The Allure of Beauty

Professor Bill Ballard’s scientific know-how brought a rare orchid back from the brink.

May/June 2003 Henry Homeyer ’68Professor Bill Ballard’s scientific know-how brought a rare orchid back from the brink.

May/June 2003 Henry Homeyer ’68Professor Bill Ballard's scientific know-how brought a rare orchid back from the brink.

DECADES BEFORE SUSAN ORLEAN'S bestselling The Orchid Thief explored the nature of passion, the late professor Bill Ballard '28 expressed his passion for nature—and orchids—in a distinctly different way. The professor didn't steal rare, wild orchids and introduce them to a life of domesticity. Instead he channeled his skills as a scientific researcher toward devising a way to grow the elusive beauties in a greenhouse and reintroduce them into the wild.

Ballard's appreciation of the orchid began at the age of 12 when, walking in the woods near his home in Greenfield, Massachusetts, he came upon a stand of orchids in full bloom. Overwhelmed with their beauty, "I fell to my knees and wept," Ballard recalled years later.

Years passed before Ballard would be reunited with the flowers in such a profound way. He went on to graduate Phi Beta Kappa from Dartmouth, served as a biology instructor at the College from 1930 to 1935 and earned a doctorate from Yale in 1933. In 1935 he was promoted to assistant professor in the Colleges zoology department. As an expert on fish embryology, Ballard became one of the Colleges top researchers, garnering a $39,000 National Science Foundation grant in 1961 to study cell movements in developing fish embryos.

Meanwhile, the objects of his early affection —the orchids—were not faring nearly as well. The combination of habitat destruction and poaching was has- tening the disappearance of the alreadyelusive plant.

Upon his retirement in 1971, Ballard returned to the same Massachusetts swamps he had explored as a youth. When he couldn't find any of the flowers, he embarked upon an ambitious mission: the restoration of the rare lady's slipper or- chids in his native New England.

At first Ballard tried to increase the odds that orchids would thrive in the wild. To do that he had to encourage the flowers to develop seeds. Armed with a box of toothpicks, he would visit Upper Valley wetlands each June, painstakingly collecting the pollen from one lady's slipper and then delivering it to another. His pollination method proved more effective than natures: While only the most determined bees—10 percent—are able to make theirway through the blooms small opening to the stamen, Ballard and his toothpicks achieved a 90 percent pollination rate.

Later in the fall Ballard would return to the swamp and harvest lady's slipper seeds for use in the next phase of his great orchid challenge: propagating a plant indoors from seed.

Growing orchids isn't as simple as sticking some seeds into the ground. Ballard once estimated that he sowed some 5 million orchid seeds on a College-owned wetland without a single plant sprouting. Unlike most flowers, the lady's slipper makes seeds without a cover containing food to nourish the young embryo. Rather, the embryos are nourished for two to three years by a symbiotic fungus. Other researchers had thought that the fungus wasn't compatible with laboratory conditions, so they assumed that growing orchids in a laboratory was impossible. Ballard, who worked in his Dartmouth lab well beyond retirement, found he could germinate and grow the fungus in a sterile medium similar to that used for growing bacteria. That discovery allowed him to grow lady's slipper plants from the seeds he collected.

After a decade of experimenting, Ballard published a paper in the late 1980s that described his success at coaxing the white-and-rose-colored bloom of the showy lady's slipper from seed. But there was more to Ballard's method than simply discovering a means of growing an orchid indoors and publishing a paper about it. He wanted to involve other people.

"This world was made beautiful," Ballard once told a newspaper reporter. "But it's being made less beautiful by people who don't understand the importance of beauty."

When Ballard successfully propagated the showy lady's slipper, its introduction to Schmidt Bog in his hometown of Norwich, Vermont, became a commmunity effort. While Ballard wanted people to love his orchids as much as he did, he was wary of the plants being loved to death. Ballard coaxed townspeople into hauling in planks and eventually building a boardwalk to provide access through the rough terrain while protecting the delicate plants. And to make it a little more difficult for unsupervised visitors to find the plants, Ballard often brought folks on a circuitous route to the bog, which is only a few yards off a town road. Ballard wanted the bog to stay wild, and it has. Today a corps of volunteers, many of whom originally worked with Ballard, care for the orchids, removing invasive exotics such as buckthorn that threaten to overshadow the flowers and Ballard's legacy.

Although Ballard died in 1998 at the age of 92, his spirit lives on through the lady's slippers he introduced in the wild and through the community willing to nurture and protect them. Ballard spent the final summer of his life distributing plants to all who would care for them and enjoying one last season of blooms. Despite a debilitating battle with prostate cancer, he held on for months longer than the doctors predicted. In his final days, while sitting outside in his wheelchair, Ballard turned to one of his daughters. "It's over now," he said. "All my flowers have bloomed." Two weeks later he died.

Bee-plus; Ballard's pollination techniquesachieved a 90 percent success rate.

HENRY HOMEYER is a freelance writer andprofessional garden designer living in CornishFlat, New Hampshire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Affirming Flame

May | June 2003 By SUSAN DENTZER ’77 -

Cover Story

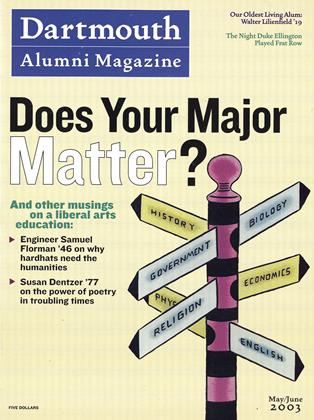

Cover StoryDoes Your Major Matter?

May | June 2003 By Lisa Furlong -

Feature

FeatureWhy an Engineer Needs English Lit

May | June 2003 By SAMUEL C. FLORMAN ’46, TH’46 -

Artifact

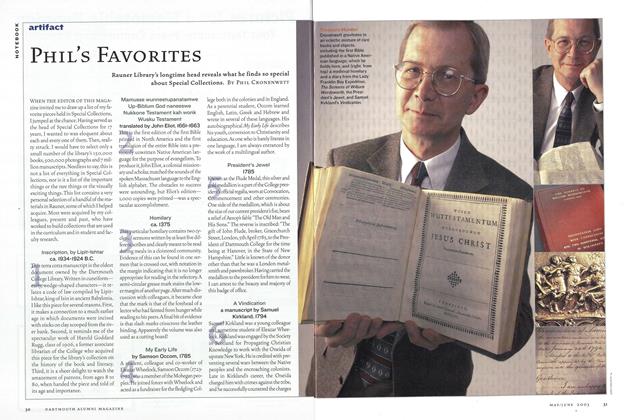

ArtifactPhil’s Favorites

May | June 2003 By Phil Cronenwett -

Personal History

Personal HistoryReminiscing In Tempo

May | June 2003 By Cliff Ennico ’75 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Global Classroom

May | June 2003 By Jack Shepherd

OUTSIDE

-

OUTSIDE

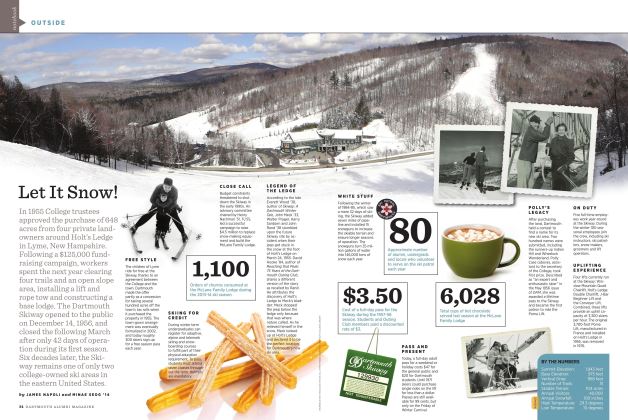

OUTSIDELet It Snow!

JAnuAry | FebruAry -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEHarvard Leads the Way

Jan/Feb 2005 By Bryant Urstadt '91 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEDog Day Afternoons

Nov/Dec 2005 By LISA DENSMORE ’83 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEAre You a Chubber?

Jan/Feb 2007 By Lisa Densmore ’83 -

Outside

OutsideGetting the Ax

Sept/Oct 2003 By Lisa Gosseling -

OUTSIDE

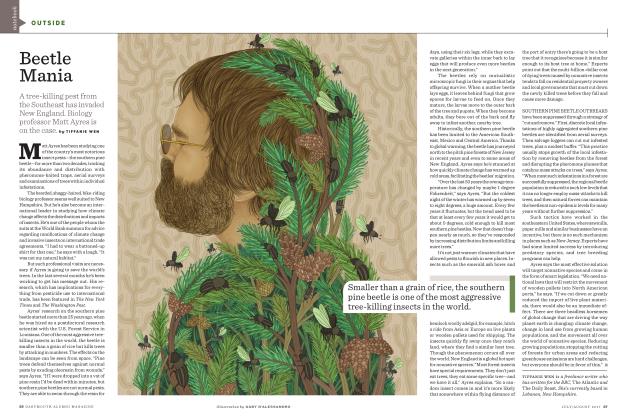

OUTSIDEBeetle Mania

JULY | AUGUST 2017 By TIFFANIE WEN