Is doing the tried and true worth it? In a letter to a you ng woman deciding how to spend the rest ol her life, the author offers some hard-earned advice.

HEY KIDDO,

During my freshman year at Dartmouth, I used to go around announcing that I was going to be a lawyer, mostly because I thought I was expected, at the highly advanced age of 18, to know what I was going to do for the rest of my life.

Professor Dick Scaldini, who taught me French II and Renaissance literature, once asked me why I decided on law. Nobody had ever asked me "why" before, probably because in 1975 every big-mouthed, smartalecky chick was told that the law would be the right place to spend adult life. I said law would be okay because I could pretty much imagine what my life would be like. Scaldini then quoted me a line he adapted from author Gertrude Stein. He said, "If you can do it, then why do it?" The proverbial light bulb went on above my head. I abandoned the idea of law school and began to think of doing what I never thought I could: becoming a professor.

So after graduation, I headed to Cambridge University. And while there I discovered the riotous possibilities inherent in risk. During my summers in England, I earned money doing odd research jobs for the BBC. At a party (I always went to parties in those days because it meant free food) a producer I'd only just met asked me to appear on a TV show that was a sort of grownup version of College Bowl. It was called (I'm not kidding) Mastermind. You—the contestant sat under a spotlight on a stage and an announcer fired questions at you concerning both a special subject and what was vaguely titled "general knowledge." You had to answer as many questions as you could within three minutes. If you didn't know the answer, you had to say "pass" because you risked losing points with an incorrect response sort of like a particularly demonic and public SAT. This producer explained that the show had been syndicated in seven or eight countries but had never made it to the States. Would I consider, he asked, acting as the official American contestant? I had never seen the program, but my British boyfriend of the moment had, and he whispered that I shouldn't even consider such a thing. He said, and I quote: "You'll look silly." That, of course, made my decision for me. I agreed to be part of the show.

Then I actually watched the terrible, maniacal, sadistic ritual and was unnerved. I chose the life and works of the playwright Tennessee Williams as my special subject. After taking Professor Don Pease's American drama class back in Hanover, I felt equipped to deal with anything a Brit could invent about ol' Blanche, Stanley or The Gentleman Caller. I crammed, memorized and sweated through even the most obscure plays and short stories. On the day of the taping, I had a remarkably bad cold, runny nose and red eyes. I was fuzzy on cough syrup and mad at my boyfriend, who refused to accompany me.

Shockingly, I did all right on the Williams material, but when it came to general knowledge I knew almost none of the questions they asked, many of which had to do with America. Turns out lam vastly, wildly ignorant, despite my fancy education. I could not name all the states along the Mason-Dixon Line. I did not know the highest point in Utah; I didn't know Utah had a high point. I did not know the estimated population of Atlanta. The poor audience members—500 strong were holding their breath in appalled silence as I kept saying "pass" over and over again. In the back of my mind, I was taunting myself in my boyfriend's voice, "See? What do you know? Where's your knowledge now?" I was miserable. Finally, the announcer, no doubt out of sheer pity, asked me one glorious question: "What kind of animal is a guppy?" and I screamed out, "It's a fish!"

There was applause like you never heard. You'd think I just scored a touch down, hit the high note and discovered gold all at once. Clearly the members of the audience were relieved that I finally got one right. They whistled, they stamped their feet, they forgave me my ignorance. I suddenly didn't look silly to them. And at that moment I discovered that anything worth doing was worth doing, period—worth doing well if you could, or doing horribly if you couldn't do better, or anyway, as long as something Gets Done.

So here's my hard-won, long-term, from-the-heart advice: Embrace a sense of possibility even if you're uncertain of the outcome. Face your fears, stare them down, laugh at them. Head out for the territories of your imagination and don't look back.

Take a chance.

With love, Gina

Embrace a sense of possibility even if you're uncertain of the outcome.

REGINA BARRECA, an English professor at theUniversity of Connecticut, Storrs, is a contributingeditor to this magazine. Her most recent book, Too Much of a Good Thing Is Wonderful (.Bibliopola Press), -waspublished in April.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

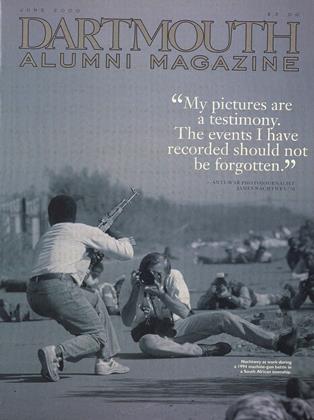

Cover Story

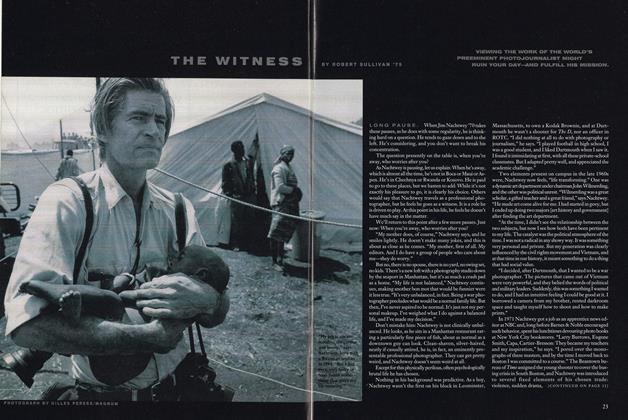

Cover StoryThe Witness

June 2000 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

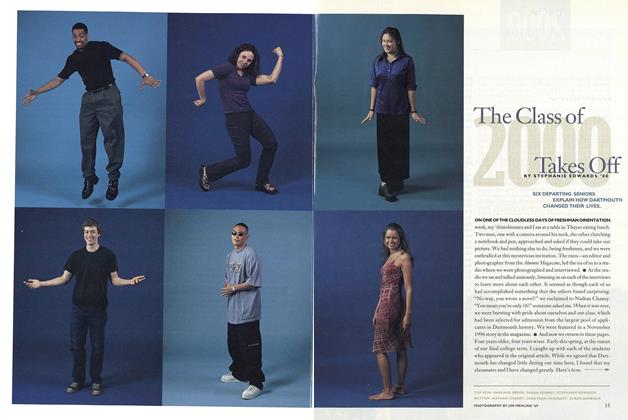

FeatureThe Class of 2000 Takes Off

June 2000 By STEPHANIE EDWARDS ’00 -

Feature

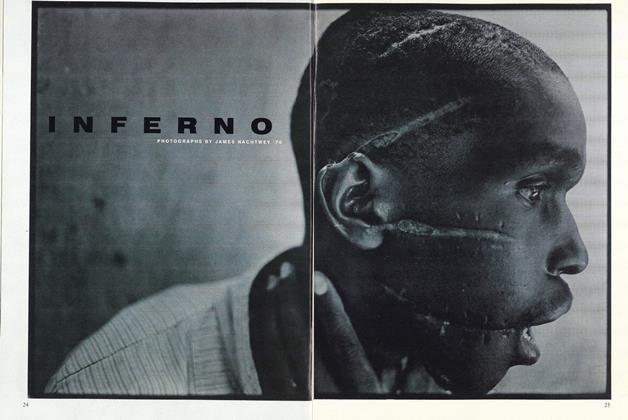

FeatureInferno

June 2000 -

Article

ArticleMinding the Public's Business

June 2000 By President James Wright -

Class Notes

Class Notes1972

June 2000 By Bill Price -

On the Hill

On the HillCampus News and Notes

June 2000 By Jen Whitcomb '00