Revolution and war, not bourgeois feminism, made women the keepers of culture.

Four centuries before The Rules, Russian women had The Domostroi. Instead of

instructing women how to snare men—arranged marriages took care of that—these rules covered the sequel: managing a household. Penned by an unknown author, they left little of a woman's life to her own imagination. The ideal

woman, they instructed, was never idle. She never kept secrets from her husband, and she consulted him about everything. She could prepare many nice mutton dishes. And she never gossiped. These carefully scripted roles for women and men—who were instructed to beat their errant wives—laid out domestic life from the metaphysical to the mundane.

Now, 400 years later, TheDomostroi is back. In the 1990s it was reprinted several times in Russianand once in English. If The Domostroi's attention to managing servants and overseeing handicrafts is outdated, not so its demand that women manage the household and live as exemplars of modesty, sweetness and submission.

In their course, "Women in Russia," Russian professor John Kopper and government professor Juliet Johnson chart these cycles in the treatment of Russian women. Both professors found themselves intrigued by this topic during their many trips to Russia. Kopper's closest friends there are a husband-and-wife team of sociologists. For 20 years the wife has tried to persuade Kopper that Russia is a matriarchy, since women have nearly absolute power in some spheres, such as the home. (Kopper has yet to be convinced.) Johnson, a political scientist who studies how the Russian financial system has evolved since 1988, was fascinated by the predominance of women bankers in Communist Russia.

But the status of women in Russia, if intriguing, has often been bleak. From the days of Ivan the Terrible and The Domostroi to the present day, Russian women have never had as much freedom as their Western peers. Nevertheless, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 produced some articulate feminists who had great hopes that the emancipation movement would advance women's rights. The writer Alexandra Kollontai, the most powerful woman of the revolutionary era, argued that since Marxism was a liberation movement, and since women were clearly oppressed, it was time to liberate them. "But there were many women in the revolutionary movement who said that even that was anti- Bolshevik, that you had to concentrate only on class," Johnson says. "And since women didn't constitute a separate economic class, it was bourgeois feminism to pay attention to issues that could be defined specifically as women's issues."

Although womens' rights made little progress, the horrors of the Soviet period produced a new role for women: keepers of the culture. The Soviet regime and World War II killed as many as 50 million Russians in 30 years, mosdy men. Anna Akhmatova, a poet whose husband was executed by the Bolsheviks and whose son was imprisoned, not only survived but used her poetry to chronicle the history of that period of darkness. "Since Russians perceive women as more ethical than men, it would be the logical place to lodge the values of the culture," Kopper says. "Men are perceived as untamed. Continuing the culture does demand complete subservience of the self, almost erasure of the self for a larger cause."

While the fall of Communism a decade ago improved the lives of Russians, it didn't bring great advances in the role of women. Russia's shaky new capitalism and high un- employment are the forces that helped revive The Domostroi. As the Russian economy has shrunk, it has been mostly women who have lost their jobs. "There always was this ambivalence about what women should be doing," says Kopper. "Should they be staying at home or should they be working? So now to reinforce the stay-at-home mom is obviously in the interests of the state. Get them out of the work force to help solve the unemployment problem."

Especially hard hit, observed Johnson during her recent trips to Russia, were women bankers. During the Soviet era, when production, not money, brought power, most bankers (and doctors) were women. "Banking was just an accounting job more or less because money wasn't an important thing," Johnson says. "As soon as it became profitable to be a banker, men no longer wanted women involved. So you'll see advertisements for commercial banks looking for young men, 25 or so, specifically excluding women as a regular occurrence, even though women are the only ones with any banking experience."

Abused women also find little justice in modern-day Russia. The Human Rights Watch recently found that they get scant help from the legal system. Restraining orders do not exist. Police say they cannot find a safe home for an abused wife or force her husband to leave their home. "There's a very strong notion of unbounded, undisciplined, immoral male energy in Russian culture," Kopper says. "Women in general are expected to channel that energy into nonviolent forms." In one acclaimed case, a woman who was being followed by a man confronted him. Confiding that she felt afraid alone on the streets, she asked her stalker to escort her home. Although the man turned out to be a rapist, he didn't touch her. The woman was praised for siphoning his energy away from violence.

A few years ago women seemed to be winning more power in the government. In 1993, in the first elections of the new Duma, a group called Women in Russia won a surprising number of votes. The group's organizers made it known they weren't feminists and didn't plan to challenge women's traditional roles in society. They campaigned on health care and social issues. "It was clear people were voting for them because it was a group that would represent women,"Johnson says. "This was a need that wasn't being met." But in the 1995 elections, the group fared poorly. That year, Johnson says, there was a proliferation of political parties. And opponents, including a major Russian newspaper, called Women in Russia ineffective, saying the party hadn't met its legislative goals.

The most visible women's group today was formed by mothers of soldiers who fought or died in the war with Afghanistan. The peacenik group has lobbied for benefits for the soldiers and has expanded its efforts to seek army reform.

A perennial debate about Russia is whether the country is more European or Asian. Kopper has always come down on the side of Europe. But the treatment of women—more Asian, he surmises- clouds his opinion. For Johnson, though, teaching the class has confirmed her view: One of the mysteries of Russia, a country that spans two continents, is that it embodies the transition between the East and the West.

Under the Tsars, Russian women had littlestatus. Even today they don't have thesame freedoms as their Western peers.

KATHLEEN BURGE lives in Norwich, Vt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

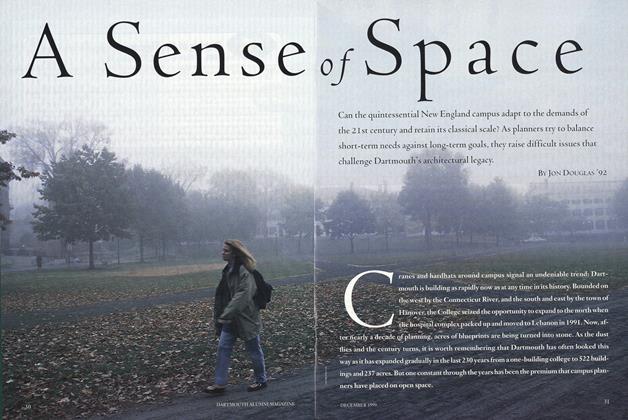

FeatureA Sense of Space

December 1999 By Jon Douglas ’92 -

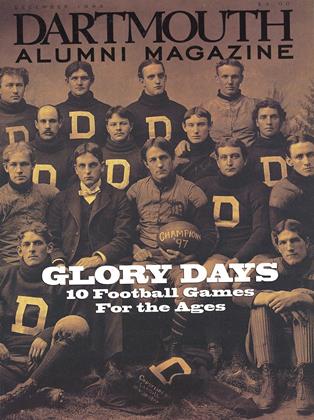

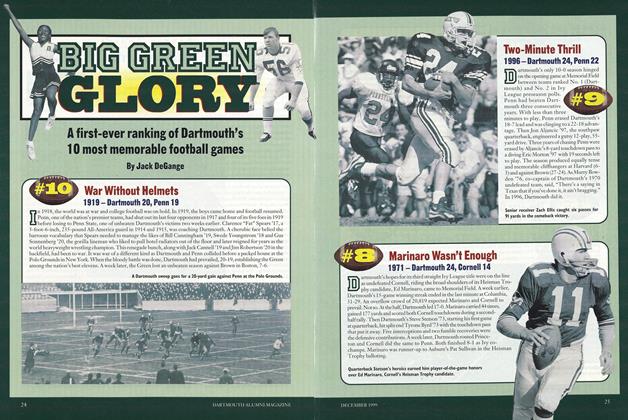

Cover Story

Cover StoryBig Green Glory

December 1999 By Jack DeGange -

Feature

FeatureSoccer Mom

December 1999 By Patricia E. Berry ’81 -

Feature

FeatureStrange Science

December 1999 By Shirley Lin ’02 -

Feature

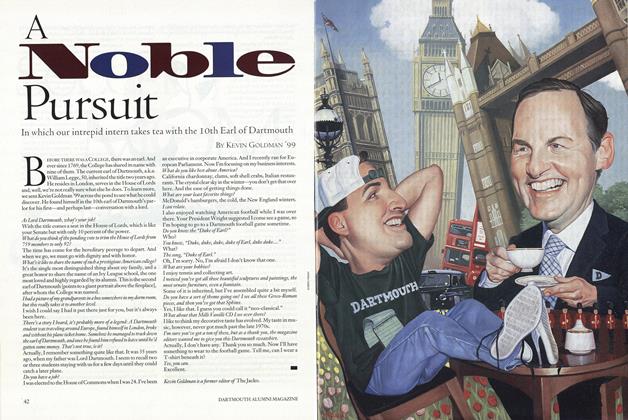

FeatureA Noble Pursuit

December 1999 By Kevin Goldman ’99 -

Article

ArticleVaried Experiences, Common \alues

December 1999 By President James Wright

Kathleen Burge '89

-

Article

ArticleGender and Power in Shakespeare

OCTOBER 1997 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleGender and Power in Shakespeare

OCTOBER 1997 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleMedieval Road Trips

JANUARY 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleNovels that Came in from the Cold

APRIL 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleThe Problem with Romantics

NOVEMBER 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleTales from Uncle Anton

JANUARY 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89

Article

-

Article

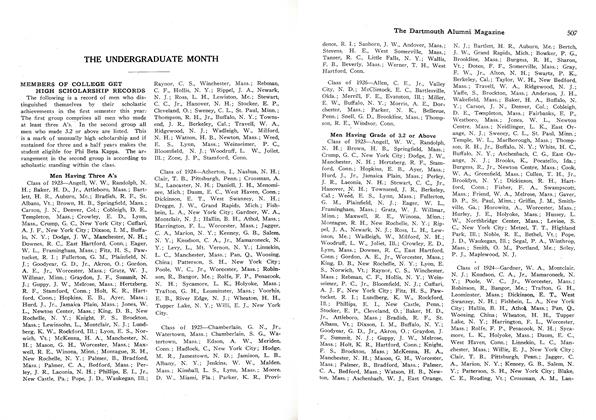

ArticleMEMBERS OF COLLEGE GET HIGH SCHOLARSHIP RECORDS

April, 1923 -

Article

ArticleREV. JOHN W. HAYLEY, SECOND OLDEST GRADUATE DIES

DECEMBER 1927 -

Article

ArticleRAVINE CAMP GONE NOVICE

November 1934 -

Article

ArticleMarine Major

January 1943 -

Article

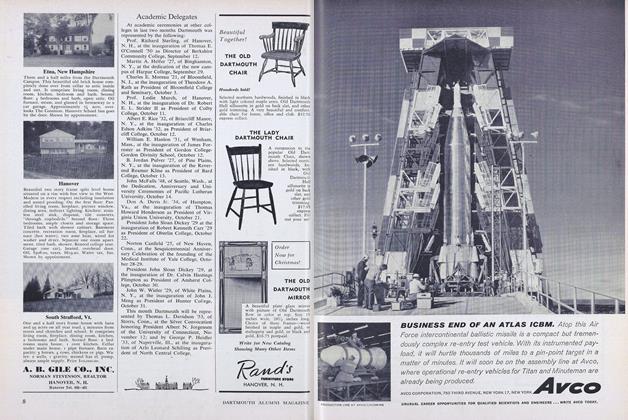

ArticleAcademic Delegates

November 1960 -

Article

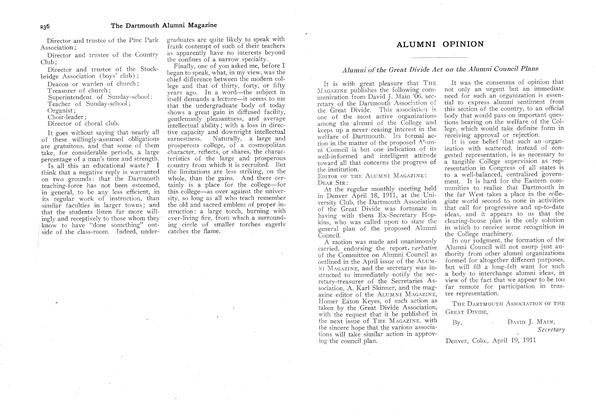

ArticleALUMNI OPINION

May, 1911 By DAVID J. MAIN