has an opinion about Dartmouth's architecture, few alumni actually get to leave their mark on campus. Lo-Yi Chan '54 is a rare exception. As both the designer of the Rockefeller Center and the author of three editions of Dartmouth's long-range architectural plan over the last dozen years, Chan has left his permanent handprint in the developing campus sidewalk. Take a stroll down East Wheelock Street and think about this piece of Chan's legacy: one proposal for the design of the Berry Sports Center had it positioned in an L- shape with Alumni Gym; the rear of the building faced Park Street and the town of Hanover. At Chan's insistence, Berry was rotated 90 degrees clocke, thus avoiding a symbolic snub of the town. (The quarter-turn was much more easily accomplished before construction began, or it might have been necessary to add King Kong to the College payroll.) While Chan has only been employed by Dartmouth since the early eighties, he has been connected to Hanover since he moved there in 1942, when his father, Wing-tsit Chan '80H, became Dartmouth's first professor of Asian studies and the head of the only Asian family in town. As a high-school junior, the younger Chan's independent project was to design an addition to Hanover High School; he has kept an eye on local architecture ever since. After graduating from Dartmouth, Chan rose to prominence as an architect with a master's from Harvard, an apprenticeship with I.M. Pei and a professional practice in New York specializing in socially based projects. He retired from Prentice and Chan in 1994, the year the firm won the Medal of Honor from the American Institute of Architects. Chan has since continued full-time his second career as a campus planner, contributing to master plans at Colgate University, Philips Academy and the Lawrenceville School. For nearly two decades and under four presidents, this master planner has been planting architectural seeds at Dartmouth that have finally begun to bear fruit. What does Chan consider his legacy at the College? "One, that the idea of historic preservation has become institutionalized into policy, he says. "And two, the expansion of the campus to the north. That's about preserving the character of the existing campus, and creating a new Dartmouth that ties together with the old." Jon Douglas '92

Unbuilt Dartmouth One of the most fascinating aspects of master planning is imagining the buildings that never were built. Dartmouth might look very different today if these projects had ever broken ground: • Architects Venturi Scott Brown once proposed creating the north campus around a duck pond. The idea wasn't seriously considered by the College. • A fifth building on Dartmouth Row was planned for the site of the current Rollins Chapel in 1838 as a symmetrical counterpart to Reed. The idea was dropped in the 1840s due to lack of enrollment. • Alumni Memorial Hall was proposed for the site of Webster Hall in 1895 as a secular counterpart to the College church, which then stood in front of the current Sanborn House. • A chemistry building was to be built in the 1890s on the site of the current New Hampshire Hall. • Building a Gothic chapel on the hill in College Park was a favorite idea of President Ernest Martin Hopkins 01. • Dartmouth House, a massive student union proposed in the late 1920s on the site of the current Hop and Hanover Inn, contained a 3,100-seat auditorium, a freshmah commons, a cafeteria and grill, nine private dining rooms, living quarters for bachelors and four bowling alleys. Seventy years later, Dartmouth has still not fulfilled the need for bowling alleys in Hanover. • A classical Greek amphitheater was proposed (twice) in the 1920s first for the end of Tuck Mall and later for the Bema.

The Big Digs There are hardhats all over campus. But four projects stand out because of their size (and the fact that there usually is a giant crane marking the site.) Berry Library Location: Behind Baker Library Size & Cost: 153,000 sq. ft.; $54 million Architect: Robert Venturi Groundbreaking: May 1998 Completion: Summer 2000 Science Center Location: Adjacent to Wilder Hall Size & Cost: 22,000 sq. ft.; $22 million Architect: Centerbrook Groundbreaking: July 1998 Completion: December 1999 Moore Psychology Building Location: Maynard Street Size: 100,000 sq. ft.; $30 million Architect: Robert A.M. Stern Groundbreaking: September 1996 Completion: September 1999 Whittemore Hall Location: Tuck School Size: 50,000 sq. ft.; $13-15 million Architect: Goody, Clancy & Associates Groundbreaking: May 1999 Completion: December 2000

JON DOUGLAS '92 is a freelance writer living in Boston,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

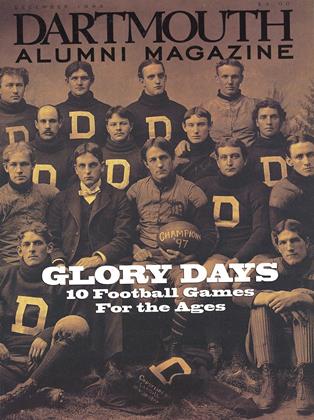

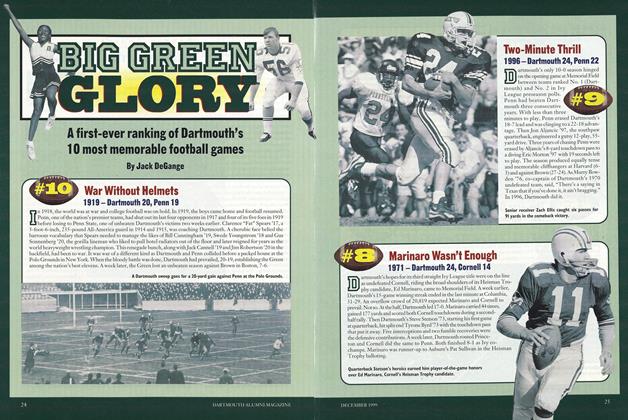

Cover StoryBig Green Glory

December 1999 By Jack DeGange -

Feature

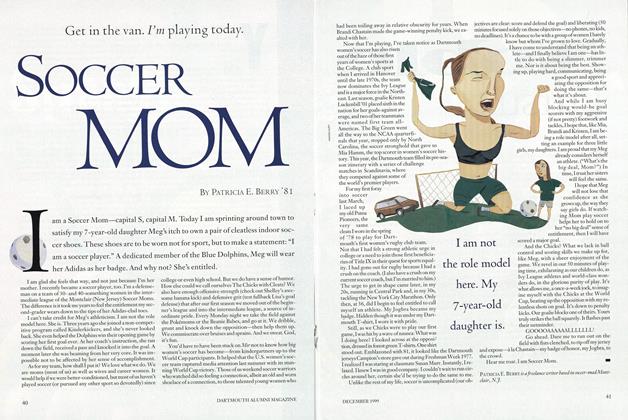

FeatureSoccer Mom

December 1999 By Patricia E. Berry ’81 -

Feature

FeatureStrange Science

December 1999 By Shirley Lin ’02 -

Feature

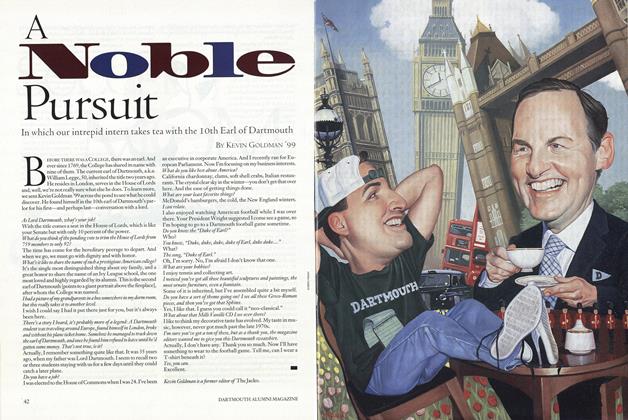

FeatureA Noble Pursuit

December 1999 By Kevin Goldman ’99 -

Article

ArticleMother Russia's Daughters

December 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleVaried Experiences, Common \alues

December 1999 By President James Wright

Features

-

Feature

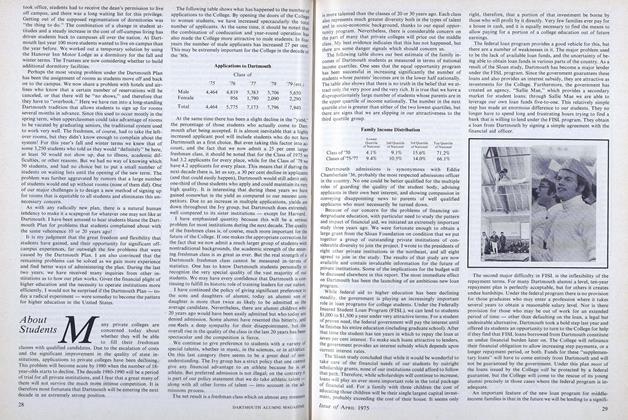

FeatureAbout Students

April 1975 -

Feature

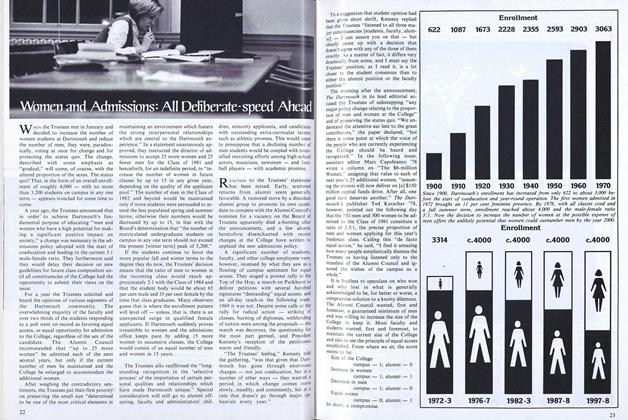

FeatureWomen and Admissions: All Deliberate-speed Ahead

March 1977 -

Feature

FeatureNext Month: A (Not Altogether) New Look

June • 1988 -

Feature

FeaturePsychology at Dartmouth

February 1958 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Feature

FeatureChange and Challenge

JULY 1965 By HAROLD KING DAVISON '15 -

Feature

FeatureBuilding for Today—and 1969

February 1951 By PROF. JOHN P. AMSDEN '20