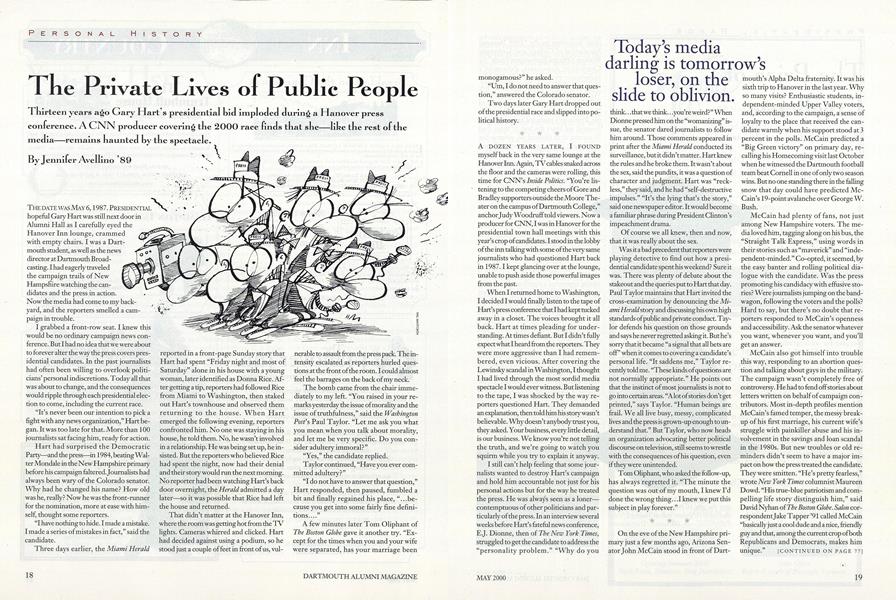

The Private Lives of Public People

Thirteen years ago Gary Hart’s presidential bid imploded during a Hanover press conference. A CNN producer covering the 2000 race finds that she—like the rest of the media—remains haunted by the spectacle.

MAY 2000 Jennifer Avellino ’89Thirteen years ago Gary Hart’s presidential bid imploded during a Hanover press conference. A CNN producer covering the 2000 race finds that she—like the rest of the media—remains haunted by the spectacle.

MAY 2000 Jennifer Avellino ’89Thirteen years ago Gary Hart's presidential bid imploded during a Hanover press conference. A CNN producer covering ike 2000 race finds thai she—like the rest of the media-remains haunted by the spectacle.

THE DATE WAS MAY 6,1987. hopeful Gary Hart was still next door in Alumni Hall as I carefully eyed the Hanover Inn lounge, crammed with empty chairs. I was a Dartmouth student, as well as the news director at Dartmouth Broadcasting. I had eagerly traveled the campaign trails of New Hampshire watching the candidates and the press in action Now the media had come to my backyard, and the reporters smelled a campaign in trouble.

I grabbed a front-row seat. I knew this would be no ordinary campaign news conference. But I had no idea that we were about to forever alter the way the press covers presidential candidates. In the past journalists had often been willing to overlook politicians' personal indiscretions. Today all that was about to change, and the consequences would ripple through each presidential election to come, including the current race.

"It's never been our intention to pick a fight with any news organization," Hart began. It was too late for that. More than 100 journalists sat facing him, ready for action.

Hart had surprised the Democratic Party—and the press—in 1984, beating Walter Mondale in the New Hampshire primary before his campaign faltered. Journalists had always been wary of the Colorado senator. Why had he changed his name? How old was he, really? Now he was the front-runner for the nomination, more at ease with himself, thought some reporters.

"I have nothing to hide. I made a mistake. I made a series of mistakes in fact," said the candidate.

Three days earlier, the Miami Herald reported in a front-page Sunday story that Hart had spent "Friday night and most of Saturday" alone in his house with a young woman, later identified as Donna Rice. After getting a tip, reporters had followed Rice from Miami to Washington, then staked out Hart's town house and observed them returning to the house. When Hart emerged the following evening, reporters confronted him. No one was staying in his house, he told them. No, he wasn't involved in a relationship. He was being set up, he insisted. But the reporters who believed Rice had spent the night, now had their denial and their story would run the next morning. No reporter had been watching Hart's back door overnight, the Herald admitted a day later—so it was possible that Rice had left the house and returned.

That didn't matter at the Hanover Inn, where the room was getting hot from the TV lights. Cameras whirred and clicked. Hart had decided against using a podium, so he stood just a couple of feet in front of us, vulnerable to assault from the press pack. The intensity escalated as reporters hurled questions at the front of the room. I could almost feel the barrages on the back of my neck.

The bomb came from the chair immediately to my left. "You raised in your remarks yesterday the issue of morality and the issue of truthfulness," said the WashingtonPost's Paul Taylor. "Let me ask you what you mean when you talk about morality, and let me be very specific. Do you consider adultery immoral? "

"Yes," the candidate replied.

Taylor continued, "Have you ever committed adultery?"

"I do not have to answer that question," Hart responded, then paused, fumbled a bit and finally regained his place, "...because you get into some fairly fine definitions...."

A few minutes later Tom Oliphant of The Boston Globe gave it another try. "Except for the times when you and your wife were separated, has your marriage been monogamous?" he asked.

"Um, I do not need to answer that question," answered the Colorado senator.

Two days later Gary Hart dropped out of the presidential race and slipped into political history.

A DOZEN YEARS LATER, I FOUND myself back in the very same lounge at the Hanover Inn. Again, TV cables snaked across the floor and the cameras were rolling, this time for CNN's Inside Politics. "You're listening to the competing cheers of Gore and Bradley supporters outside the Moore Theater on the campus of Dartmouth College," anchor Judy Woodruff told viewers. Now a producer for CNN, I was in Hanover for the presidential town hall meetings with this year's crop of candidates. I stood in the lobby of the inn talking with some of the very same journalists who had questioned Hart back in 1987.I kept glancing over at the lounge, unable to push aside those powerful images from the past.

When I returned home to Washington, I decided I would finally listen to the tape of Hart's press conference that I had kept tucked away in a closet. The voices brought it all back. Hart at times pleading for understanding. At times defiant. But I didn't fully expect what I heard from die reporters. They were more aggressive than I had remembered, even vicious. After covering the Lewinsky scandal in Washington, I thought I had lived through the most sordid media spectacle I would ever witness. But listening to the tape, I was shocked by the way reporters questioned Hart. They demanded an explanation, then told him his story wasn't believable. Why doesn't anybody trust you, they asked. Your business, every little detail, is our business. We know you're not telling the truth, and we're going to watch you squirm while you try to explain it anyway.

I still can't help feeling that some journalists wanted to destroy Hart's campaign and hold him accountable not just for his personal actions but for the way he treated the press. He was always seen as a lonercontemptuous of other politicians and particularly of the press. In an interview several weeks before Hart's fateful news conference, E.J. Dionne, then of The New York Times, struggled to get the candidate to address the "personality problem." "Why do you think.. .that we think.. .you're weird?" When Dionne pressed him on the "womanizing" issue, the senator dared journalists to follow him around. Those comments appeared in print after the Miami Herald conducted its surveillance, but it didn't matter. Hart knew the rules and he broke them. It wasn't about the sex, said the pundits, it was a question of character and judgment. Hart was "reckless, " they said, and he had "self-destructive impulses." "It's the lying that's the story," said one newspaper editor. It would become a familiar phrase during President Clinton's impeachment drama.

Of course we all knew, then and now, that it was really about the sex.

Was it a bad precedent that reporters were playing detective to find out how a presidential candidate spent his weekend? Sure it was. There was plenty of debate about the stakeout and the queries put to Hart that day. Paul Taylor maintains that Hart invited the cross-examination by denouncing the Miami Herald story and discussing his own high standards of public and private conduct. Taylor defends his question on those grounds and says he never regretted asking it. But he's sorry that it became "a signal that all bets are off' when it comes to covering a candidate's personal life. "It saddens me," Taylor recendy told me. "These kinds of questions are not normally appropriate." He points out that the instinct of most journalists is not to go into certain areas. "A lot of stories don't get printed," says Taylor. "Human beings are frail. We all live busy, messy, complicated lives and the press is grown-up enough to understand that." But Taylor, who now heads an organization advocating better political discourse on television, still seems to wrestle with the consequences of his question, even if they were unintended.

Tom Oliphant, who asked the follow-up, has always regretted it. "The minute the question was out of my mouth, I knew I'd done the wrong thing.. .I knew we put this subject in play forever."

On the eve of the New Hampshire primary just a few months ago, Arizona Senator John McCain stood in front of Dartmouth's Alpha Delta fraternity. It was his sixth trip to Hanover in the last year. Why so many visits? Enthusiastic students, independent-minded Upper Valley voters, and, according to the campaign, a sense of loyalty to the place that received the candidate warmly when his support stood at 3 percent in the polls. McCain predicted a "Big Green victory" on primary day, recalling his Homecoming visit last October when he witnessed the Dartmouth football team beat Cornell in one of only two season wins. But no one standing there in the falling snow that day could have predicted McCain's 19-point avalanche over George W. Bush.

McCain had plenty of fans, not just among New Hampshire voters. The media loved him, tagging along on his bus, the "Straight Talk Express," using words in their stories such as "maverick" and "independent-minded." Co-opted, it seemed, by the easy banter and rolling political dialogue with the candidate. Was the press promoting his candidacy with effusive stories? Were journalists jumping on the bandwagon, following the voters and the polls? Hard to say, but there's no doubt that reporters responded to McCain's openness and accessibility. Ask the senator whatever you want, whenever you want, and you'll get an answer.

McCain also got himself into trouble this way, responding to an abortion question and talking about gays in the military. The campaign wasn't completely free of controversy. He had to fend off stories about letters written on behalf of campaign contributors. Most in-depth profiles mention McCain's famed temper, the messy breakup of his first marriage, his current wife's struggle with painkiller abuse and his involvement in the savings and loan scandal in the 1980s. But new troubles or old reminders didn't seem to have a major impact on how the press treated the candidate. They were smitten. "He's pretty fearless," wrote New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd. "His true-blue patriotism and compelling life story distinguish him," said David Nyhan of The Boston Globe. Salon correspondent Jake Tapper '91 called McCain "basically just a cool dude and a nice, friendly guy and that, among the current crop of both Republicans and Democrats, makes him unique."

McCain, in short, had everything Hart didn't—a winning way with the press corps and a willingness to admit his faults, whether it concerned his personal failings or his campaign tactics. Tapper asked McCain in New Hampshire if he'd violated his pledge not to go negative when he questioned whether George W. Bush was "ready for prime time."

"It certainly approaches it," a grinning McCain acknowledged to Tapper, who described the senator as "charming the two dozen or so reporters hanging on his every word."

Journalists, like the voters, saw something special in McCain. He wasn't just a maverick, he was a true hero, a Silver Star winner who'd faced much tougher odds during his days as a prisoner of war in Vietnam. We didn't have heroes in American life anymore, did we? Those we had, like Colin Powell, certainly weren't running for political office.

Many of us in the media also felt something else. McCain wasn't Clinton, whose stupidity put us through a year of late nights and long weekends at the office. The guy who made us go on television and turn our newscasts into X-rated recitations of his most intimate moments with Monica Lewinsky. The public hated us for it. It was his fault that we'd all been dragged through the proverbial mud.

So, have the media been reformed—are we willing to junk our obsession with scandal? Will future John McCains get an easy ride?

Don't bet on it.

Are we remorseful over coverage of the president's impeachment or the destruction of politicians like Gary Hart?

Don't bet on that either.

The "media" these days are everything from the cable chat shows, to The New YorkTimes, to an individual with a computer and a Web site. We all have widely different standards, at least on the surface. Respectable news organizations often resist a negative story at first, then end up covering it because "it's out there" on talk radio, on the Internet, in the tabloids. Today's media darling is tomorrow's loser, on the slide to oblivion. And, more than anything, we're a fickle bunch. We follow the polls, we follow each other and we still can't resist a good story about a candidate in trouble.

Today's media darling is tomorrow's loser, on the slide to oblivion.

JENNIFER AVELLINO is the senior producer ofCNN's media criticism program, Reliable Sources.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

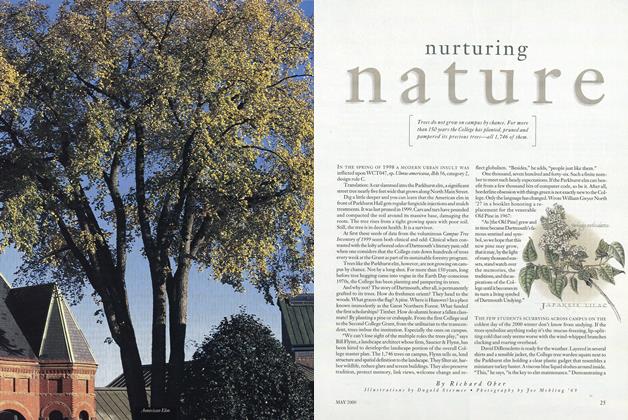

Cover StoryNurturing Nature

May 2000 By Richard Ober -

Feature

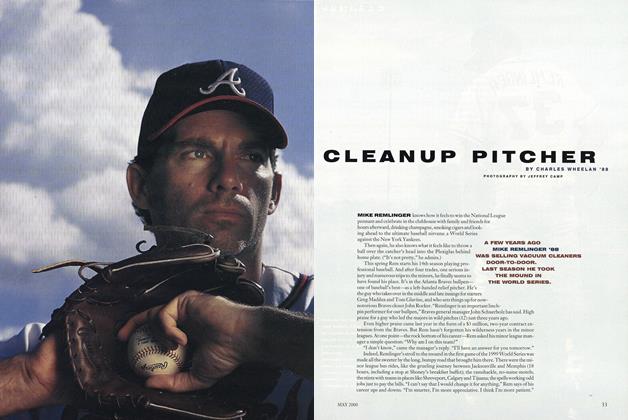

FeatureCleanup Pitcher

May 2000 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureLive From New York!

May 2000 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

SYLLABUS

SYLLABUSScreening Reality

May 2000 By Kathleen Burge ’89 -

Article

ArticleThe Price of Excellence

May 2000 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleYou Are Here

May 2000 By Noel Perrin

Jennifer Avellino ’89

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYReunited

MAY | JUNE 2016 By DAISY ALPERT FLORIN ’95 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Pursuit of Happiness

May/June 2007 By Daniel Becker ’84 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryAwakening

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By JOE GLEASON ’77, JOE GLEASON ’77 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGolden Girl

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By JUDITH GREENBERG ’88 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYWhat is Perfect?

Sept/Oct 2000 By Mary Cleary Kiely ’79 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYMistaken Identity

NovembeR | decembeR By SUZANNE SPENCER RENDAHL ’93