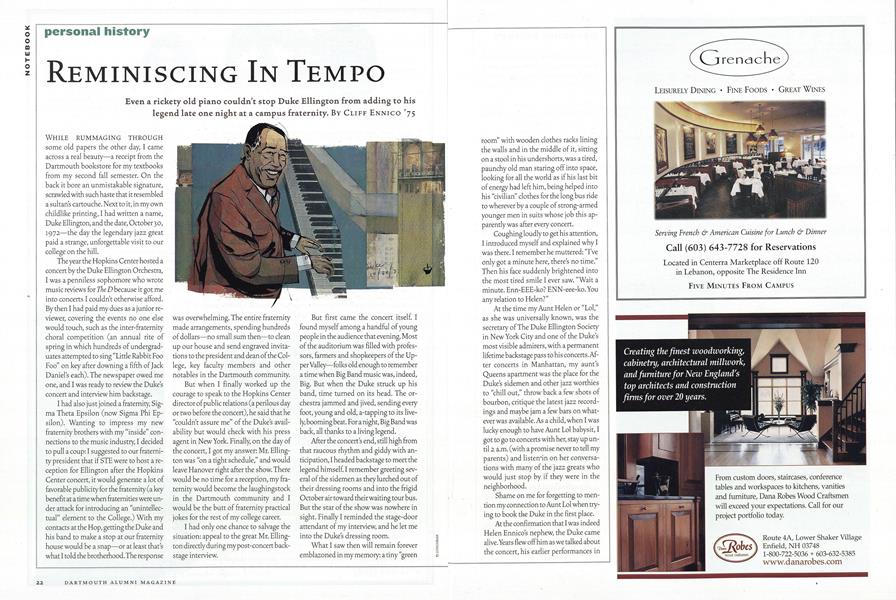

Reminiscing In Tempo

Even a rickety old piano couldn’t stop Duke Ellington from adding to his legend late one night at a campus fraternity.

May/June 2003 Cliff Ennico ’75Even a rickety old piano couldn’t stop Duke Ellington from adding to his legend late one night at a campus fraternity.

May/June 2003 Cliff Ennico ’75Even a rickety old piano couldn't stop Duke Ellington from adding to his legend late one night at a campus fraternity.

WHILE RUMMAGING THROUGH some old papers the other day, I came across a real beauty—a receipt from the Dartmouth bookstore for my textbooks from my second fall semester. On the back it bore an unmistakable signature, scrawled with such haste that it resembled a sultans cartouche. Next to it, in my own childlike printing, I had written a name, Duke Ellington, and the date, October 30, 1972—the day the legendary jazz great paid a strange, unforgettable visit to our college on the hill.

The year the Hopkins Center hosted a concert by the Duke Ellington Orchestra, I was a penniless sophomore who wrote music reviews for The D because it got me into concerts I couldn't otherwise afford. By then I had paid my dues as a junior reviewer, covering the events no one else would touch, such as the inter-fraternity choral competition (an annual rite of spring in which hundreds of undergraduates attempted to sing "Little Rabbit Foo Foo" on key after downing a fifth of Jack Daniel's each). The newspaper owed me one, and I was ready to review the Duke's concert and interview him backstage.

was overwhelming. The entire fraternity made arrangements, spending hundreds of dollars—no small sum then—to clean up our house and send engraved invitations to the president and dean of the College, key faculty members and other notables in the Dartmouth community. I had also just joined a fraternity, Sigma Theta Epsilon (now Sigma Phi Epsilon). Wanting to impress my new fraternity brothers with my "inside" connections to the music industry, I decided to pull a coup: I suggested to our fraternity president that if STE were to host a reception for Ellington after the Hopkins Center concert, it would generate a lot of favorable publicity for the fraternity (a key benefit at a time when fraternities were under attack for introducing an "unintellectual" element to the College.) With my contacts at the Hop, getting the Duke and his band to make a stop at our fraternity house would be a snap—or at least that's what I told the brotherhood. The response

But when I finally worked up the courage to speak to the Hopkins Center director of public relations (a perilous day or two before the concert), he said that he "couldn't assure me" of the Dukes availability but would check with his press agent in New York. Finally, on the day of the concert, I got my answer: Mr. Ellington was "on a tight schedule," and would leave Hanover right after the show. There would be no time for a reception, my fraternity would become the laughingstock in the Dartmouth community and I would be the butt of fraternity practical jokes for the rest of my college career.

I had only one chance to salvage the situation: appeal to the great Mr. Ellington directly during my post-concert backstage interview.

But first came the concert itself. I found myself among a handful of young people in the audience that evening. Most of the auditorium was filled with professors, farmers and shopkeepers of the Upper Valley—folks old enough to remember a time when Big Band music was, indeed, Big. But when the Duke struck up his band, time turned on its head. The orchestra jammed and jived, sending every foot, young and old, a-tapping to its lively, booming beat. For a night, Big Band was back, all thanks to a living legend.

After the concert's end, still high from that raucous rhythm and giddy with anticipation, I headed backstage to meet the legend himself. I remember greeting several of the sidemen as they lurched out of their dressing rooms and into the frigid October air toward their waiting tour bus. But the star of the show was nowhere in sight. Finally I reminded the stage-door attendant of my interview, and he let me into the Duke's dressing room.

What I saw then will remain forever emblazoned in my memory: a tiny "green room" with wooden clothes racks lining the walls and in the middle of it, sitting on a stool in his undershorts, was a tired, paunchy old man staring off into space, looking for all the world as if his last bit of energy had left him, being helped into his "civilian" clothes for the long bus ride to wherever by a couple of strong-armed younger men in suits whose job this apparently was after every concert.

Coughing loudly to get his attention, I introduced myself and explained why I was there. I remember he muttered: "I've only got a minute here, there's no time." Then his face suddenly brightened into the most tired smile I ever saw. "Wait a minute. Enn-EEE-ko? ENN-eee-ko.You any relation to Helen?"

At the time my Aunt Helen or "Lol," as she was universally known, was the secretary of The Duke Ellington Society in New York City and one of the Duke's most visible admirers, with a permanent lifetime backstage pass to his concerts. After concerts in Manhattan, my aunts Queens apartment was the place for the Dukes sidemen and other jazz worthies to "chill out," throw back a few shots of bourbon, critique the latest jazz recordings and maybe jam a few bars on what- ever was available. As a child, when I was lucky enough to have Aunt Lol babysit, I got to go to concerts with her, stay up until 2 a.m. (with a promise never to tell my parents) and listen in on her conversations with many of the jazz greats who would just stop by if they were in the neighborhood.

Shame on me for forgetting to mention my connection to Aunt Lol when trying to book the Duke in the first place.

At the confirmation that I was indeed Helen Ennico's nephew, the Duke came alive. Years flew off him as we talked about the concert, his earlier performances in the Dartmouth area and what it meant to be one of the last surviving swing men in the age of acid rock. Feeling the time was right, I explained my awkward situation: that at that very moment I had a fraternity house full of people and some very anxious brothers drinking scotch and waiting for a glimpse of the musical hero.

Over the objections of the two "clothes-men" cum body servants, whose job it was after all to keep the Great Man on schedule, the Duke agreed to put in a short appearance at my fraternity, provided he could stay in his traveling attire.

The next hour was a blur. Riding on the Duke's private bus with the two scowling bodyguards, who relented after I promised them free drinks (the Duke, himself, drank only seltzer—this was a working night for him). Hulling up in front of STE with a mob of students in the front yard and everyone—I mean everyonewho was anyone at Dartmouth waiting inside to meet The Man. Introducing Duke Ellington to the president, the dean, the chairman of the music department, the composer in residence, all the local news media and on and on and on, all as if he and I were old chums.

Then it happened.

In the reception room of STE there was a beat-up, rickety upright piano from the early part of last century. It was painted a ghastly maroon-brown. Nobodyused it except as a place to sit during fraternity board meetings. It had not been tuned or probably even played for more than 20 years. The insides had turned to rust, the result of countless glasses of beer and other liquids being poured down into them when someone needed to get rid of said liquids quickly. The entire machine was covered with two or three decades of dust, nicks and scratches.

The weary Duke Ellington cast his gaze on that piano, and lust grew in his eyes.

He walked up to it and, with amazing strength, thrust up the wooden key-cover. Dust flew everywhere, and when it cleared you could see what truly sorry shape the piano had taken. One of the keys was at a 45-degree angle to the horizontal. Most were painted alternately white and that hideous maroon-brown. Only half of the keys still had ivory on them; the rest were bare wood with visible splinters. It was the piano from Satan's whorehouse.

The Duke didn't seem to notice. He pulled out the piano bench, sat down at the keyboard and began playing "Satin Doll."

It was "Satin Doll" as I guarantee no one had ever heard it before or since. Only half the notes sounded. No two chords were in the same key. I could swear something living inside the piano started crawling around its interior, providing its own percussive beat. Then the Duke started to sing. But he could not compensate for that dreadful, cacophonous sound. It was "Satin Doll" as interpreted by a punk rock ensemble on Ecstasy.

Arespectful but awkward silence filled the room. Many smiled, but no one laughed. No one dared. This was a sacred moment—a unique live performance by an American music legend. Only his hosts had let him down, providing him a piano unfit for a child, let alone a legend. The president of our fraternity, looking as if he was about to have a seizure, grabbed my arm, dug his nails into my flesh and whispered in my ear: "Please...get...him... to...stop."

Get Duke Ellington to stop playing the piano.

Yeah. Right.

I walked up to the great man as modestly as I could and stood by the side of the piano bench, waiting for the right moment to apologize. But the Duke just hammered away at the keys, trying frantically to make that wretched instrument yield "Satin Doll." I had no idea what to say. The situation was beyond salvation. Or so I thought.

Because then Duke Ellington—one of the greatest musicians to ever grace the planet—looked up at me with tears in his eyes, flashed the widest toothy grin this side of Wonderland and, with a private wink, bellowed in a stage whisper that could have been heard throughout the White Mountains: "Don't worry, man, we've got 'em all fooled. They think it's the piano!"

CLIFF ENNICO is the host of Money Hunt on PBS television. He lives in Connecticut.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Affirming Flame

May | June 2003 By SUSAN DENTZER ’77 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDoes Your Major Matter?

May | June 2003 By Lisa Furlong -

Feature

FeatureWhy an Engineer Needs English Lit

May | June 2003 By SAMUEL C. FLORMAN ’46, TH’46 -

Artifact

ArtifactPhil’s Favorites

May | June 2003 By Phil Cronenwett -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Global Classroom

May | June 2003 By Jack Shepherd -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2003 By MIKE MAHQNEY '92

Personal History

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYAristotle on the A-Train

Nov/Dec 2007 By Alexander Nazaryan ’02 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBag of Tricks

May/June 2005 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOut Of The Woods

Nov/Dec 2000 By J. Mark Riddell ’90 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYMutual Transformation

Mar/Apr 2007 By Joanne A. Herman ’75 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryOut of Bounds

May/June 2002 By Sarah Lang Sponheim ’79 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLearning Experience

July/August 2008 By Susan Marine