College presidents are participating more than ever in matters of national importance—despite what you may read.

In recent years college and university presidents have been criticized for our timidity and failure to speak out on public issues. One recent columnist even claimed that we are "weak-kneed and pussy footing." He argued that we should play a much more prominent role in the public discourse than we currently do. My predecessor James Freedman, spoke to this with insight and eloquence. I have some thoughts of my own to add to the discussion.

Critics observe that we have lost the giants who once marked our ranks and walked our campuses. They look back to a time when people such as Nicholas Murray Butler of Columbia University, RobertM. Hutchins of the University of Chicago or James B. Conant of Harvard spoke out on important matters of public life.

In Dartmouth's own history, President William Jewett Tucker, class of 1861, early in the 20th century charged citizens of New Hampshire to follow the moral imperative of reform. Ernest Martin Hopkins, class of 1901, served as assistant secretary of war in 1918, later worked with Franklin Roosevelt, and made public statements on a number of issues, including freedom of speech. Similarly, President John Sloan Dickey'29 publicly addressed the importance of internationalism and civil rights.

The historian in me winces a bit at the criticism of timidity on the part of current presidents. It is an exaggerated if not nostalgic claim to say that there was once a golden age of public discourse wherein university presidents played a dominant role. For every Butler in the 1920s or Dickey in the 1950s, hundreds of their colleagues were absorbed fully in the business of their institutions. Indeed for most of the last century, the popular view of the academic world has been one of an ivory tower divorced from the real business of American life.

The suggestion of present day disengagement is equally exaggerated. Far from being unaware or disinterested in the issues of our time, college presidents today deal with a range of issues that are central to our society. Contemporary presidents are engaged in the full-time business of their institutions: recruiting and retaining faculty, attracting the strongest students, meeting with alumni/ae, dealing with boards, legislatures and government officers, and traveling extensively to raise money in short, trying to manage complex institutions that require a consensus-building style. These are assignments that demand more time and energy today than when our predecessors sat at our desks.

But this explanation is not adequate for two reasons: it accepts the premise that we are less active in public debate, and it excuses this by suggesting that we may not be timid but we are very busy dealing with our local political constituencies, trying to stand for something without offending anyone! If being busy or feeling conflicting political pressure—circumstances that describe many citizens in many walks of life—is sufficient reason for not speaking out on public issues, then our public discourse may well be in peril.

Presidents should not be defensive, nor should the public be pessimistic. We in the academy have accomplished much by doing our own business well. Since World War II this country has seen a remarkable expansion and democratization of American higher education and a tremendous expansion of knowledge. In 1900 only 4 percent of Americans attended college. By 1940 the figure had climbed to 15 percent, and today it has reached 45 percent. American universities are important models, magnets even, for the rest of the world. This accomplishment is an important contribution to the republic and to the public's business.

But this is not the whole story. College presidents have not simply focused on the growth of the ivory tower. In this country, we are now participating in some basic constitutional, political, cultural and intellectual debates that relate to the very nature of American higher education, and, more to the point, to the quality and nature of American life. Dartmouth—her students, faculty, alumni and administration, as well as her president—vigorously takes part in these debates.

These debates have to do with how we constitute membership in our communities, including the importance of diversity and affirmative action. They have to do with the way a society sets priorities and allocates its resources. They have to do with gender relations and the quite remarkable revolution in which we are privileged to participate. They have to do with the abuse of alcohol and drugs in a culture that values individual freedom and choice. They have to do with the cost and accessibility of higher education. They have to do with the importance of basic research. They have to do with the skills, knowledge, understandings and values that our students will need for the new century we have begun. They have to do with health-care delivery and the importance of academic medical centers.They have to do with relating to a world whose activities are increasingly defined by global rather than national constructs. They have to do with the impact of technology on the way we organize ourselves and relate to each other. They have to do with the wave of new ethical issues we confront as our capacity grows to develop and manipulate life's building blocks.

These are not simply campus debates no one recently has suggested that these things are "only academic" in the dismissive way that concept was used in the past. In fact, each of these issues, in different formulations, found expression in the sometimes vigorous debates that marked the presidential primary in New Hampshire. That is why I am not so troubled about our academic life or our public life—and the increasing overlap between them. And that is why I am not so nostalgic for the days of Nicholas Murray Butler or James B. Conant. This is the best time I could imagine to be in my position. Higher education has never been more relevant to American society.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

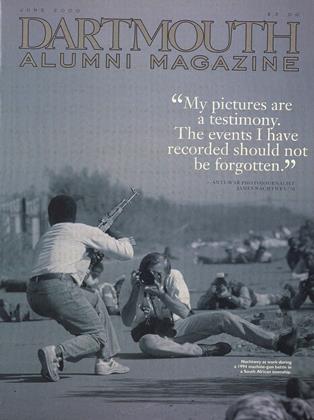

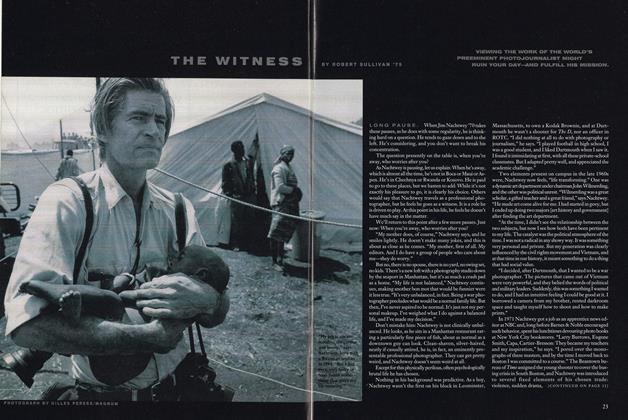

Cover StoryThe Witness

June 2000 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

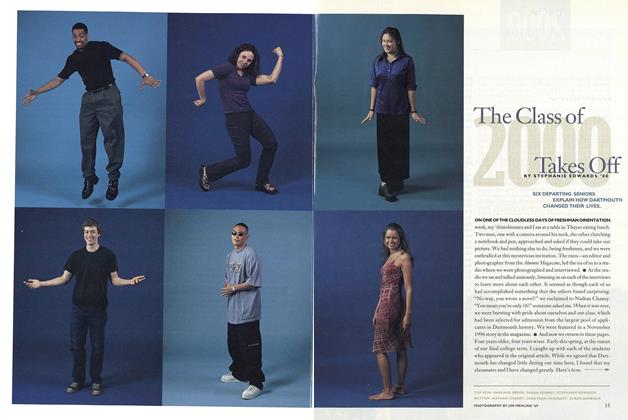

FeatureThe Class of 2000 Takes Off

June 2000 By STEPHANIE EDWARDS ’00 -

Feature

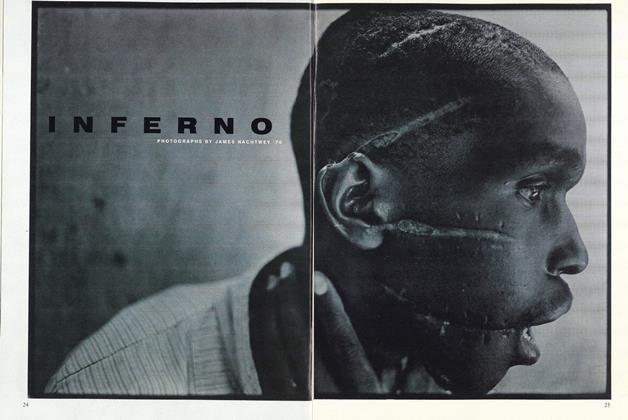

FeatureInferno

June 2000 -

First Person

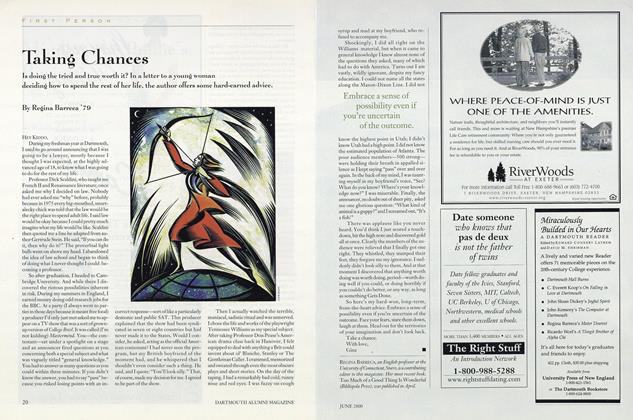

First PersonTaking Chances

June 2000 By Retina Barreca ’79 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1972

June 2000 By Bill Price -

On the Hill

On the HillCampus News and Notes

June 2000 By Jen Whitcomb '00

President James Wright

-

Article

ArticleWhere Do We Go From Here?

JANUARY 2000 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleThe Global College

Jan/Feb 2001 By President James Wright -

The President

The PresidentA Tragic Loss

Mar/Apr 2001 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleExpanding Dartmouth

May/June 2001 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleShock Waves

Jan/Feb 2002 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleA Tighter Belt

Nov/Dec 2002 By President James Wright